Scraper reduction at the Early Neolithic site of Hurst Fen, Suffolk, England

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.2218/jls.9629Palabras clave:

Hurst Fen; scraper; reduction intensity; typology; Early Neolithic; Grahame ClarkResumen

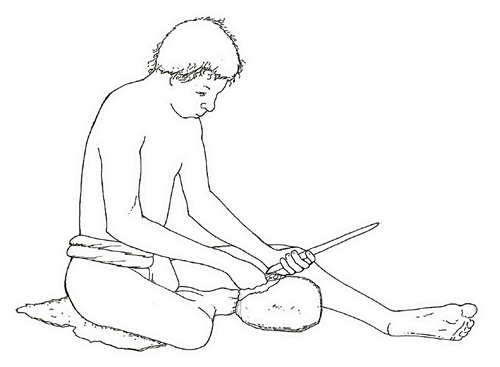

Prior analyses of Neolithic flaked stone assemblages in Britain have tended to focus on the relative abundance of different implement types as a basis for inferring the structure of settlement and subsistence patterns during this period, with dorsally retouched ‘scrapers’ dominating the retouched components of most assemblages. Here we investigate the relationship between scraper morphology and reduction intensity at the classic Early Neolithic site of Hurst Fen in Suffolk, England. We hypothesize that the morphological variability underpinning the distinction between formal scraper types at Hurst Fen is largely a product of increasing reduction intensity. To test this hypothesis, we apply a range of quantitative measures of reduction intensity to a sample of 175 complete scrapers from the site, including: Kuhn’s (1990) Geometric Index of Unifacial Reduction (GIUR), Hiscock and Attenbrow's (2002; 2005) retouch curvature and retouched zone indices, perimeter of retouch, and retouched edge angle. Correlation statistics and descriptive plots of the relationship between Kuhn’s GIUR and the remaining retouch characteristics reveal universally positive and statistically significant relationships, albeit with the correlation between the GIUR and retouched edge angle markedly weaker than for the other retouch characteristics. Collectively, the results of our analyses support the hypothesis that the extent to which scrapers were reduced throughout their respective use-lives was a critical factor in the creation of morphological and, by extension, typological variability in the Hurst Fen scraper assemblage. At the same time, our data suggest that Early Neolithic knappers at Hurst Fen habitually knapped and resharpened scrapers in such a manner that a relatively low edge angle of around 60˚ was continually reproduced, raising the possibility of preconceived ‘designs’ that were primarily expressed in the morphological features of retouched edges. We propose a model of scraper reduction that accounts for most of the differences in scraper morphology at Hurst Fen and evaluate the analytical utility of Clark’s hugely influential typological scheme in view of this. We also consider the implications of our findings for interpretations of morphological patterning in British Neolithic scraper assemblages more broadly.

Referencias

Andrefsky, W. 2006, Experimental and archaeological verification of an index of retouch for hafted bifaces. American Antiquity, 71: 743-758. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/40035887

Andrefsky, W. 1994, Raw-material availability and the organization of technology. American Antiquity, 59(1): 21-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3085499

Ballin, T. B. 2021, Classification of lithic artefacts from the British Late Glacial and Holocene periods. Archaeopress, Oxford, 87 p.

Bamforth, D. B. 1986, Technological efficiency and tool curation. American Antiquity, 51: 38-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/280392

Bamforth, D. B., & Bleed, P. 1997, Technology, flaked stone technology, and risk. In: Rediscovering Darwin: evolutionary theory and archaeological explanation (C.M. Barton, C.M. & Clark, G. A, Eds.), Archaeological papers of American Anthropological Association Vol. 7, American Anthropological Association, Arlington: p. 109-139.

Barton, C. M. 1990, Beyond style and function: a view from the Middle Paleo-lithic. American Anthropologist, 92: 57-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1990.92.1.02a00040

Beadsmore, E. 2006, Earlier Neolithic flint. In: Excavations at Kilverstone, Norfolk: an episodic landscape history (Garrow, D., Lucy, S. & Knight, M., Eds), Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Cambridge: p. 53-70.

