Conventions in fresh water fishing in the prehistoric southern Levant: The evidence from the study of Neolithic Beisamoun notched pebbles

1. Laboratory for Ground Stone Tools Research, Zinman

Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel.

Email: Rosenberg: drosenberg@research.haifa.ac.il;

Agnon: murf.agnon@gmail.com

2. Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel.

Email: dkaufman@research.haifa.ac.il

Fishing gear is not frequently found in archaeological sites in the southern Levant. Bone hooks were found as early as the later Epipalaeolithic period (mainly in Natufian culture sites) and continue to appear in small numbers until the Chalcolithic period, when the first copper hooks are found. But for most sites, we have scant information about fishing gear or techniques. The paucity of fishing gear in archaeological assemblages is notable and holds true for sites near the former Mediterranean Sea shore and for inland sites situated near fresh water sources. This may be attributed to preservation issues, in part, but also seems to reflect preferences in the selection of raw material for making various fishing implements. The present paper discusses a specific type of fishing gear, the notched pebbles. These implements are small pebbles with various degrees of modification - sometime including notable modification of the original pebble by flaking and sometimes only slightly modifying it by creating the two opposed notches. We will use the assemblage found at the Neolithic site of Beisamoun, in the Hula Valley, northern Israel as a test-case for discussing raw material and other preferences and long-term aspects of conventions in fresh water fishing gear.

Keywords: notched stone weights; fishing; southern Levant; Hula Valley; Neolithic period; ground stone tools

The use of fish as an important source of food should probably be attributed to the Lower Palaeolithic (Zohar et al. 2014). Unambiguous fishing gear however, seems to appear for the first time during the later parts of the Epipalaeolithic period in the context of the Natufian culture (e.g., Bar-Yosef & Belfer-Cohen 1989: 470; Bar-Yosef 1998: 165). Although fishing was discussed in the past in relation to seashore sites, specifically concerning the exploitation of marine resources (e.g., Galili et al. 2003; Galili et al. 2004), clear, direct evidence for fishing gear is relatively scarce, although a few stone weights may have been used as net sinkers, and a bone hook was discovered at Atlit Yam (Galili et al. 2004: figs. 6, 12a).

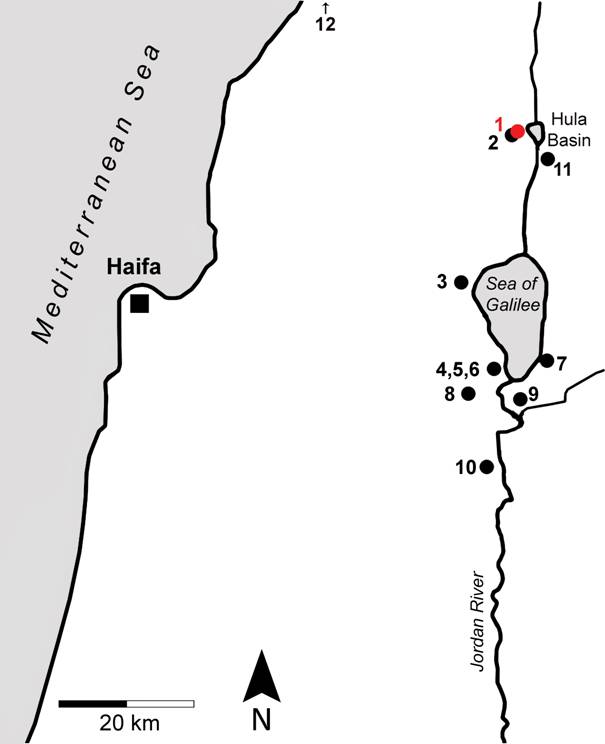

In recent years, however, a specific type of stone artefact has been commonly referred to as fishing gear. These items, small pebbles bearing two opposed notches, often termed “notched pebbles”, “fishing weights” or “notched weights” (see Rosenberg 2011, Type J1), were found in sites dated to different periods, all located near permanent water sources (Figure 1). These include sites such as Late Upper Palaeolithic Ohalo II at the Sea of Galilee (Nadel & Zaidner 2002; Zaidner 2002), the Epipalaeolithic site of Jordan River Dureijat (Marder et al. 2015: 13), the Late Epipalaeolithic, Natufian site of Eynan in the Hula Valley (Perrot 1966; Valla et al. 1998), as well as undated surface finds at Ha'aon Beach and Ohalo I, Sea of Galilee (Nadel & Zaidner 2002: 50). The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A is represented by the site of ‘Ein Dishna west of the Sea of Galilee (Vered & Birkenfeld 2015).

Figure 1. South Levantine sites in which notched pebbles were found: 1. Beisamoun, 2. Eynan, 3. ‘Ein Dishna, 4. Ohalo I, 5. Ohalo II, 6. Beit Yerach, 7. Ha’aon Beach, 8. Tel Ali, 9. Sha’ar Ha’golan, 10. Munhata; 11. Jordan River Dureijat; 12. Ras Shamra.

Pottery Neolithic sites in the Jordan Valley include Sha'ar Ha'golan (Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014), Neolithic Tel ‘Ali (Prausnitz 1970: 91, fig. 32: 4-5), Munhata (Gopher & Orrelle 1995a: fig. 46: 16-17); the Early Bronze Age site of Beit Yerach (Rosenberg & Greenberg 2014) is also located in this region. Similar items were noted at other sites in the Levant such as Abu Hureyra where at least some notched pebbles were found in clusters (Moore 2000: 174-176) and Ras Shamra, where dozens of such items made of limestone and sandstone were noted in Phases VA1-4, VB and VIC4 (de Contenson 1992: 98, figs. 128: 11-15, 131: 1-7, 132: 9).

The ethnographic record also adds evidence for the use of notched pebbles. For instance, the Eastern Cherokee used similar items in the pre- and post-contact periods (Altman & Ebrary 2006: 38-39). Other examples are known from the northwest coast of America where they were used as sinkers for fishing lines and nets (Rau 1884: 156). On the banks of the Colombia River, some notched sinkers were found on the surface (Smith 1910: 30-31). Similar items were also reported from Africa (Sandelowski 1970), and in sites in the Near East, Arabia, and around the Black Sea (Potts 2012: 226-227).

The largest assemblage of notched pebbles currently known was found at the Neolithic site of Beisamoun in the Hula Valley, Israel. The current paper describes this unique assemblage and compares its attributes to other published assemblages in order to discuss long-term preferences and conventions (morphological, technological and metrical) in fresh water fishing gear in the southern Levant.

The site of Beisamoun lies at the feet of the Naphtali Mountains in the Hula Valley, northern Israel, situated approximately 12 km south of the city of Qiryat Shemona (Figure 1). The greater prehistoric site of Beisamoun stretches from the Naphtali Mountains eastward to the Golan Heights and covers an area of ca. 400 dunams. It is, in fact, a cluster of smaller, independent occupations.

