Presenting LusoLit: A lithotheque of knappable raw materials from central and southern Portugal

1. ICArEHB - Interdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and

Evolution of Human Behavior, Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais,

Universidade do Algarve, Campus Gambelas 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. Email:

Pereira:

telmojrpereira@gmail.com; Paixão:

eduardo.paixao88@gmail.com

2. NAP - Núcleo dos Alunos de Arqueologia e Paleoecologia, Universidade do

Algarve, Campus Gambelas 8005-139 Faro, Portugal. Email: Farias:

annef.email@gmail.com

The knowledge of where past human populations collected their raw materials to produce stone-tools is crucial to understand subjects such as their territoriality, mobility, decision-making, range of acquisition, networks and, eventually, to infer their cognitive abilities and the adaptations to new environments, landscapes and territories. Therefore, the creation of lithic reference collections (lithotheque) is of utmost importance.

In geological terms, Portugal is a highly complex and diversified region, with a plethora of igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks dated from Proterozoic to present days. Such diversity might have influenced considerably the human decision-making on the choices of raw material and it might be one of the major reasons for the diversity seen throughout the diachrony of its archaeological record. Thus, sampling, cataloguing and mapping the raw material diversity in a territory with such variability allows to enrich the knowledge about it and, consequently to build stronger inferences about past human behaviour with more detail and less bias.

In order to help the archaeological and anthropological research to better understand such archaeological record and past human behaviour in this territory, we started a reference collection for this region host in the University of Algarve: the LusoLit. Though in its early stages, this collection has already several hundred chert samples from Central and Southern Portugal. In this early stage, the raw material that we start collecting was chert because it is the least ubiquitous through the landscape and, consequently, that can provide better information.

Keywords: LusoLit; lithotheque; knappable raw materials; abiotic resources; Portugal

The Western Europe empirical approach to explain nature, the world, the cosmos and the man has a history of centuries that can be tracked back at least to the Classic Greek Period. Despite that, the Aristotelic perspective was kept as main philosophic line of Nature’s explanation until the introduction of scientific novelties that gave a crucial thrust to the shift towards what is the modern science; many of those novelties were presented and compiled in the De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Copernicus 1543). One of the main - if not the major - reasons for this change is related to the increased power of the Ottoman Empire that seriously constrained the Western European commercial routes with the East, especially after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The change in the political, military and economic scenario demanded that Western European kingdoms sought alternative direct routes of trade with the East and that was only possible through inedited routes in the Atlantic.

Such overseas dynamics demanded a serious investment in scientific development but, more than that, it resulted in an overwhelming input of knowledge in geography, biology, geology and human populations. Rapidly it was understood that this rich, complex and interrelated information needed to be deeply explored, intensively collected, described in detail, congruently explained and exquisitely organized, if not because of more noble reasons, at least because they represented new resources. This enormous task is still ongoing, but was a phase of strong development between the second half of the 19th Century and the beginning of the I World War (Adams 1895; Cuvier 1817; Darwin 1859; 1871; Hume 1739; Hutton 1788; Lamarck 1809; Leclerc 1749; 1780; Linnaeus 1735; Lubbock 1870; 1872; Lyell 1830; 1863; Malthus 1798; Stenonis 1669; Wallace 1858). These empirical and systematic approaches to science quickly became fashionable across Europe, mostly due to the competition between researchers, institutions, regions and nations. Among other things, it resulted in the proliferation of state-of-the-art facilities such as new, large, modern and often beautiful infrastructures to host universities, museums, laboratories, societies and other institutions dedicated to culture and both the general and specific branches of science. Reference collections were started in many of them, including for geological specimens.

Such scenario towards empirical science was not strange in Portugal. Also in this country, there was a strong investment in science during the 19th Century and several rich and well organized reference collections were built, most of them in the major universities of Lisbon, Coimbra and Porto. In the case of geology, such reference collections - that included rocks, minerals and sediments - aimed towards knowledge and understanding of the Portuguese territory - both continental and overseas - and is deeply linked with the formation of the Comissão Geológica do Reino (Geological Commission of the Kingdom) in 1852, the Real Museu de História Natural (1768), the Natural History Museum of the Universities of Coimbra and Porto, the Sociedade Carlos Ribeiro (Carlos Ribeiro Society) in 1887 and the Escola Colonial (Colonial School) in 1906 (Poloni 2012).

In the case of the Comissão Geológica do Reino, the presence of researchers interested in the study of the origins and development of the World, nature and humanity such as Pereira da Costa (1809-1888), Carlos Ribeiro (1813-1882) and Nery Delgado (1835-1908) allowed a close relation between the investigation in Geology, Anthropology and Prehistory (Fabião 1999). This is clearly visible in the quality of the excavation, the detailed recording, the extensive description of Cova da Moura Cave (Delgado 1867), Furninha Cave (Delgado 1884), Cabeço da Arruda shellmidden (Costa 1865) and Cabeço da Amoreira shellmidden (Ribeiro, C. 1884), but also by the constant comparison with the evidence that was being found across Europe. The case of Nery Delgado is outstanding and an example of the high quality Palaeolithic research in Portugal at its beginning (Zilhão 1993). This commission - hereafter called Serviços Geológicos de Portugal (Portuguese Geological Services), Instituto Geológico e Mineiro (Geological and Mineralogical Institute) and now Laboratório Nacional de Energia e Geologia - (National Laboratory of Energy and Geology) - not only collected thousands of samples throughout the country, but also produced the 1:50000 scale geological maps and respective detailed Notícia Explicativa (Explanatory Note) that complete each one of these maps. This detailed cartography is still today the one used countrywide for a multiplicity of works, including the several approaches to archaeology and is now being improved at a scale of 1:25000 in both paper digital and shapefile formats.