Bischoff, R.J. 2023, Geometric morphometric analysis of projectile points from the southwest United States. Peer Community Journal, 3: e80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.archaeo.100315

Binford, L. R. 1973, Interassemblage variability: the Mousterian and the “functional argument.” In: The explanation of cultural change: models in prehistory (Renfrew, C., Ed.), Duckworth, London: p. 227-254.

Binford, L. R., & Binford, S. R. 1966, A preliminary analysis of functional variability in the Mousterian of Levallois facies, American Anthropologist, 68: 238-295. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1966.68.2.02a001030

Bisson, M. S. 2000, Nineteenth century tools for twenty-first century archaeology? Why the Middle Paleolithic typology of Francois Bordes must be replaced, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 7:1-48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009578011590

Blades, B. S. 2003, End scraper reduction and hunter-gatherer mobility. American Antiquity, 68(1): 141-156. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3557037

Bleed, P. 1986, The optimal design of hunting weapons: maintainability or reliability. American Antiquity, 51: 737-747. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/281295

Bordes, F. 1961a, Mousterian cultures in France, Science, 134: 803-810. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.134.3473.803

Bordes, F. 1961b, Typologie du Paléolithique ancien et moyen. Publications de L’In-stitut de Préhistorie de L’Université de Bordeaux; Mémoire Vol. 1. Imprimeries Delmas, Bordeaux, 85 p. (in French) ("Typology of the Early and Middle Palaeolithic")

Bordes, F., & de Sonneville-Bordes, D. 1970, The significance of variability in Palaeolithic assemblages, World Archaeology, 2: 61-73. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1970.9979400

Bousman, C. 1993, Hunter-gatherer adaptions, economic risk and tool design, Lithic Technology, 12: 59-96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01977261.1993.11720897

Bousman, C. 2005, Coping with risk: Later Stone Age technological strategies at Blydefontein rock shelter, South Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 24: 193-226. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2005.01.001

Briscoe, G. 1954, A Windmill Hill site at Hurst Fen Mildenhall. Proceedings of the Cambridge Antiquarian Society, 47: 13-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5284/1072900

Brown, A. G. 1995, Beyond Stone Age economics: a strategy for a contextual lithic analysis. In: Lithics in context: suggestions for the future direction of lithic studies, (Schofield, A.J., Ed.), Lithic Studies Society Occasional Paper Vol. 5. Lithic Studies Society, London: p. 27-36.

Brumm, A., & McLaren, A. P. 2011, Scraper reduction and “imposed form” at the Lower Palaeolithic site of High Lodge, England. Journal of Human Evolution, 60(2), 185-204. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.10.006

Bustos-Pérez, G., & Baena, J. 2019, Exploring volume lost in retouched artifacts using height of retouch and length of retouched edge. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 27: 101922. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.101922

Bustos-Pérez, G., Gravina, B., Brenet, M. & Romagnoli, F. 2024, The contribution of 2D and 3D geometric morphometrics to lithic taxonomies: testing discrete categories of backed flakes from recurrent centripetal core reduction. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, 7(5). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-023-00167-7

Butler, C. 2005, Prehistoric flintwork. Tempus, Stroud, 223 p.

Clark, J. G. D. 1932, The Mesolithic Age in Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 222 p.

Clark, J. G. D., Higgs, E., & Longworth, I. 1960, Excavations at the Neolithic site at Hurst Fen, Mildenhall, Suffolk (1954, 1957 and 1958), Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 26: 202-245. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00016315

Clarkson, C. 2002a, An Index of invasiveness for the measurement of unifacial and bifacial retouch: A theoretical, experimental and archaeological verification. Journal of Archaeological Science, 29(1): 65-75. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2001.0712

Clarkson, C. 2002b, Holocene scraper reduction, technological organization and landuse at Ingaladdi rockshelter, northern Australia. Archaeology in Oceania, 37(2): 79-86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4453.2002.tb00508.x

Clarkson, C. 2005, Tenuous types: scraper reduction continuums in the eastern Victoria River region, Northern Territory. In: Lithics “Down Under”: Australian approaches to lithic reduction, use and classification (Clarkson, C. & Lamb, L., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1408. Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 21-33.