In the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s the site was thoroughly surveyed and probed by a French delegation (Lechevallier 1978). The excavations revealed an abundance of finds that dated the northern parts of the site mainly to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and to the Wadi Rabah culture (Perrot 1975; Lechevallier 1978: 127). Two additional series of trenches were dug to the southwest of the previously tested area (Lechevallier 1978: 127) revealing mainly Wadi Rabah material. Surface material collected from this part of the site also suggested a substantial presence for the Wadi Rabah culture in this area of Beisamoun (Rosenberg et al. 2006).

Excavations resumed in 2007 in the area adjacent to the western margins of the previous excavations, revealing Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, Pottery Neolithic and Early Bronze Age materials (Bocquentin et al. 2007; Bocquentin et al. 2014). During 2007, the Israel Antiquities Authority dug several trenches with a backhoe, followed by a test excavation, on the southwestern edge of the site. These excavations revealed Pottery Neolithic material attributed to the Yarmukian culture (Khalaily et al. 2009, Yegorov 2011; Khalaily et al. 2015). An extensive salvage excavation was conducted during the autumn of 2007 in an area adjacent to the Israel Antiquities Authority test excavation (Rosenberg 2010), focusing on the margins of the Pottery Neolithic hamlet.

Most of the finds from this site were retrieved during intensive surface collections since the early 1960s (A. Assaf pers. com.). These collections include thousands of artefacts that should be dated to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, Pottery Neolithic and Wadi Rabah cultures, as well as to the Early Bronze Age. One of the notable collections from these surveys includes hundreds of ground stone implements mostly made of basalt and limestone. Within the ground stone assemblage an important group of nearly a hundred notched pebbles were noted and studied (a few other notched pebbles were on display or otherwise not available for research).

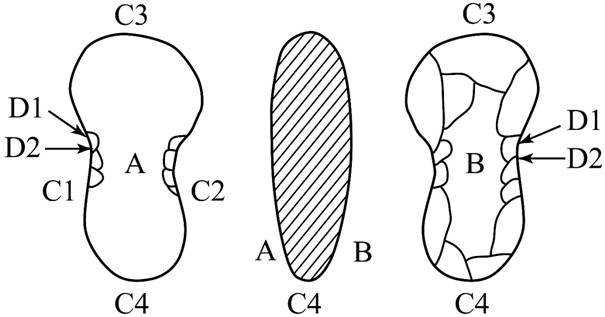

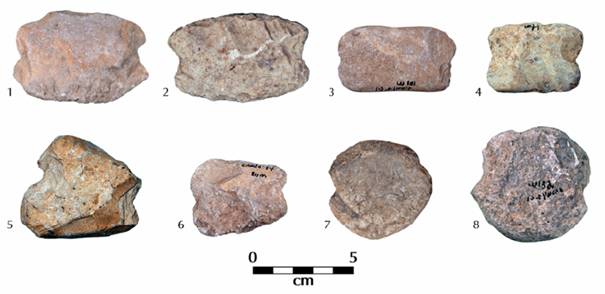

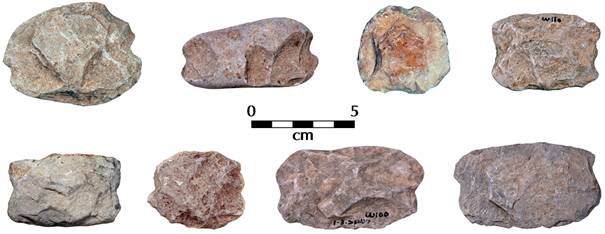

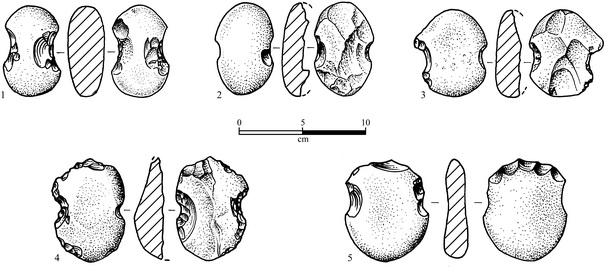

The assemblage studied here includes most of the notched pebbles from Beisamoun (n=96), notably the largest assemblage of notched pebbles in the southern Levant (Figure 2).

Although these are rather 'simple' items in terms of morphology and, usually, in terms of blank modification as well, the way they were utilized is more complex. These were probably used as weights of some kind, and no use-wear evidence for other uses of the pebbles or the notches (e.g., for sharpening, smoothing etc.) have been observed. Previous studies suggested their use as net sinkers or weights for underwater traps (Nadel & Zaidner 2002). If indeed these were used as net sinkers, it seems more likely that they were used as sinkers for throwing nets like the Mediterranean shabake rather than for fixed nets or traps due to their light weight (Rosenberg 2011; Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014). However, we think that these may have been used primarily as weights for fishing rods or fishing lines (see also Moore 2000: 174-176, fig. 7.15; Pajdla 2014: 24).

Figure 2. A selection of notched pebbles from Beisamoun.

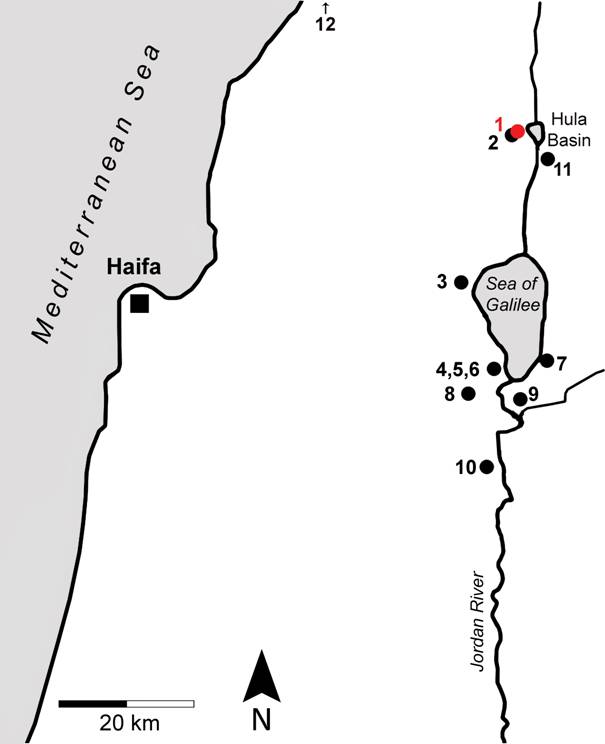

The definition of notched pebbles is rather straightforward. Most are flat, oval or sub-rectangular limestone pebbles on which two opposed notches were produced by flaking (Rosenberg 2011). A notched pebble (Figure 3) has two faces (A and B) and circumference (C). Each notch has an ‘edge’ or shoulder (D1), which is the elevated area at the face of the pebble, and a ‘base’ formed by the deeper area of the notch, which cuts down towards the middle of the pebble (D2). An entire face (A or B) of the notched pebble, or only part of one or both faces, may show scars resulting from flakes removed from the pebble’s margins which were used as striking platforms.