From late 1980’s, especially with the arrival of Prof. Anthony Marks in 1987, there was an important shift in archaeological research not only with the beginning of well-funded interdisciplinary projects with a large number of students interested in develop their research (especially thesis and dissertations in the Portuguese Palaeolithic) but, probably most importantly, towards Processualist and Middle Range Theory. One of the tasks that was almost immediately started was the mapping, collection and description of chert sources. This information has been presented in academic theses and dissertations since the 1990s (Araújo 2012; Bicho 1992; Matias 2012; Pereira 2010; Santos 2005; Thacker 1996; Veríssimo 2004; 2005; Zilhão 1997) and also in journal articles and international meetings (Aubry & Igreja 2008; Aubry & Sampaio 1997; Aubry et al. 2001; 2004; 2012; 2014; Bicho 1994; 2002; Pereira et al., 2015a; 2015b; 2015c; Pereira & Carvalho 2015; Santos 2005; Shokler 2002; 2007; Thacker 2001; Veríssimo 2004; 2005) - some more specifically dedicated to raw materials than others, but all giving crucial information to answer questions related to sourcing, provisioning and mobility.

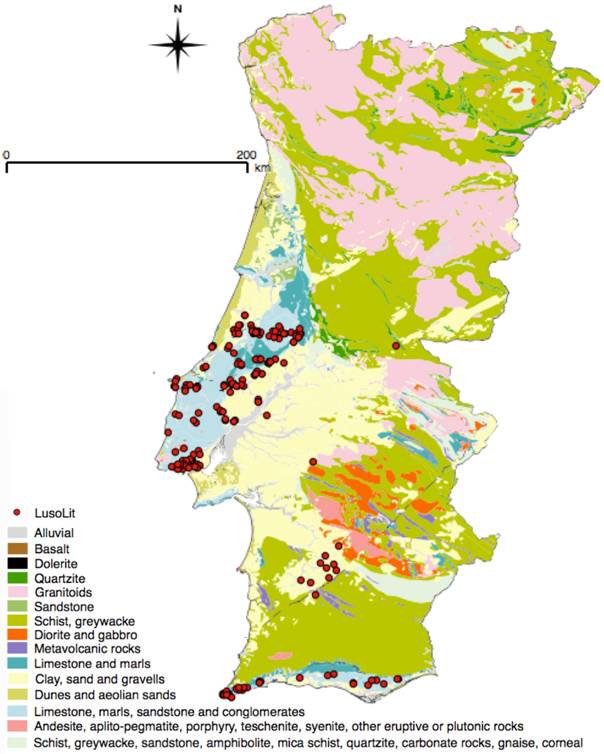

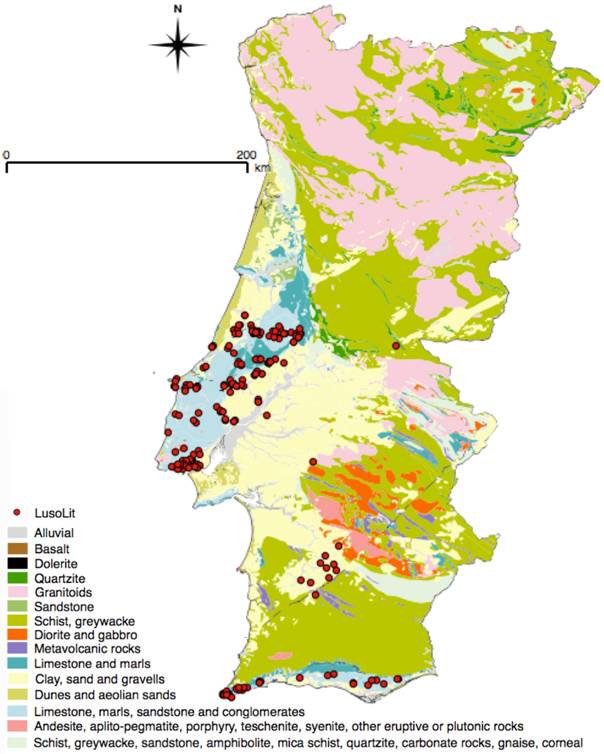

The Portuguese territory is mostly composed of sedimentary rocks such as Meso-Cenozoic limestone and Cenozoic sandstone along with meta-sedimentary rocks such as schist, greywacke and quartzite dated from the Precambrian and the Palaeozoic periods (Ribeiro, A. et al. 1979) (Figure 1). These last three make up around 70% of the territory, while limestone comprises around 12%. Over these bedrocks, there are abundant alluvial basins that, in the Tagus, Douro, Guadiana, Minho, Mondego and Lis rivers, can have thick and wide Pliocene-Pleistocene deposits (Ribeiro, A. et al. 1979; Almeida et al. 2000). Near the coast, there is also a significant (and almost continuous) strip of upraised Pliocene-Pleistocene marine deposits and Holocene dune fields that, in both cases, can extend to c.10 km inland. Finally, scatted through the landscape, there are some volcanic rocks (usually granite and basalt) of multiple ages.

In what concerns to the presence of the different raw materials used during Prehistory in each one of these geological backgrounds, it is often possible to find chert in both primary and secondary deposits throughout the landscape with limestone below. The former, in both the form of continuous lenses or as nodules within specific limestone layers and the last in relatively restricted patches sometimes of river or sea gravels (e.g., Andrade & Matias 2011; Aubry et al. 2012; 2014; Gaspar, 2009; Jordão, 2010; Matias 2012; Pereira, et al., in press; Ribeiro, C.A. 2005; Verissimo 2004). By contrast, the areas dominated by Precambrian and the Paleozoic rocks although not entirely dominated by quartzite have several outcrops of this rock, sometimes with monumental dimensions, a dense presence of quartz lenses often with decimetrical thickness, and also chert and jasper (Burke et al. 2011; Inverno et al. 2008; Matos & Sousa 2008).