Clarkson, C. 2006, Explaining point variability in the Eastern Victoria River Region, Northern Territory. Archaeology in Oceania, 41(3): 97-106. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4453.2006.tb00632.x

Clarkson, C. 2007, Lithics in the land of the Lightning Brothers: The archaeology of Wardaman Country, Northern Territory. Terra Australis Vol. 25. ANU Press, Canberra, 221 p.

Clarkson, C. 2008, Changing reduction intensity, settlement, and subsistence in Wardaman Country, Northern Australia. In: Lithic technology: measures of production, use, and curation (Andrefsky, W, Ed.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: p. 286-316.

Cotterell, B., & Kamminga, J. 1987, The formation of flakes. American Antiquity, 52(4): 675-708. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/281378

Cummings, V. 2017, The Neolithic of Britain and Ireland. Routledge, London, 295 p.

Dibble, H. L. 1984. Interpreting typological variation of Middle Paleolithic scrapers: function, style, or sequence of reduction? Journal of Field Archaeology, 11: 431-436. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1179/009346984791504526

Dibble, H. L. 1987a, Reduction sequences in the manufacture of Mousterian implements of France. In: The Pleistocene Old World: regional perspectives (Soffer, O., Ed.). Plenum Press, New York: p. 33-45.

Dibble, H. L. 1987b, The Interpretation of Middle Paleolithic scraper morphology. American Antiquity, 52(1): 109-117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/281062

Dibble, H. L. 1989, The implications of stone tool types for the presence of language during the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic. In: The human revolution: behavioural and biological perspectives on the origins of modern humans (Mellars, P. & Stringer, C.. Eds.). Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh: p. 415-432.

Dibble, H. L. 1991a, Local raw material exploitation and its effects on Lower and Middle Paleolithic assemblage variability. In: Raw material economies among prehistoric hunter-gatherers (Montet-White, A. & Holen, S., Eds). University of Kansas Press, Lawrence: p. 33-47

Dibble, H. L. 1991b, Mousterian assemblage variability on an interregional scale. Journal of Anthropological Research, 47(2): 239-257. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3630327

Dibble, H. L. 1995, Middle Paleolithic scraper reduction: background, clarification, and review of the evidence to date. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, 2(4): 299-368. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02229003

Dibble, H. L., & Rolland, N. 1992, On assemblage variability in the Middle Paleolithic of western Europe. In: The Middle Paleolithic: adaptation, behavior, and variability (Dibble, H.L. & Mellars, P., Eds). University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia: p. 1-28.

Douze, K., & Delagnes, A. 2016, The pattern of emergence of a Middle Stone Age tradition at Gademotta and Kulkuletti (Ethiopia) through convergent tool and point technologies. Journal of Human Evolution, 91: 93-121. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.11.006

Fagan, B. 2001, Grahame Clark: An intellectual biography of an archaeologist. Westview Press, Boulder, 304 p.

Garrow, D., Beadsmore, E., & Knight, M. 2005, Pits clusters and the temporality of occupation: An earlier Neolithic Site at Kilverstone, Thetford, Norfolk. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 71: 139-157. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00000980

Garrow, D., Lucy, S., & Gibson, D. (Eds) 2006, Excavations at Kilverstone, Norfolk: An Episodic landscape history. East Anglian Archaeology Vol. 113. Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Cambridge, 257 p.

Graf, K. 2010, Hunter-gatherer dispersals in the mammoth-steppe: technological provisioning and land-use in the Enisei River Valley, South-Central Siberia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 37: 210-223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2009.09.034

Harding, P. 2017, Excavations of Reydon Farm: Early Neolithic pit digging in East Suffolk. Proceedings of the Suffolk Institute of Archaeology & History, 44(1): 1-18. URL: https://suffolkinstitute.pdfsrv.co.uk/customers/Suffolk%20Institute/2021/07/30/wetransfer-024246/SIAH%202017%20002%20Reydon%20Farm.pdf

Hashemi, S.M., Nasab, H.V., Berillon, G. & Oryat, M. 2021, An investigation of the flake-based lithic tool morphology using 3D geometric morphometrics: A case study from the Mirak Paleolithic Site, Iran. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 37(June): 102948. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2021.102948

Hayden, B. 1977, Stone tool functions in the Western Desert. In: Stone tools as cultural markers (Wright, R.V.S., Ed.). Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra: p. 178-188.