Our methodology follows Rosenberg (2011). In order to test the presence of conventions, it includes studying attributes such as raw material selection, preservation, blank characteristics, modification (e.g., presence of a totally flaked face), and metrics. Each weight was weighed and measured. Length and width was measured in three places (measured near the edges and in the middle of the pebble) while thickness was measured in two places (maximum and minimum). Specific attention was given to the notches' characteristics such as location (on the long or short sides of the pebble), metrics, and technology of production in order to better understand the characteristics of the string that tied these and held them in place. Measurements include notch width, depth and the relative width of the notch compared to the 'shoulders' width and to the opposed notch. Some notched pebbles are broken and incomplete and this is reflected in the different number of measured items for each attribute measurement.

Figure 3. Notched pebbles: A schematic depiction of main features (after Rosenberg and Garfinkel 2014: fig. 11.3). A and B are the two faces of the pebble, C defines the circumference (the longer sides are denoted C1 and C2, while the shorter ones are termed C3 and C4). D1 defines the notches' edges while D2 marks the ‘base’ of each notch.

In terms of raw material selection, there is a clear preference for limestone or dolomite pebbles (over 95% of the assemblage). These most likely originated from the nearby Naphtali Mountains, just west of the site. Basalt that can also be obtained at a short distance (only 2-3 kilometres) from the site was not selected. The remaining items were not identified.

The blanks selected for producing notched pebbles at Beisamoun are usually small, flat white to gray pebbles with lenticular or irregular cross-sections (Table 1). Most of these are oval (Figure 4: 1-2; 42.5%) and seem to follow the common natural outline of the pebbles that can be found near the site. The rest are rectangular (Figure 4: 3-4; 8.5%), trapezoidal (Figure 4: 5-6; 16%), rounded (Figure 4: 7-8; 5.3%) or irregular (27.6%).

Table 1. Summary of blank attributes. Stdev=Standard deviation

|

Attribute |

Measured items |

Range |

Average |

Stdev. |

|

Length I (mm) |

88 |

37-100 |

60.2 |

12.2 |

|

Length II (mm) |

92 |

42-97 |

60.3 |

11.2 |

|

Length between notches (mm) |

90 |

35-91 |

32.2 |

14.5 |

|

Width I (mm) |

95 |

20-75 |

36.4 |

10.4 |

|

Width II (Middle) (mm) |

96 |

31-90 |

47.1 |

11.8 |

|

Width III (mm) |

92 |

20-77 |

35.2 |

10.4 |

|

Thickness Minimum (mm) |

96 |

3-25 |

7.0 |

3.8 |

|

Thickness Maximum (mm) |

96 |

7-27 |

15.0 |

4.7 |

|

Weight (g) |

96 |

20-243 |

64.7 |

44.5 |

Figure 4. Notched pebbles from Beisamoun - Sub-types: 1-2. Oval; 3-4. Rectangular; 5-6. Trapezoid; 7-8. Rounded.

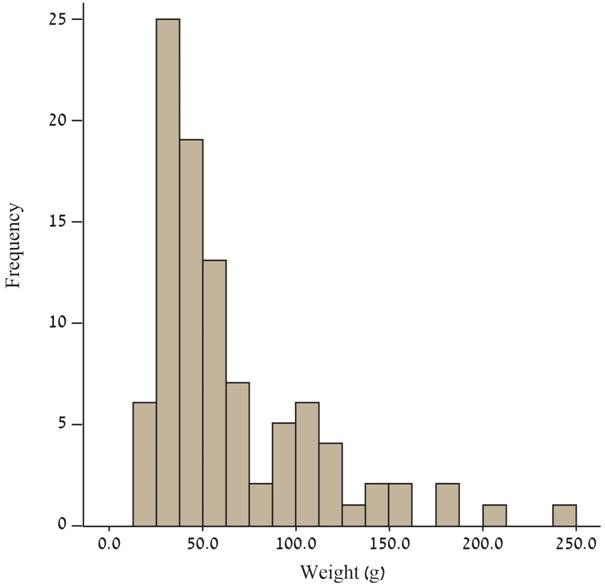

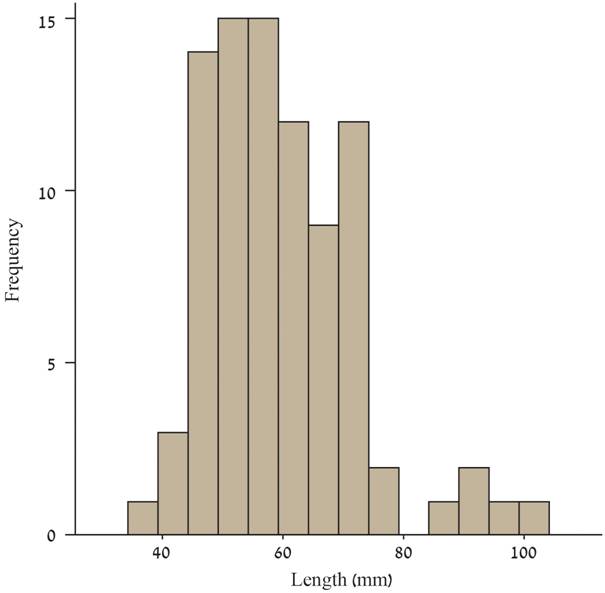

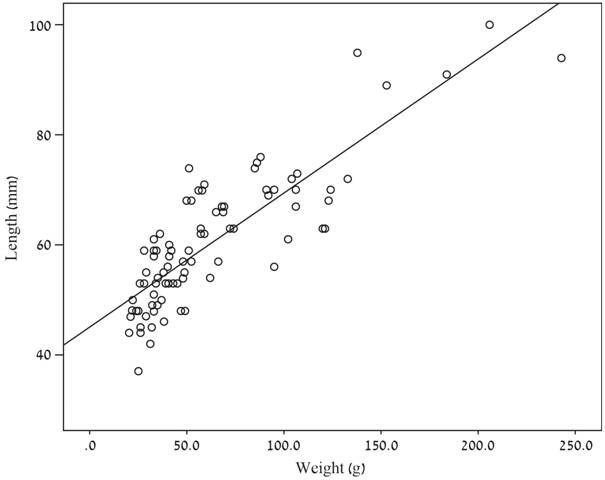

The weights range between 20.0 and 243.0 grams (average = 63.8 g, stdev.= 43.5). As seen in the histogram of Figure 5, there is a moderate bimodality resulting in a number of very large items. Pebble length ranges between 37.0 and 100.0 mm (average=60.2 mm, stdev.=12.2) and have a more uniform distribution then weight ranges, but with a few longer pieces (Figure 6). As expected, length and weight show a strong correlation (Figure 7, r=.848, p=0.00). Width ranges between 20.0 and 90.0 mm (average= 40.0 mm, stdev.=12).