One of our major concerns in the construction of this database is the comparison with the archaeological record. The sampling of the available primary and secondary sources of raw materials used somehow during Prehistoric times have been shown to be a fundamental tool to infer a multiplicity of features in hominine behaviour such as mobility (Crandell, et al. 2013; Eixea et al. 2014), acquisition areas (Aubry et al. 2004; Barberena et al. 2011; Crandell, et al. 2013; Dawson et al. 2012; Messineo & Barros 2015; Roldán et al. 2015;), territory and networks (Aubry et al. 2012; Djindjian et al. 2009 and references therein), resource management (Messineo & Barros 2015), lithic technology (Beck et al. 2002; Pereira & Benedetti 2013), adaptation (Brown 2011) and, possibly, cognition (Mcbrearty & Brooks 2000).

Figure 1. Simplified lithological map of the Portuguese territory with the chert sources present in the LusoLit database, build with the 1:1,000,000 shapefile of the lithological map produced by Instituto do Ambiente (Soares da Silva 1982). [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

Despite the effort made during the last three decades (Aubry, et al 2001; 2004; 2012; 2014; Bicho 1994; 2002; Aubry & Igreja 2008; Aubry & Sampaio 1997; Pereira et al. 2015a; 2015b; 2015c; Santos 2005; Shokler 2002; 2007; Thacker 2001; Veríssimo 2004; 2005), Portugal lacked the existence of an institutional infrastructure that hosted geological samples representable of the variety of raw materials existent in this territory and that could have been used in the past by human groups. This contrasted considerably with what happens in other countries where such reference collections exist in governmental research centres or universities for specific regions such as Catalonia (Mangado-Llach, et al. 2010; Sánchez et al. 2014; Terradas et al. 2012), Catalonia along with parts of Portugal and France (Mangado-Llach et al. 2010; Sánchez et al. 2014), Hungary in general (Biró 2008; Biro & Dobosi 1991a; 1991b), Mureş Valley (Crandell 2009), Languedoc-Roussillon (Grégoire et al. 2010), Charente Basin (Féblot-Augustins et al. 2010) among many others in Europe and across the world. In practical terms, what this situation meant was that, despite the considerable amount of geological sources of raw materials sampled to compare with the archaeological record, because there was no dedicated project integrating archaeologists, geologists and the national heritage institutions or a public place to make them available they were almost only for internal consumption (so to say) and, thus, unavailable in a comprehensible manner to the general academic community.

The LusoLit project aims to be a national reference collection (coped with a wide and comprehensible database for the available raw materials existent on the Portuguese territory.) of both primary and secondary sources that were or could have been used by human populations in the past. This infrastructure is being built in the facilities of the University of Algarve, without dedicated funding and as most as possible free of specific archaeological site project driven. It intends to have a proper and dedicated housing, physical conditions to grow, a comprehensive rich database associated, and to be available to all the scientific community.

Presently, the LusoLit database is under organization. It already has over 100 chert sources mapped (Figure 1), and is continuously increasing. Most of the sources have multiple specimens, which represent over 300 pure samples. Besides Portugal, there are also some samples of chert and silcrete from Spain, France, United States, South Africa and Germany. These samples have been offered by colleagues and have been kept in order to be used as control. In other words, if most analysis analyses - such as geochemical - are used to infer provenance, it is expected that these specimens will not cluster with those from the Portuguese territory.

In practical terms, the introduction of a new sample follows this sequence of passes: First, each source to be sampled is targeted based on information gathered from the bibliography, the geologic cartography, a fellow colleague with whom we are collaborating (e.g., archaeologist, geologist, geographer, anthropologist) or common person of the region being surveyed. Fortunately, the overall geological bibliography is very rich, although the information is not always easy to find because it is considerably dispersed in some cases in non-digital forms. In the case of the geological cartography, we have the fortune to have one that is often quite rich and detailed in what concerns the location of specific geological layers or locations where chert and other raw materials used in the past can be found.

Our fieldwork has been primarily focusing on chert because it embraces raw materials that are more localized in the landscape and, thus, are more useful for archaeologists and anthropologist to understand relevant features of human behaviour such as sourcing, territories, mobility and pathways. Nevertheless, other raw materials such as quartz, quartzite, jasper, lydite, greywacke and basalt have also been mapped and collected from primary and secondary sources, but in these cases in less quantity.

From each source (primary or secondary) we collect several entire nodules or chunks (these from outcrops) not only to cover the source variability, but also to have enough material to perform a multiplicity of analysis, including destructive. The reason behind the sampling of secondary sources is related with these being also potential areas of acquisition of lithic raw materials and, thus, cannot be neglected. Moreover, this will allow to understand better (1) through where the natural agents transported the debris eroded from the original outcrops and, thus, (2) which was the closest point to the archaeological sites where each type or sub-type of raw material could have been obtained. By doing that, we expect to have a clearer idea about the agent responsible for that transportation, i.e. natural, humans or a combination of both.

After being collected, the source is georeferenced as a point and, in the case of outcrops, their visible perimeter is marked as a polygon. In the beginning, this was done using a hand-held GPS but, more recently, we start using a tablet with an embedded GPS because the newer equipment is more accurate. Then, the source is photographed in different scales and angles, and the specimens are photographed, registered, collected, bagged and labelled. As a redundant procedure to avoid loss of information, each specimen is marked with a permanent pen with the coordinates while still in the field. This ensures that the information associated with the specimen and its relation with the source is not lost somewhere in the way between the field and the lab.

When the sample arrives to the laboratory, the information of each specimen is added to a database, after which it is exported to QGis and mounted in a multilayer file with the topography, geology, lithology, hydrology, bathymetry or other land features that may be considered relevant. Previously, this information was exported to GoogleEarth in order to get a more comprehensive framework of the relation between the sources and of the sites with the landscape but also between them. More recently, QGis offered the Openlayers plugin, where satellite photos and other features from OpenStreetMap, Google, Bing, MapQuest, OSM-Stamen and Apple are available, meaning that it is no longer necessary to leave QGis to have that visualization.