Healy, F. (Ed) 1988, Spong Hill part VI: 7th to 2nd millennia BC. East Anglian Archaeology Vol. 39. The Norfolk Archaeological Unit, Dereham, 118 p.

Healy, F. 2013, In the Shadow of hindsight: pre-Iron Age Spong Hill viewed from 2010. In Spong Hill, Part IX: Chronology and Synthesis (Hills, C. & Lucy, S., Eds.). McDonald Institute, Cambridge: p. 12-26

Hiscock, P., & Attenbrow, V. (2002). Morphological and reduction continuums in eastern Australia: measurement and implications at Capertee 3. In: Barriers, borders, boundaries: proceedings of the 2001 Australian Archaeological Association annual conference (Ulm, S., Westcott, C., Reid, J., Ross, A., Lilley, I., Prangnell, J. & Kirkwood, L., Eds.), Tempus Vol. 7. Anthropology Museum, University of Queensland, Brisbane: p. 167-174.

Hiscock, P., & Attenbrow, V. 2003, Early Australian implement variation: A reduction model. Journal of Archaeological Science, 30(2): 239-249. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2002.0830

Hiscock, P., & Attenbrow, V. 2005, Australia’s Eastern Regional Sequence revisited: technology and change at Capertee 3, BAR International Series Vol. 1397. Archaeopress, Oxford, 151 p

Hiscock, P., & Attenbrow, V. 2011, Technology and technological change in eastern Australia: the example of Capertee 3. In: Keeping your edge: recent approaches to the organisation of stone artefact technology (Marwick, B. & Mackay, A., Eds), BAR International Series Vol. 2273. Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 21-32.

Hiscock, P., & Clarkson, C. 2005a, Measuring artefact reduction - an examination of Kuhn’s Geometric Index of Reduction. In: Lithics “Down Under”: Australian approaches to lithic reduction, use and classification (Clarkson, C. & Lamb, L., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1408. Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 7-20.

Hiscock, P., & Clarkson, C. 2005b, Experimental evaluation of Kuhn’s Geometric Index of Reduction and the flat-flake problem. Journal of Archaeological Science, 32(7): 1015-1022. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2005.02.002

Hiscock, P., & Clarkson, C. 2008, The construction of morphological diversity: a study of Mousterian implement retouching at Combe Grenal. In: Lithic technology: measures of production, use, and curation (Andrefsky, W, Ed.). Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: p. 106-135.

Hiscock, P., & Clarkson, C. 2015, Retouch intensity on Quina scrapers at Combe Grenal: a test of the reduction model. In Taxonomic tapestries: the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research (Behie, A. M. & Oxenham, M. F., Eds.). ANU Press, Canberra: p. 103-128.

Holdaway, S., McPherron, S., & Roth, B. 1996, Notched tool reuse and raw material availability in French Middle Paleolithic sites. American Antiquity, 61(2): 377-387. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/282432

Hummler, M. 2005, Before Sutton Hoo: the prehistoric settlement (c.3000 BC to c.AD 550). In: Sutton Hoo: a seventh-century princely burial ground and its context (Carver, M., Ed.). British Museum Press, London: p. 391-458.

Jeske, R. J. 1992, Energetic efficiency and lithic technology: an Upper Mississippian example. American Antiquity, 57(2): 467-481. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600054366

Kuhn, S. 1992, On planning and curated technologies in the Middle Paleolithic. Journal of Anthropological Research, 48: 185-214. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3630634

Kuhn, S. 1994, A formal approach to the design and assembly of mobile toolkits. American Antiquity, 59(3): 426-442. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/282456

Kuhn, S. 1995, Mousterian lithic technology: an ecological perspective. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 209 p.