Figure 5. Notched pebbles: histogram of weight.

Figure 6. Notched pebbles: histogram of length.

Figure 7. Notched pebbles: Scattergram of length and weight.

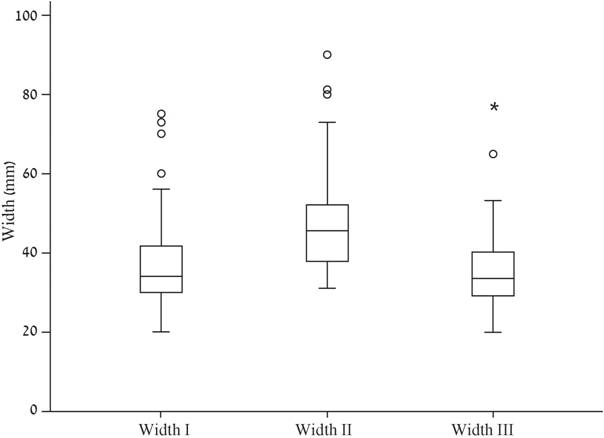

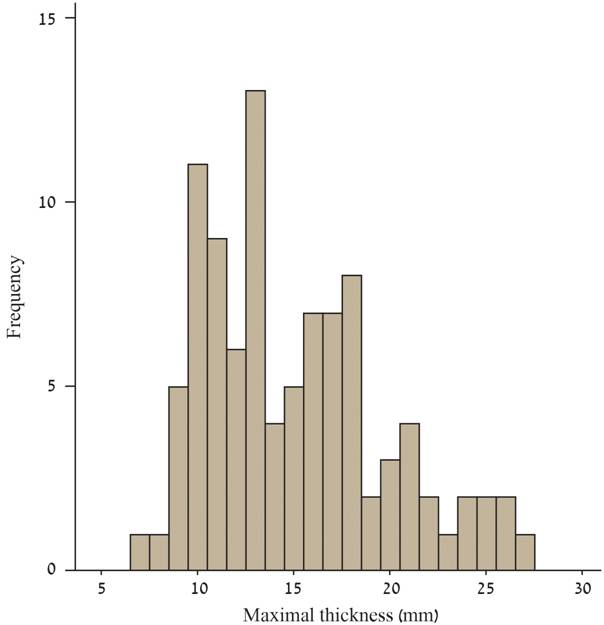

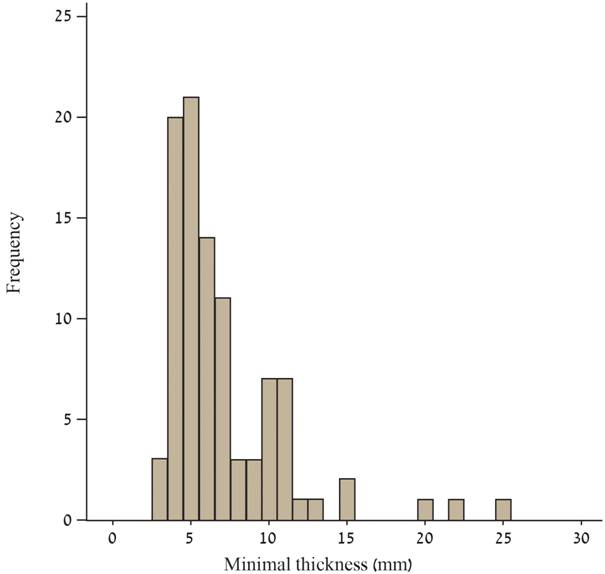

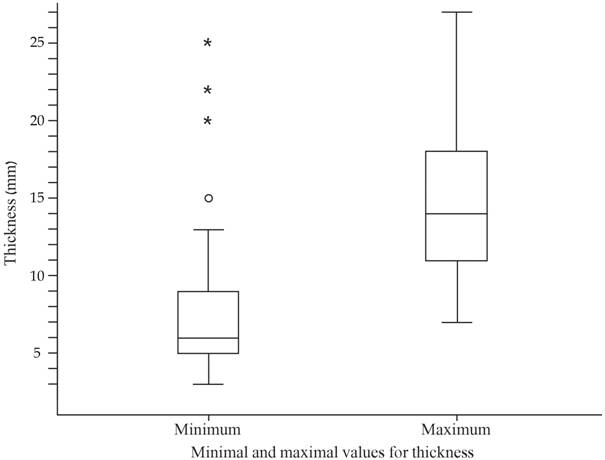

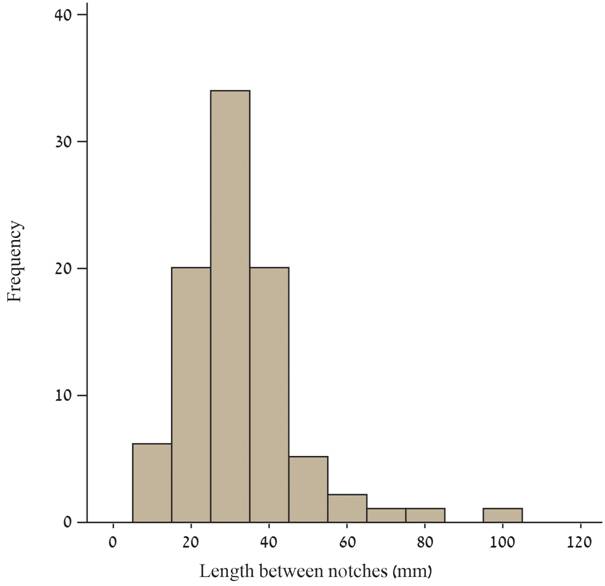

The maximal thickness of most items (Figure 9) is within the 9-18 mm range (average=15.0 mm, stdev.=4.7) and the minimal thickness of most (Figure 10) is within the 4-11 mm range (average= 7.0 mm, stdev.=3.8). The boxplot of Figure 11 indicate that these two measurements vary and this is supported by a t-test that showed a significant difference between them (t=12.87, p= 0.00). This would suggest that thickness was not an overriding factor in the production, even though some thinning was done. The distance between two opposed notches shows a very even distribution (Figure 12), with a range between 31.0 and 91.0 mm (average=55.0 mm, stdev.=10.0).

Width was measured at three points along the long axis of the pebbles, two at each extremity (Width I and III) and at the midpoint of length (Width II). As seen in Table 1, Width II is greater than those of the extremities and this can be seen in the box plots of Figure 8. A one-way analysis of variance (f=34.11, p=0.00) showed that Width II was significantly different from the others. This is the result of the pre-selection of oval pebbles.