The diversity of analysis performed in each sample is wide considering both macro and microscopic features. For macroscopic analysis, the colours of each nodule are recorded using both the X-Rite Colortron available in the CIMA Laboratory of the University of Algarve and X-Rite Passport with calibrated studio lights. The first reads 1cm2 and, thus, provide us with a larger measurable color, while the second allows one to make the reading at the pixel level. Because these options are from the same company the values can be compared without calibration problems. This method is considerably more accurate than the Munsell Color Chart (Munsell Color 2009). Density is taken using a combination of digital scales - now being re-measured using a 0.01g scale - and graduate cylinders. Hardness and rebound values are recorded using a Schmidt Hammer - from the CIMA - Centre for Marine and Environmental Research of the University of Algarve - with the sample being held in an 18kg vice with 180 kg strength grip. Preliminary results of this investigation have already being presented elsewhere (Farias et al., 2015, 2016).

At the microscopic level, namely with regards to the chemical characterization and fabric, we give preference to non-destructive analysis that can retrieve measurable data. Because such analyses are quite expensive and we have been developing collaborative work with several institutions such as the Instituto Tecnológico e Nuclear, the Hercules Laboratory, and the University of South Florida. In the case of Instituto Tecnológico e Nuclear, T. Pereira received a research grant from Archaeological Institute of America (Portuguese Grant) to perform PIXE analysis on some chert samples from Central Portugal to be compared with stone tools made on cherts collected in Gruta Nova da Columbeira, Mira Nascente and Praia de Rei Cortiço (Pereira et al., 2015). In the case of Hercules Laboratory our collaboration resulted in a set of analysis (XRF, SEM-EDS and XRD) in geological samples and their comparison with chert tools from the Epipalaeolithic layer of Pena d’Água (Costa et al. 2015; Pereira et al. 2015), finally, our collaboration with Universityof South Florida is dedicated to the same type of analysis in the site of Vale Boi. Other collaborative projects are now ongoing.

In regards to the storage of the samples, the subdivision of larger nodules makes the individuals to fit into a maximum size of 7x8x5 cm that is the size of the slots in custom made poplar wood boxes (Figure 2). This subdivision creates samples for future analysis such as heat treatment and burning. The remaining volume is kept as reserve for future samplings such as thin sections. The poplar wood boxes are stored in steal shelves, while the larger blocks are stored in standard industrial plastic boxes. Each specimen has a specific slot in a specific wood box where a physical tag is added with part of the information related to the source. The specimen receives coordinates again in order to create redundancies and avoid mixing.

Figure 2. Custom-made poplar wood boxes with some of the hand geological samples from LusoLit.

The construction of LusoLit is a work-in-progress in an advance state of development. It has some hundred sources referenced in both the bibliography and cartography; several dozen of them already have multiple specimen samples large enough to describe with a relative security the internal variability of each source.

Until now it was used in preliminary and detailed investigations presented in three peer review papers, four posters and in international congresses. The first results were only based on the mapping of some regional sources and the comparison of the main visible macroscopic features with the cherts recovered from the Mesolithic site of Cabeço da Amoreira (Pereira et al., 2013; Pereira et al. 2015) and the Upper Palaeolithic site of Vale Boi (Pereira et al., in press). Then, within collaborative projects, we begin to approach the geochemical analysis of some chert sources from Estremadura and comparing them with archaeological cherts from the Mousterian sites of Gruta Nova da Columbeira, Mira Nascente and Praia de Rei Cortiço (Pereira et al., 2015). Then we tested other methods (XRF, SEM-EDS and XRD) comparing geological nodules with stone tools from the Epipalaeolithic site of Pena d´Água (Costa et al., 2015; Pereira et al. 2015). More recently, we have been approaching the physical characteristics of the geological sources comparing size, weight, density with hardness and rebound values (Farias et al., 2015, 2016). Together, these different approaches have been offering a wide range of perspectives on raw material characteristics, sourcing, hopping to shed light into past human behaviour.

Our future steps will be to continue sampling the primary and secondary sources, expand the analysis to all raw material collected and open this reference collection during 2017.

Presently, besides the organization of the data related with each one of the specimens, we are also creating the conditions to make the lithotheque a comfortable space available to external visitors. This includes a dedicated space in the University of Algarve, tables and chairs, a microscope, an informatics database - including with GIS data set- and a dedicated bibliographic and cartographic archive.

We would like to thank to Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portuguese Science Foundation) for the contract IF/01075/2013 to Pereira and the Associação dos Arqueólogos do Algarve (Archaeological Association of Algarve) for the grant to Farias to be present at the International Symposium on Knappable Materials (ISKM Barcelona 2015).

Adams, F. D. 1895, Hutton’s “Theory of the Earth.” Nature, 52(1354): 569-569. doi:10.1038/052569b0

Almeida, C., Mendonça, J. J. L., Jesus, M. R., & Gomes, A. J. 2000, Sistema Aquíferos de Portugal Continental, Centro de Geologia da Universidade de Lisboa & Instituto Nacional da Água, Lisbon, 661 p. (in Portuguese) (“Acquiferous Systems of Continental Portugal”)

Andrade, M.A. & Matias, H. 2011, Pedreira do Aires and Monte das Pedras: Two Neolithic Flint «Mines» In Lisbon Península. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of the UISPP. Commission on Flint Mining in Pre and Protohistoric Times: Flint Mining and Quarrying Techniques in Pre and Protohistoric Times (Capote, M., Consuerga, S., Diaz-Del-Rio, P. & Terradas, X., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 2260, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 149-156.