Kuhn, S. 2004, Upper Paleolithic raw material economies at Ucagizli Cave, Turkey. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 23: 431-448. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2004.09.001

Lerner, H. 2015, Dynamic variables and the use-related reduction of Southern Huon projectile points. In: Works in stone: contemporary perspectives on lithic analysis (Shott, M., Ed.) The University of Utah Press Salt Lake City: p. 143-161.

Lombao, D., Cueva-Temprana, A., Mosquera, M., & Morales, J.I. 2020, A new approach to measure reduction intensity on cores and tools on cobbles: the Volumetric Reconstruction Method. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, 12(222). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-020-01154-7

Lombao, D., Rabuñal, J., Cueva-Temprana, A. & Morales, J.I. 2023, Establishing a new workflow in the study of core reduction intensity and distribution. Journal of Lithic Studies, 10(2): 25 p. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2218/jls.7257

Macgregor, O. J. 2005, Abrupt terminations and stone artefact reduction potential. In: Lithics “Down Under”: Australian approaches to lithic reduction, use and classification (Clarkson, C. & Lamb, L., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1408. Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 57-65.

Maloney, T. R. 2020, Experimental and archaeological testing with 3D laser scanning reveals the limits of I/TMC as a reduction index for global scraper and point studies. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 29: 102068. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.102068

Maloney, T. R., O’Connor, S., & Balme, J. 2017, The effect of retouch intensity on mid to late Holocene unifacial and bifacial points from the Kimberley. Australian Archaeology, 83: 42-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2017.1350345

Marwick, B. 2008a, Beyond typologies: the reduction thesis and its implications for lithic assemblages in Southeast Asia. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association Bulletin, 28: 108-116. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7152/bippa.v28i0.12023

Marwick, B. 2008b, What attributes are important for the measurement of assemblage reduction intensity? Results from an experimental stone artefact assemblage with relevance to the Hoabinhian of mainland Southeast Asia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(5): 1189-1200. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2007.08.007

Marwick, B., Clarkson, C., O’Connor, S., & Collins, S. 2016, Early modern human lithic technology from Jerimalai, East Timor. Journal of Human Evolution, 101: 45-64. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004

McPherron, S. P. 1995, A re-examination of the British biface data. Lithics, 16: 47-63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004

Moore, M. W. 2000, Technology of Hunter Valley microlith assemblages, New South Wales. Australian Archaeology, 51: 28-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2000.11681678

Morales, J. I. 2016, Distribution patterns of stone-tool reduction: establishing frames of reference to approximate occupational features and formation processes in Paleolithic societies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 41: 231-245. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2016.01.004

Morrow, J. E. 1997, End scraper morphology and use-life: an approach for studying Paleoindian lithic technology and mobility. Lithic Technology, 22: 70-85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01977261.1997.11721069

Morrow, J. E., & Morrow, T. A. 2002, Exploring the Clovis Gainey-Folsom continuum: technological and morphological variation in Midwestern fluted points. Lithic Technology, 2: 141-157. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315428338-9

Muller, A., Clarkson, C., Baird, D., & Fairbairn, A. 2018, Reduction intensity of backed blades: blank consumption, regularity and efficiency at the Early Neolithic site of Boncuklu, Turkey. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 21: 721-732. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2018.08.042

Nguyen, D. T. & Clarkson, C. 2013, The organisation of drill production at a Neolithic lithic workshop site of Bai Ben, Cat Ba Island, Vietnam. Journal of Indo-Pacific Archaeology, 33: 24-39. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7152/bippa.v33i0.14508

Nguyen, D. T. & Clarkson, C. 2016, Typological transformation among Late Paleolithic flakes core tools in Vietnam: an examination of the Pa Muoi assemblage. Journal of Indo-Pacific Archaeology, 40: 32-41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.7152/jipa.v40i0.14963

Pollard, J. 1999, ‘These places have their moments’: thoughts on settlement practices in the British Neolithic. In: Making places in the prehistoric world: themes in settlement archaeology (Bruck, J. & Goodman, M., Eds.). University College Press, Dublin: p. 76-93.