Figure 8. Notched pebbles: box plots for width (I and III are at opposite ends while II is in the middle of the items' length).

Figure 9. Notched pebbles: histogram of maximum thickness.

Figure 10. Notched pebbles: histogram of minimum thickness.

Figure 11. Notched pebbles: box plots of minimum and maximum thickness.

Figure 12. Notched pebbles: histogram of distance between two opposed notches.

About 85% of the pebbles were modified (i.e. excluding the production of the notches). In most cases, the modification of the blank consists of flake removal by unifacial or bifacial flaking of most or part of one of the pebble's faces (Figure 13). Usually this preparation encompasses the removal of 3-10 flakes and flaking was directed from the pebble circumference toward it centre. Flake scars are frequently 3-6 mm across. Most of the flakes removed were flat, wide and short, and probably removed less than half of the item’s thickness and probably less than a third of its original weight. It seems that this modification was conducted for the purposes of thinning the weight or for weight reduction (however, it seems that in most cases, the removal of these modification flakes did not drastically change the pebble thickness or weight).

Figure 13. Modification of the pebble faces by flaking.

The notches (Table 2) were mostly produced on the short sides of the pebble (Figure 14). Usually it seems that the notch was made in the middle of the width axis thereby creating two nearly even 'shoulders' from both sides of the notch.

Table 2. Summary of notch attributes.

|

Attribute |

Measured artefacts |

Range |

Average |

St dev |

|

Width of Notch I (mm) |

89 |

5-39 |

13.7 |

5.6 |

|

Width of Notch II (mm) |

82 |

6-31 |

13.4 |

4.9 |

|

Width at shoulders notch I (mm) |

90 |

6-35 |

16.1 |

5 |

|

Width shoulders notch II (mm) |

90 |

5-37 |

15.4 |

5 |

|

Depth of Notch I (mm) |

90 |

1-10 |

3.2 |

1.5 |

|

Depth of Notch II (mm) |

82 |

1-11 |

3.1 |

1.6 |

Figure 14. Notches: production marks.

In terms of production, two clear modes of notch production were discerned: (A) the removal of a single flake (unifacial flaking) accompanied sometimes by delicate pecking, or (B) bifacial flaking. Creating the notches as part of the flaking of one of the pebble faces is also a possibility, although hard to discern. Most notches bear two to four tiny flaking scars. Some notches are V-shaped and some are concave or crescent shaped.

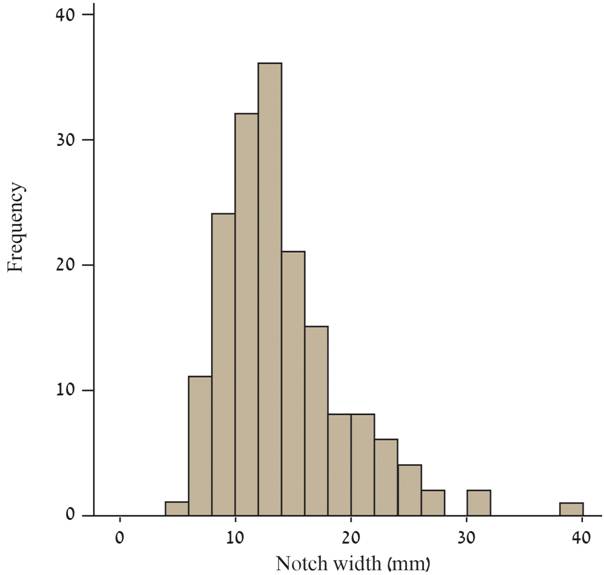

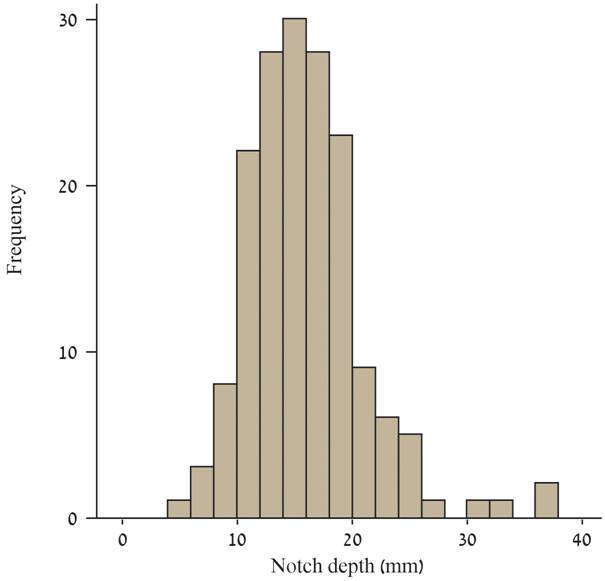

For both notch width and depth, comparisons for each measurement between the two notches were conducted. As no significant differences were found (t=.305, p=.553 for width, t=.595, p=.553 for depth) it was decided to collapse the data from the two notches into a single sample. The values in Table 2 and in Figures 15 and 16 are based on these combined samples.

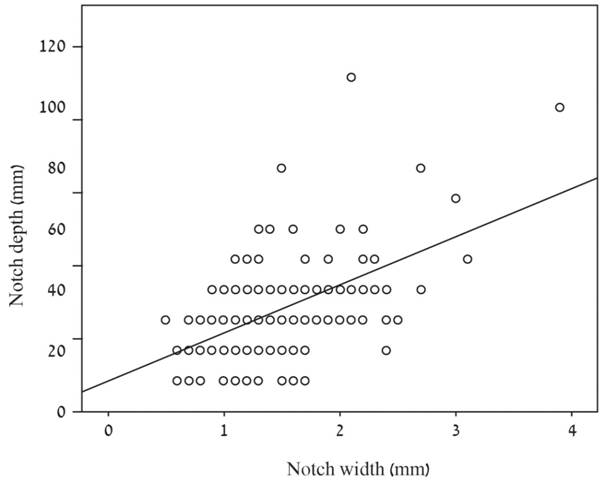

Notch width ranges between 5.0 and 39.0 mm (n=171, average=13.5 mm, stdev.= 5.3 f) with fairly even distribution ( Figure 15). The depth of the notches ranges between 1.0 to 11.0 mm (n=171, average=3.15 mm, stdev.=1.5) again with a uniform distribution (Figure 16). There is a significant, but very weak correlation between notch width and depth (r=.555, p=.00, r2=.31, Figure 17). Shoulder width ranges between 5.0 to 37.0 mm (average=16.0 mm, stdev.=5). In many notched pebbles, clear width and depth metrical similarities were noted between opposed notches on a single pebble. The mean width and depth of the notches suggest a relatively thin cord being tied to the pebble.

Figure 15. Histogram of notch width.