Araújo, A. C. 2012, Une Histoire des premières Communautés Mésolithiques au Portugal. Universite Paris I, Paris, 420 p. (in French) (“A History of the first Mesolithic Comunities of Portugal”)

Aubry, T., Chauvière, F.-X., Mangado Llach, X., & Sampaio, J. D. 2001, Constitution, territoires d’approvisionnement et fonction des sites du Paléolithique supérieur de la basse vallée du Côa (Portugal). In: Perceived Landscapes and Built Environments: The cultural geography of Late Paleolithic Eurasia. Archaeopress, Actes du XIVe. Colloque de la UISPP, Liége, 2-8 septembre 2001 (Vasil’ev, S.A., Soffer, O., Koslowski, J., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1122, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 83-92. (in French) (“Constitution, territories of procurement and function of the Upper Palaeolithic sites in the lower Côa valley (Portugal)”)

Aubry, T., & Igreja, M. 2008, Economy of lithic raw material during the Upper Palaeolithic of the Côa Valley and the Sicó Massif (Portugal): technological and functional perspectives. In: Proceedings of the workshop “Recent functional studies on non flint stone tools: methodological improvements and archaeological inferences” (Igreja, M., Clemente-Conte, I., Eds.), (CD-ROM), (ISBN 978-989-20-1803-4), Lisbon: p. 1-25.

Aubry, T., Luís, L., Mangado Llach, J., & Matias, H. 2012, We will be known by the tracks we leave behind: Exotic lithic raw materials, mobility and social networking among the Côa Valley foragers (Portugal). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 31(4): 528-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2012.05.003

Aubry, T., Mangado, J., & Matias, H. 2014, Matérias-primas das ferramentas em pedra lascada da Pré-história do Centro e Nordeste de Portugal. In: Proveniência de materiais geológicos: abordagens sobre o Quaternário de Portugal (Dinis, P., Gomes, A. & Monteiro-Rodrigues, S., Eds.), Associação Portuguesa para o Estudo do Quaternário (APEQ), Porto: p. 165-192. (in Portuguese) (“Raw materials of Prehistoric knapped stone tools from Central and Northeast Portugal”)

Aubry, T., Mangado Llach, J., Fullola, J. M., Rosell, L., & Sampaio, J. D. 2004, Raw Material Procurement in the Upper Paleolithic Settlements of the Côa Valley. (Portugal): New Data Concerning Modes of Resource Exploitation in Iberia. In: The Use of Living Space in Prehistory: Papers from a Session Held at the European Association of Archaeologist 6th Annual Meeting in Lisbon (Smyntyna, O. V., Ed.), BAR International Series Vol. 1224, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 37-50.

Aubry, T.; Sampaio, J. D. (1997). Exploração dos recursos em matérias primas líticas nas jazidas paleolíticas das bacias do Côa e da Ribeira de Aguiar. Poster presented at the Ias Jornadas do Quaternário de Portugal. Braga, Portugal. (in Portuguese) (“Exploitation of the resources in lithic raw materials of the Palaeolithic sites from Coa and Aguiar River Basins”)

Barberena, R., Hajduk, A., Gil, A. F., Neme, G. a., Durán, V., Glascock, M. D., Giesso, M., Borrazzo, K., de la Paz Pompei, M., Salgán, M.L., Cortegoso, V., Villarosa, G., Rughini, A.A. 2011, Obsidian in the south-central Andes: Geological, geochemical, and archaeological assessment of north Patagonian sources (Argentina). Quaternary International, 245(1): 25-36. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.09.013

Beck, C., Taylor, A. K., Jones, G. T., Fadem, C. M., Cook, C. R., & Millward, S. a. 2002, Rocks are heavy: transport costs and Paleoarchaic quarry behavior in the Great Basin. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 21(4): 481-507. doi:10.1016/S0278-4165(02)00007-7

Bicho, N. F. 1992, Technological change in the final Upper Paleolithic of Rio Maior, Portuguese Estremadura. PhD. Thesis. Southern Methodist University, Dallas, 454 p.

Bicho, N. F. 1994, The End of the Paleolithic and the Mesolithic in Portugal. Current Anthropology. 35(5): 664-674. doi:10.1086/204328

Bicho, N. F. 2002, Lithic Raw Material Economy and Hunter-Gatherer Mobility in the Late Glacial and Early Postglacial in Portuguese Prehistory. In: Lithic Raw Material Economies in Late Glacial and Early Postglacial Europe (Fisher, L. E. & Eriksen, B. V. Eds.), Bar International Series Vol. 1093, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 161-179.

Biró, K. T. 2008, Comparative Raw Material Collections in Support of Petroarchaeological Studies: An Overview. In: Papers in honour of Viola T. Dobosi (Biró, K. T. & Markó, A. Eds.), Hungarian National Museum, Budapest: p. 225-244.

Biro, K. T., & Dobosi, V. T. 1991, LITOTHECA - Lithotheca Comparativ e Raw Materíal Collection of the Hungarían National Museum. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, 275 p.

Biró, K. T., & Dobosi, V. T. 1991, LITHOTHECA II: comparative raw material collection of the Hungarian National Museum. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest, 338 p.

Brown, K. S. 2011, The Sword in the Stone: Lithic Raw Material Exploitation in the Middle Stone Age at Pinnacle Point Site 5-6, Southern Cape, South Africa. University of Cape Town, South Africa, 396 p.

Burke, A., Meignen, L., Bisson, M., Pimentel, N., Henriques, V., Andrade, C., da Conceição Freitas, M., Kageyama, M., Fletcher, W., Parslow, C., Guiducci, D. 2011, The Palaeolithic occupation of southern Alentejo: The Sado River Drainage Survey. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 68(1): 25-49. doi:10.3989/tp.2011.11057

Copernicus, N. 1543, De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium. libri 6, apud Ioh. Petreium, Nuremberg, 196 p. (in Latin) (“On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres”)

da Costa, F. A. P. 1865, Da existência do homem em epochas remotas no valle do Tejo. Noticia sobre os esqueletos humanos descobertos no Cabeço da Arruda. Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 58 p. (in Portuguese) (“Of the existence of Man in remote epochs in the Tagus Valley. Notice on the human skeletons found in Cabeço da Arruda”)

Costa, M., Pereira, T., Andrade, C., Farias, A., Mirão, J. & Carvalho, A. (2015). Lithic economy and territory of Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers in the Middle Tagus: The case of Pena d'Água (Portugal). Poster presented at the XI Congresso Ibérico De Arqueometria, Évora, Portugal.