Pollard, J. 2000, Neolithic occupation practices and social ecologies from Rinyo to Clacton. In: Neolithic Orkney in its European context (Ritchie, A., Ed.). McDonald Institute, Cambridge: p.363-369.

Riel-Salvatore, J., & Barton, C. M. 2004, Late Pleistocene technology, economic behaviour, and land-use dynamics in southern Italy. American Antiquity, 69(2): 257-274. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/4128419

Riel-Salvatore, J., Popescu, G., & Barton, C. M. 2008, Standing at the gates of Europe: human behavior and biogeography in the southern Carpathians during the Late Pleistocene. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 27: 399-417. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaa.2008.02.002

Rolland, N. 1977, New aspects of Middle Palaeolithic variability in Western Europe. Nature, 266: 251-252. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/266251a0

Rolland, N. 1981, The Interpretation of Middle Palaeolithic variability. Man, 16(1): 15-42. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2801973

Rolland, N., & Dibble, H. L. 1990, A new synthesis of Middle Paleolithic variability. American Antiquity, 55(3): 480-499. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2801973

Shott, M. J. 1995, How much is a scraper? Curation, use rates, and the formation of scraper assemblages. Lithic Technology, 20: 53-72. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01977261.1995.11720899

Shott, M. J. 1996, An exegesis of the curation concept. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 52: 259-280. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1086/jar.52.3.3630085

Shott, M. J. 2017, Stage and continuum approaches in prehistoric biface production: a North American perspective. PLoS ONE, 12(3): e0170947. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170947

Shott, M. J. 2024, Dibble’s reduction thesis: implications for global lithic analysis. Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, 7, 12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41982-024-00178-y

Shott, M. J., & Ballenger, J. A. M. 2007, Biface reduction and the measurement of Dalton curation: a southeastern United States case study. American Antiquity, 72: 153-175. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/40035302

Shott, M. J., & Seeman, M. F. 2015,. Curation and recycling: estimating Paleoindian endscraper curation rates at Nobles Pond, Ohio, USA. Quaternary International, 361: 319-331. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.023

Shott, M. J., & Weedman, K. J. 2007, Measuring reduction in stone tools: an ethnoarchaeological study of Gamo hidescrapers from Ethiopia. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 34(7): 1016-1035. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.09.009

Siegel, P. E. 1985, Edge angle as a functional indicator: a test. Lithic Technology, 14(2): 90- 94. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01977261.1985.11754508

Tabor, J., Billington, L., Healy, F., & Knight, M. 2016, Early Neolithic pits and artefact scatters at North Fen, Sutton Gault, Cambridgeshire. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 82: 161-191. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ppr.2016.2

Thomas, J. 1999, Understanding the Neolithic. Routledge, London, 266 p.

Wainwright, G. 1972, The excavation of a Neolithic settlement on Broome Heath, Ditchingham, Norfolk. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 38: 1-97. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0079497X00010925

White, P. J. 1967, Ethno-archaeology in New Guinea: two examples. Mankind, 6(9): 409-414. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-9310.1967.tb00357.x

Whittle, A. 1997, Moving on and moving around: Neolithic settlement mobility. In: Neolithic Landscapes (Topping, P., Ed.), Neolithic Studies Group Seminar Paper Vol. 2. Oxbow Books, Oxford: p. 15-22.

Whittle, A. 1999, The Neolithic period. In: The archaeology of Britain: an introduction from the Upper Palaeolithic to the Industrial Revolution (Hunter, J. & Ralston, I., Eds.). Routledge, London: p. 58-76.

Wilkinson, T. J., Murphy, P. L., Brown, N., & Heppell, E. M. (Eds.) 2012, The archaeology of the Essex Coast, volume II: excavations at the prehistoric site of the Stumble, East Anglian Archaeology Vol. 144. Essex County Council, Historic Environment, Chelmsford, 150 p.

Wilmsen, E. N. 1970, Lithic analysis and cultural inference: A Paleo-Indian case. Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona Vol. 16. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 87 p.

Descargas

Archivos adicionales

Publicado

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2025 Journal of Lithic Studies

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución 4.0.