Figure 16. Histogram of notch depth.

Figure 17. Scattergram of notch width and depth.

One of the unusual finds we discovered was that five of the notched weights preserved cord marks or, more probably, the contour of the string (Figure 18). This different “patina” clearly noted here, is so far unique to this assemblage and supplies direct evidence for the use of these items. In two additional examples it was not clear whether the marks are indeed string marks. Interestingly, at least one of these examples shows string marks that do not cross the notches or the axis between them, but cross the pebble length.

Figure 18. String marks on three notched pebbles.

The analysis of the notched pebbles assemblage confirms that several conventions concerning this fresh water fishing gear existed in the Hula Valley during the Neolithic period. These conventions are reflected by specific preferences concerning raw materials, pebble metrics and shape, as well as notch characteristics. Blank modification technique and notch production also reflect the existence of a preferred technological system.

Clear selection of specific blanks made of readily available limestone pebbles most likely originated from the nearby Naphtali Mountains. Basalt that can also be obtained at a short distance (only 2-3 kilometres) from the site was ignored. This means that raw material selection may have been governed first by availability, although technological considerations (the difficulty to modify basalt pebbles compared to limestone pebbles) should also be taken into account.

The notched pebbles show limited variability in terms of shape and, generally speaking, of size and weight as well. Each pebble that was selected to be a notched weight went through some sort of modification. This stage seemingly was dependent on the initial characteristics of the blank (shape, size and, or weight). Flaking is not consistent but bifacial flaking appears to be dominant, probably to create a thinner and slightly lighter item. The results of the attribute analysis show that the size of the notched pebbles and their production answered to fairly well-defined standards that may relate to matters of function and stylistic conventions. Most items were found whole and lacking clear signs of damage or wear.

The data concerning the position, production and size of the notches also suggest conventions that seem to relate not just to the weight but also to the string that was tied around it. The items bearing string marks further confirm that these indeed served as weights. Coupled with the location of Beisamoun near fresh water sources, as other sites with similar items, the identification of these items as fishing weights seems highly probable.

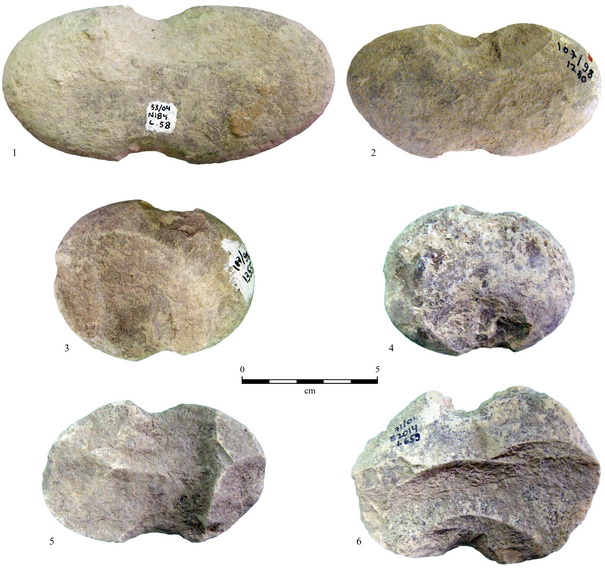

An interesting comparison to the Beisamoun notched weight assemblage comes from the Yarmukian site of Sha‛ar Hagolan, where 36 notched pebbles were found (Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014). The notched pebbles of Sha‛ar Hagolan (Table 3, Figures 19 and 20) are flat and oval and are usually oblate and, more rarely, narrow and elongated. Although most are made of hard limestone, as in the Beisamoun assemblage, a few items made of a softer, chalky limestone were noted as well. Similar to the Beisamoun collection, most are complete (apart from two items). Most cross sections are biconvex or lenticular, retaining the natural outline of the pebble; however, other cross sections were noted as well. As in Beisamoun, the Sha‛ar Hagolan assemblage also displays a limited size range (see Table 3 for comparison); however, weight shows a somewhat wider distribution, with an average of 72.5 g (stdev 31.0).

Table 3. Comparison of notched pebbles from Sha‛ar Hagolan.

|

Attribute |

Sha‛ar Hagolan (n=36) |

Beisamoun (n=97) |

||||

|

|

Range |

Average |

Stdev. |

Range |

Average |

Stdev. |

|

Pebble length (mm) |

58-113 |

74.0 |

10.0 |

37-100 |

60.2 |

11.6 |

|

Pebble width I (mm) |

33-66 |

47.0 |

7.0 |

20-75 |

36.4 |

10.3 |

|

Pebble width III (mm) |

33-58 |

44.0 |

7.0 |

20-77 |

35.6 |

9.7 |

|

Pebble thickness (mm) |

14-32 |

22.0 |

4 |

3-27 |

11.0 |

5.8 |

|

Pebble weight (g) |

30.0-185.0 |

72.5 |

31.0 |

20.0-243.0 |

63.8 |

43.5 |

|

Width of notch I (mm) |

8-52 |

10.0 |

10.0 |

5-39 |

13.6 |

5.5 |

|

Width of notch II (mm) |

7-44 |

18.0 |

7.0 |

6-31 |

13.4 |

54.9 |

|

Depth of notches (mm) |

2-12 |

4.0 |

1.0 |

1-11 |

31 |

1.5 |

Figure 19. Notched pebbles from Sha‛ar Hagolan (after Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014).

Figure 20. Notched pebbles from Sha‛ar Hagolan.

The original pebble modification at Sha‛ar Hagolan also shows some similarities to the technology of weight production at Beisamoun. Contrary to what was noted for the Beisamoun collection, some items exhibited flaking on an entire face; in most of the Sha‛ar Hagolan items (ca. 80% of the assemblage) one or both of the pebble faces were only partly flaked. Additionally, it seems that the flaking was not intended to change the pebble’s outline but rather to thin it or slightly reduce its weight. The number of flake scars seen on the blank faces at Sha‛ar Hagolan varies; some show removal of a single flake while most show 2-4, or more, scars.

An interesting point that separates these two assemblages is the locations (on the long or short side of the pebble) where the notches were carved. While at Beisamoun there is clear preference to produce the notches on the short sides (1-2 exceptions only), at Sha‛ar Hagolan the notches were usually made on the two longer sides of the pebble. In most cases (75%) they were shaped by a series of 5-15 bifacial blows (seemingly reflecting higher investment than in Beisamoun) that removed tiny flakes from both faces (more rarely the notch was formed by a single blow or was retouched). Sha‛ar Hagolan notches show a relatively wide range of maximum width and the depth of the notches also has a considerable range (Table 3). While we can suggest a preferred width and depth for notches in the Beisamoun assemblage, the ranges of the Sha‛ar Hagolan notch width and depth seems to suggest that the most important issue was to create a ‘niche’ in each of the pebble’s sides to accommodate a cord or a rope of a small diameter, while the exact size of the notch was not of great importance.