Crandell, O. 2009, Romanian Lithotheque Project: Knappable stone resources in the Mureş Valley, Romania. Studia Universitatis Babeş-Bolyai, Geologia, Special Issue, MAEGS-16: 79-80.

Crandell, O., Nita, L., & Anghelinu, M. 2013, Long-distance imported lithic raw materials at the Upper Palaeolithic sites of the Bistrița Valley (Carpathian mts.), Eastern Romania. Lithics, 34(1): 30-42.

Cuvier, G. 1817, Le Règne Animal Distribué D’après Son Organisation Pour Servir De Base À L'histoire Naturelle des Animaux, Et D'introduction À L'anatomie Comparée. Vol. 5. Chez Déterville, Paris, 556 p. (in French) (“The animal kingdom arranged according to its organization as a basis in natural history of animals, and an introduction to comparative anatomy”)

Darwin, C. 1859, On the Origin of Species. John Murray, London, 502 p.

Darwin, C. 1871, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Vol. 2. John Murray, London, 475 p.

Dawson, M.-C., Bernard-Guelle, S., Rué, M., & Fernandes, P. 2012, New data on the exploitation of flint outcrops during the Middle Palaeolithic: the Mousterian workshop of Chêne Vert at Dirac (Charente, France). Paleo, 23: 55-84. URL: https://paleo.revues.org/2464

Delgado, J. F. N. 1884, La Grotte de Furninha a Peniche. In: Congrès International d’Anthropologie et d’Archéologie préhistoriques. Compte rendu de la neuvième session à Lisbonne (1880). Académie Royale des Sciences, Lisbon: p. 207-279. (in French) (“The Furinha Cave at Peniche”)

DGMSG, Direcção Geral de Minas e Serviços Geológicos. 1968, Carta Geológica de Portugal, na escala de 1:1 000 000. Direcção Geral de Minas e Serviços Geológicos, Lisbon. (in Portuguese) (“Geological Map of Portugal at the scale of 1:1 000 000”)

Djindjian, F., Kozlowski, J. K., & Bicho, N. F. 2009, Le concept de territoires dans le Paléolithique supérieur européen, BAR Vol. 1938. British Archaeological Reports, Oxford, 262 p. (in French) (“The concept of territories in the European Upper Palaeolithic”)

Eixea, A., Roldán, C., Villaverde, V., & Zilhão, J. 2014, Middle Palaeolithic flint procurement in Central Mediterranean Iberia: Implications for human mobility. Journal of Lithic Studies, 1(1): 1-13. doi:10.2218/jls.v1i1.783

Fabião, C. 1999, Um Século de Arqueologia em Portugal I. Al-Madan, 8(2): 104-126. (in Portuguese) (“One Century of Archaeology in Portugal”)

Farias, A., Andrade, C., Pereira, T. (2015). The role of quality in raw material choice: Chert of Central (Estremadura) and Southern (Algarve) Portugal. Poster presented at the International Symposium on Knappable Materials, Barcelona, Spain.

Farias, A., Andrade, C., Pereira, T. (2016). How the rebound value is quality factor of the chert? Poster presented at the Raw materials exploitation in prehistory: Sourcing, processing and distribution, Faro, Portugal.

Féblot-Augustins, J., Park, S.-J., & Delagnes, A. (2010), État des lieux de la lithothèque du bassin de la Charente, Unpublished manuscript,72 p. (in French) (“Inventory of the lithotheque of the Charente basin”) URL: http://www.alienor.org/publications/bibliotheque-lithotheque/lithotheque-charente_2010.pdf

Gaspar, R. 2009, Estudo petroarqueológico da utensilagem lítica do sítio arqueológico Lajinha 8 (Évora, Portugal). Análise de proveniências. Master thesis. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, 52 p. (in Portuguese) (“Petroarchaeological Study of the Lithic Assemblage of the Archaeological Site Lajinha 8 (Évora, Portugal). Provenance analysis”)

Grégoire, S., Bazile, F., Boccaccio, G., Menras, C., Pois, V., & Saos, T. 2010, Les Ressources Siliceuses En Languedoc-Roussillon. Bilan Des Données Acquises. In: Silex et territoire préhistoriques. Avancées des recherches dans le Midi de la France. Les cahiers de Géopré, Centre Européen de Recherches Préhistoriques, Tautavel: p. 12-18. (in French) (“Siliceous Resources in Languedoc-Roussillon. Summary of the data acquired”)

Hume, D. 1739. A Treatise of Human Nature. (Selby-Bigge, L. A. Ed.), Liberty Fund Inc., Clarendon, Oxford, 368 p.

Hutton, J. (1788). Theory of the Earth; or An investigation of the laws observable in the composition, dissolution, and restoration of land upon the globe. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, 1(02): 209-304. doi:10.1017/S0080456800029227

Inverno, C. M. C., Solomon, M., Barton, M. D., & Foden, J. 2008, The Cu stockwork and massive sulfide ore of the Feitais volcanic-hosted massive sulfide deposit, Aljustrel, Iberian Pyrite Belt, Portugal: A mineralogical, fluid inclusion, and isotopic investigation. Economic Geology, 103(1): 241-267. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.103.1.241

Jordão, P. 2010, Análise de proveniências de matérias-primas líticas da indústria de pedra lascada do povoado calcolítico de São Mamede (Bombarral). Master thesis. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, 119 p. (in Portuguese) [“Provenance analysis of lithic raw materials of the lithic assemblage from the Chalcolithic settlement of São Mamede (Bombarral) “].