The picture that emerges from this comparison is that while some aspects clearly point toward resemblance between these two assemblages, in others the correlation is less strong. In both cases however, as seen also in other assemblages in Israel, dated to different periods (Tables 4 and 5), it seems that there is notable intra-site uniformity. This can be seen in the selection of small limestone pebbles (noted in most sites, regardless of period, however see Zaidner & Nadel 2002), and in general the results support the assumption that pebble selection was not random but at least partly dependent on required shape and size (see also Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014).

Table 4. Comparison of notched pebbles assemblages from Israel - Properties. References: 1. Zaidner & Nadel 2002; 2. Marder et al. 2015: 13; 3. Valla et al. 1998: 155-156; 4. Vered & Birkenfeld 2015; 5. This study; 6. Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014; 7. Gopher and Orrelle 1995b; 8. Prausnitz 1970; 9. Zaidner & Nadel 2002; 10. Rosenberg & Greenberg 2014. * No data available.

|

Site |

Period |

N |

Blank |

Raw material |

Notch location |

|

Ohalo II 1 |

Upper Palaeolithic |

47 |

Pebbles |

Basalt, limestone and flint |

Mainly on the long sides |

|

Jordan River Dureijat 2 |

Epipalaeolithic |

1 |

Pebble |

Limestone |

On the long sides (uncertain) |

|

Eynan 3 |

Epipalaeolithic, Natufian |

6 |

Pebbles |

Limestone |

On the long sides (uncertain) |

|

Ain Dishna 4 |

PPNA |

* |

Pebbles |

Basalt, limestone |

On the long sides |

|

Beisamoun 5 |

PPNB-PN |

96 |

Pebbles |

Mainly limestone |

On the short sides |

|

Sha'ar Hagolan 6 |

Pottery Neolithic, Yarmukian |

36 |

Pebbles |

Mainly limestone |

Mainly on the long sides |

|

Munhata 7 |

PN (uncertain) |

3 |

* |

Basalt, limestone |

Mainly on the long sides |

|

Tel Ali 8 |

PN (uncertain) |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Ha'on 9 |

(uncertain) |

55 |

Pebbles |

* |

Mainly on the long sides |

|

Tel Beit Yerah 10 |

Early Bronze Age |

12 |

Pebbles |

Limestone |

Mainly on the long sides (uncertain) |

Table 5. Comparison of notched pebbles assemblages from Israel - sizes and weights. References: 1. Zaidner & Nadel 2002; 2. Marder et al. 2015: 13; 3. Valla et al. 1998: 155-156; 4. Vered & Birkenfeld 2015; 5. This study; 6. Rosenberg & Garfinkel 2014; 7. Gopher and Orrelle 1995b; 8. Prausnitz 1970; 9. Zaidner & Nadel 2002; 10. Rosenberg & Greenberg 2014. * No data available.

|

Site |

Period |

N |

Average of maximum length (mm) |

Average of maximum width (mm) |

Average of maximum thickness (mm) |

Average Weight (g) |

|

Ohalo II 1 |

Upper Palaeolithic |

47 |

109 |

84 |

36 |

344 |

|

Jordan River Dureijat 2 |

Epipalaeolithic |

1 |

107 |

52 |

22 |

* |

|

Eynan3 |

Epipalaeolithic, Natufian |

6 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Ain Dishna 4 |

PPNA |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Beisamoun 5 |

PPNB-PN |

96 |

60 |

40 |

11 |

63 |

|

Sha'ar Hagolan 6 |

Pottery Neolithic, Yarmukian |

36 |

74 |

47-44 |

22 |

72.5 |

|

Munhata 7 |

PN (uncertain) |

3 |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Tel Ali 8 |

PN (uncertain) |

* |

* |

* |

* |

* |

|

Ha'on 9 |

(uncertain) |

55 |

94 |

68 |

33 |

277 |

|

Tel Beit Yerah 10 |

Early Bronze Age |

12 |

6.2 (max) |

5 (max) |

2.5 (max) |

71 (max) |

We can see similarities in pebble modification as well as in notch production and size (width and depth), but some variability is notable. In most cases, a given assemblage seems to reflect a clear preference for producing the notches on either the long or short sides. In fact, the Beisamoun assemblage seems to reflect a different pattern from most known assemblages because of the preference for notching on the short sides (Table 4).

In summary, fresh water fishing (as opposed to fishing in the Mediterranean Sea, which has its own characteristics, see Galili et al. 2004) with ‘throwing nets' or with fishing lines or rods using notched pebbles persisted in much the same manner for a long period of time in the northern Jordan Valley. This fishing gear was apparently first used by Upper Palaeolithic and later complex Epipalaeolithic hunting and gatherers, but continued in use by sedentary Neolithic communities that practiced an economy based on domesticated plants and animals, as well as by early urban societies. This suggests the continued existence of fishing traditions along the Jordan Valley and that fishing was an important component in the economy of communities living near fresh water sources in this area. Although they appear minor at first sight, small differences in the form of the weights, their sizes and the location and size of the notches may indicate varying fishing methods, probably related to the tying of the weight.

As demonstrated above, the notched weight assemblage of Beisamoun offers a great opportunity to test conventions in fresh water fishing gear. Indeed, our analysis shows that such preferences did exist. The significance of this assemblage however, lies not just in its size, but also supplies the first evidence for characteristics of the string that was used to tie the weight (possibly a fishing line). With additional data gathered in the coming years from new assemblages, it will be possible to test, on a larger scale, some of the suggestions raised here concerning long-term conventions in fishing gear in the southern Levant.

This paper is dedicated to Ammnon Asaf, a friend and colleague with a true passion for archaeology and the prehistory of the Hula Basin. We would like to thank A. Regev for graphic assistance and E. Gershtein for photography.

Altman, H. M., & Ebrary, I. 2006, Eastern Cherokee Fishing. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, 168 p.

Bar-Yosef, O. 1998, The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6(5): 159-177. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:5%3C159::aid-evan4%3E3.0.co;2-7

Bar-Yosef, O., & Belfer-Cohen, A. 1989, The origins of sedentism and farming communities in the Levant. Journal of World Prehistory, 3(4):447-498. doi:10.1007/bf00975111

Bocquentin, F., Khalaily, H., Bar-Yosef Mayer, D., Berna, F., Biton, R., Boness, D., Dubreuil, L., Emery-Barbier, A., Greenberg, H., Goren, Y., Horwitz, L. K., Le Dosseur, G., Lernau, O., Mienis, H. K., Valentin, B., & Samuelian, N. 2014, Renewed excavations at Beisamoun: Investigating the 7th millennium cal. BC of the Southern Levant. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 44: 5-100

Bocquentin, F., Khalaily, H., Samuel, N., Barzilai, O., Le Dosseur, G., Horwitz, L. K., & Barbier, A. E. 2007, Renewed excavation of the PPNB Site of Beisamoun, Hula Basin. Neo-Lithics, 2(7): 17-21.

de Contenson, H. 1992, Préhistoire de Ras Shamra: Text, Figures et Planches: Ras Shamra-Ougarit VIII, Vol. 1 and 2. Éditions Recherche sur les civilisations, Paris, 285 p.