Lamarck, J. B. 1809, Philosophie Zoologique, Museum d'Histoire Naturelle, 2 volumes. Dentu, Paris, 429p. 475 p. (in Latin) (“Zoological Philosophy”)

Leclerc, G.-L. 1749, Histoire Naturelle, Générale Et Particulière, Avec La Description Du Cabinet Du Roi. Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 36 volumes. (in French) (“Natural history, general and particular, with the description of the Kings office”)

Leclerc, G.-L. 1780, Les Époques De La Nature. De l’Imprimerie Royale, Paris, 546 p. (in French) (“The epochs of the nature”)

Linnaeus, C. 1735, Systema Naturae Per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, Cum Characteribus Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. L. Salvius, Stockholm, 10 p. (in Latin) (“System of nature through the three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characters, differences, synonyms, places”)

Lubbock, J. 1870, On the Origin of Civilisation and the Primitive Condition of Man. Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London, 6: 328-341. doi:10.2307/3014269

Lubbock, J. 1872, Prehistoric times, as illustrated by ancient remains, and the manners and customs of modern savages. Williams and Norgate, London, 640 p.

Lyell, S. C. 1830, Principles of geology; Being an attempt to explain the former changes of the Earth’s surface, by reference to causes now in operation. 3 volumes. John Murray. London, 64 p., 364 p., 566 p.

Lyell, S. C. 1863, The Antiquity of Man, With Remarks on Theories of the Origin of Species by Variation. G. W. Childs, Philadelphia, 544 p.

Malthus, T. 1798, An essay on the principle of population as it affects the future improvement of society with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other writers. Printed for J. Johnson, in St. Paul’s church-yard, London, 430 p.

Mangado-Llach, X., Medina, B. M., & Casado, A. 2010, Lithic_UB: Un projet de lithothèque a l’Université de Barcelone. Les Cahiers de Géopré, (Silex et territoire préhistoriques. Avancées des recherches dans le Midi de la France) 1: Electronic publication. p. 51-54. (in French) (“Lithic_UB: A lithotheque project at the University of Barcelona”)

Matias, H. 2012, O Aprovisionamento de Matérias-primas Líticas na Gruta da Oliveira (Torres Novas). Master thesis. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, 135 p. (in Portuguese) (“The acquisition of lithic raw materials in Oliveira Cave”)

Matos, J. X., & Sousa, P. 2008, Prospecção de sulfuretos maciços no sector português da Faixa Piritosa Ibérica. In: 5º Congresso Luso-Moçambicano de Engenharia; 2º Congresso de Engenharia de Moçambique (Maputo, Moçambique, 2 a 4 de Setembro de 2008). Edições INEGI, Porto, Maputo: p. 1-2 (in Portuguese) (“Survey of massive sulphides in the Portuguese sector of the Iberian Pyrite Belt”) URL: http://www.lneg.pt/download/3815/12R015.pdf

Mcbrearty, S., & Brooks, A. S. 2000, The revolution that wasn’t: a new interpretation of the origin of modern human behavior. Journal of Human Evolution, 39(5): 453-563. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0435

Messineo, P. G., & Barros, M. P. 2015, Lithic Raw Materials and Modes of Exploitation in Quarries and Workshops from the Center of the Pampa Grasslands of Argentina. Lithic Technology, 40(1): 3-20. doi:10:1179/2051618514Y.0000000007

Munsell Color 2009, Munsell geological rock-color charts. Munsell Color, X-Rite, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 12 p

Pereira, T. 2010, A Exploração do Quartzito na Faixa Atlântica Peninsular no Final do Plistocénico. Doctoral Thesis, University of Algarve, Algarve, 435 p. (in Portuguese) (“The quartzite exploitation in the Atlantic strip of the [Iberian] Peninsula at the end of the Pleistocene”)

Pereira, T., Andrade, C., Costa, M., Farias, A., Mirão, J., & Carvalho, A. F. 2015, Lithic economy and territory of Epipaleolithic hunter-gatherers in the Middle Tagus: The case of Pena d’Água (Portugal). Quaternary International. 412: 135-144. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.081

Pereira, T., & Benedetti, M. M. 2013, A model for raw material management as a response to local and global environmental constraints. Quaternary International, 318: 19-32. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.04.011

Pereira, T., Bicho, N. F., Cascalheira, J., Gonçalves, C., Marreiros, J., & Paixão, E. 2015, Raw Material Procurement in Cabeço da Amoreira, Muge, Portugal. In: Proceedings of The Muge 150th Anniversary (Bicho, N. F. & Detry, C. Eds.), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Cambridge: p. 147-160.

Pereira, T., Bicho, N. F., Cascalheira, J., Gonçalves, C., Marreiros, J., & Paixão, E.( 2015). Raw Material Procurement in Cabeço da Amoreira, Muge, Portugal. Poster presented at Muge 150th anniversary, Muge, Portugal.

Pereira, T., Bicho, N. F., Cascalheira, J., Infantini, L., Marreiros, J., Paixão, E., & Terradas, X. in press. Territory and abiotic resources between 33 and 15.6 ka at Vale Boi (SW Portugal). Quaternary International, 412(A): 124-134. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.071

Pereira, T., & Carvalho, A. F. 2015, Abrupt technological change at the 8.2 ky cal BP climatic event in Central Portugal. The Epipalaeolithic of Pena d’Água Rock-shelter. Comptes Rendus - Palevol, 14(5): 423-435. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2015.04.003

Pereira, T., Manso, C., Alves, E., Alves, L., Benedetti, M., & Bicho, N. (2015). The Neanderthal Cognition: Chert Procurement in SW Iberia using PIXE Analysis. Poster presented at the Archaeological Institute of America meeting. New Orleans, USA.

Poloni, R. J. S. 2012, Expedições arqueológicas nos territórios de Ultramar: uma visão da ciência e da sociedade portuguesa do período colonial. Doctoral Thesis, University of Algarve, Algarve, 487 p. (in Portuguese) (“Archaeological expeditions in overseas territories: a vision of science and Portuguese society of the colonial period”)

Ribeiro, A., Antunes, M., Ferreira, M., Rocha, R., Soares, A., Zbyszewski, G., Almeida, F. M. & Monteiro, J. H. 1979, Introduction à la géologie générale du Portugal. Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisbon, 114 p. (in French) (“Introduction to the general geology of Portugal”)

Ribeiro, C. 1884, Les Kioekkenmoeddings de la vallée du Tage. In: Congrès International d'Anthropologie et d'Archeologie Prehistoriques, 9ª, Lisboa, 1880. Compte Rendue. Academia Real das Ciências de Lisboa, Lisbon: p. 279-292. (in French) (“The shellmiddens of the Tagus valley”)

Ribeiro, C. A. 2005, Evolução Diagenética e Tectono-Sedimentar do Carixiano da Região de Sagres, Bacia Algarvia. Doctoral Thesis, University of Évora, Évora, 333 p. (in Portuguese) (“Diagenetic and Tectonic-Sedimentary evolution of the Carixiano of Sagres Region Algarve Basin”)

Roldán, C., Carballo, J., Murcia, S., Eixea, A., Villaverde, V., & Zilhão, J., 2015, Identification of local and allochthonous flint artefacts from the Middle Palaeolithical site “Abrigo de la Quebrada” (Chelva, Valencia, Spain) by macroscopic and physicochemical methods. X-Ray Spectrometry, 44(4): 209-216. doi:10.1002/xrs.2602

Sánchez, M., Rey, M., Rodríguez, N., Casado, A., Medina, B., & Mangado, X., 2014, The LithicUB project: A virtual lithotheque of siliceous rocks at the University of Barcelona. Journal of Lithic Studies, 1(1): 281-292. doi:10.2218/jls.v1i1.756

Santos, E. 2005, Estudo preliminar das matérias-primas líticas de Vale Boi (Vila do Bispo, Algarve). In: O Paleolítico: Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular (Faro, 14 a 19 de Setembro de 2004), Centro de Estudos de Património, Faro: p. 447-456. (in Portuguese) (“Preliminary study of lithic raw materials Boi Valley (Vila do Bispo, Algarve)”)

Shokler, J. E., 2002, Approaches to the Sourcing of Flint in Archaeological Contexts: Results of Research from Portuguese Estremadura, In: Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone (Asmosia 5) (Herrmann, J. Jr., Herz, N., & Newman, R. Eds), Archetype Publications, London: p. 176-187.

Shokler, J. E. 2007, Hunter-Gatherer Movement in the Portuguese Upper Paleolithic: Archaeological Results of a Regional Lithic Sourcing Project. In: From the Mediterranean basin to the Portuguese Atlantic shore: Papers in Honor of Anthony Marks - Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular (Ferreira Bicho, N. (Ed.), Universidade do Algarve, Faro: p. 141-161. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Soares da Silva, A.M. 1982, Carta I.13 - Carta Litológica de Portugal Continental 1:1.000.000. Comissão Nacional do Ambiente, Lisbon. (in Portuguese) ("Map I.13 - Lithological Map of the Continental Portugal 1:1.000.000")

Stenonis, N. 1669, Nicolai Stenonis. De Solido Intra Solidum Naturaliter Contento. Dissertationis Prodromus. Ex Typographia Sub Signo Stellae, Florence, 78 p. (in Latin) (“Nicolai Stenonis. Dissertation on a solid naturally contained within a solid”)

Terradas, X., Ortega, D., & Boix, J. 2012, El projecte LitoCAT. Creació d’una litoteca de referència de roques silícies de Catalunya. Tribuna d’Arqueologia, 2010-2011: 131-150. (in Catalan) (“The project LitoCAT. Creating a reference lithotheque for the siliceous rocks of Catalonia”)

Thacker, P. T. 1996, A Landscape Perspective on Upper Paleolithic Settlement in Portuguese Estremadura. Perspective. Doctoral thesis. Southern Methodist University, Dallas, 360 p.

Thacker, P. T. 2001, The Aurignacian campsite at Chainça, and its relevance for the earliest Upper Palaeolithic settlement of the Rio Maior vicinity. Revista Portuguesa De Arqueologia, 4(1): 5-15.

Veríssimo, H. 2004, Jazidas siliciosas da região de Vila do Bispo (Algarve). Promontoria, 2: 35-47. (in Portuguese) (“Siliceous deposits of Vila do Bispo region (Algarve)”)

Veríssimo, H. 2005, Aprovisionamento de matérias-primas líticas na Pré-História do concelho de Vila do Bispo (Algarve). In: O Paleolítico: Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular (Faro, 14 a 19 de Setembro de 2004), Centro de Estudos de Património, Faro: p. 509-523. (in Portuguese) (“Acquisition of lithic raw materials in the Prehistory of Vila do Bispo municipality (Algarve)”)

Wallace, A. R. 1858, On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely from Original Type. John Van Voorst, London, 9 p.

Zilhão, J. 1993, As origens da Arqueologia paleolítica em Portugal e a obra metodologicamente percursora de J. F. Nery Delgado. Arqueologia & História, 10(3): 3-17. (in Portuguese) (“The origins of Palaeolithic Archaeology in Portugal and the methodologically pioneer work of J. F. Delgado”)

Zilhão, J. 1997, O Paleolítico Superior da Estremadura portuguesa, Vol. 2. Colibri, Lisbon, 1160 p. (in Portuguese) (“The Upper Palaeolithic of the Portuguese Estremadura”)