Galili, A., Lernau, O., & Zohar, I. 2004, Fishing and coastal adaptation at Atlit-Yam - A submerge PPNC fishing village off the Carmel coast, Israel. ‘Atiqot, 48: 1-34.

Galili, E., Rosen, B., Gopher, A., & Kolska-Horwitz, L. 2003, The emergence and dispersion of the Mediterranean fishing village: Evidence from submerged Neolithic settlements off the Carmel Coast, Israel. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology, 15:167-198. doi:10.1558/jmea.v15i2.167

Gopher A., & Orrelle E. 1995a, The Ground Stone Assemblages of Munhata. Cahiers des Missions Archéologiques Françaises en Israël 7, Faton, Paris, 183 p.

Gopher, A., & Orrelle, E. 1995b, The Ground Stone Assemblages of Munhata: A Neolithic Site in the Jordan Valley, Israel: a Report. Les Cahiers Des Missions Archéologiques Françaises En Israël Vol. 7. Association Paléorient, Paris, 183 p.

Khalaily, H., Barzilai, O., & Jaffe, G. 2009, Beisamoun (Mallaha). IAA Reports 121, Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem. URL: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/report_detail_eng.asp?id=1245&mag_id=115

Khalaily, H., Kuperman, T., Marom, N., Milevski, I., & Yegorov, D. 2015, Beisamun: An Early Pottery Neolithic site in the Hula Basin. ‘Atiqot, 82: 1-61.

Lechevallier, M. 1978, Abou Gosh et Beisamoun: Deux Gisements du VII Millénaire Avant L’ère Chrétiènne en Israël. Mémoires et Travaux du Centre de Recherches Préhistoriques Francais de Jérusalem Vol. 2, Paris, 289 p.

Marder, O., Biton, R., Boaretto, E., Feibel, C., Melamed, Y., Mienis, H. K., Rabinovich, R., Zohar I. & Sharon, G. 2015, Jordan River Dureijat - A new Epipalaeolithic site in the Upper Jordan Valley. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 45: 5-30.

Moore, A. M. T. 2000, Stone and other artifacts. In: Village on the Euphrates: From Foraging to Farming at Abu Hureyra, (Moore, A.M.T., Hillman, G.C., & Legge, A.J., Eds.), Oxford University Press, Oxford: p. 165-186.

Nadel, D., & Zaidner, Y. 2002, Upper Pleistocene and Mid-Holocene net sinkers from the Sea of Galilee, Israel. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 32: 49-71.

Pajdla, P. 2014, Overview of Prehistoric Tools Connected with Fishing in the Upper Mesopotamia. Unpublished Master of Arts Thesis, Masaryk University, Brno, 56 p.

Perrot, J. 1966, Le gisement Natufien de Mallaha (Eynan), Israël. L’Anthropologie, 70(5-6): 437-484 (in French) (“The Natufian settlement from Mallaha (Eynan), Israël”)

Perrot, J. 1975, בייסמון בעמק החולה, Qadmoniot: A Journal for the Antiquities of Eretz-Israel and Bible Lands, 4(32): 114-117 (in Hebrew) (“Beisamoun in the Hula Valley”). URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23671628

Potts, D. T. 2012, Fish and fishing. In: A Companion to the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, (Potts, D. T., Ed.), John Wiley & Sons, Chichester: p. 220-235. doi:10.1002/9781444360790.ch12

Prausnitz, M.W. 1970, From Hunter to Farmer and Trader: Studies in the Lithic Industries of Israel and Adjacent Countries (From the Mesolithic to the Chalcolithic Age). Sivan Press, Jerusalem, 184 p.

Rau, C. 1884, Prehistoric Fishing in Europe and North America. Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C, 380 p. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.29980

Rosenberg, D. 2010, An Early Pottery Neolithic Occurrence at Beisamoun, the Hula Valley, Northern Israel. BAR International Series Vol. 2095, Archaeopress, Oxford, 138 p.

Rosenberg, D. 2011, התפתחות, המשכיות ושינוי: תעשיות האבן בתרבויות הקרמיות המוקדמות בדרום הלבאנט. Ph.D. thesis, University of Haifa, Haifa, 572 p. (in Hebrew) (“Development, continuity and change: the stone industries of the early ceramic-bearing cultures of the Southern Levant”)

Rosenberg, D., Assaf, A., Eyal, R., & Gopher, A. 2006, Beisamoun - The Wadi Raba occurrence. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 36: 129-137.

Rosenberg, D., & Garfinkel, Y. 2014, Sha’ar Hagolan 4 - The Groundstone Industry: Stone Working at the Dawn of Pottery Production in the Southern Levant. The Institute of Archaeology, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, 336 p.

Rosenberg, D., & Greenberg, R. 2014, The stone assemblages. In: Bet Yerah: The Early Bronze Age Mound (Vol. 2) Urban Structure and Material Culture. 1933-1986 Excavations, (Greenberg, R., Ed.), IAA Reports Vol. 54, Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem: p. 189-234.

Sandelowski, B. H. 1970, Notched pebbles from South Africa. South Africa Archaeological Bulletin, 26(103/104): 154. doi:10.2307/3887810

Smith, H. I. 1910, The Archaeology of the Yakima Valley. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History. Vol. 4, Part 1. American Museum of Natural History, New York, 470 p.

Valla, F. R., Khalaily, H., Samuelian, N., Bocquentin, F., Delage, C., Valentin, B., Plisson, H., Rabinovich, R., & Belfer-Cohen, A. 1998, Le Natufien Final et les nouvelles fouilles à Mallaha (Eynan), Israel 1996-1997. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 28: 105-176.

Vered, A., & Birkenfeld, M. 2015, Notched Stone Weights from PPNA ʻEin Dishna: a Longue Durée Perspective. A poster presented in the first meeting of the Association for Ground stone Tools Research (AGSR), July 5-9, 2015. University of Haifa, Haifa.

Yegorov, D. 2011, Flint Industry from Beisamoun and the Question of Yarmukian Settlement in the Hula Valley. Unpublished MA Thesis, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer Sheva, 82 p.

Zaidner, Y. 2002, Double-notched pebbles from Ohalo II: The earliest evidence for the use of net sinkers in the Levant. In: Ohalo II: A 23,000 Year-Old Fisher-Hunter-Gatherers’ Camp on the Shore of the Sea of Galilee, (Nadel, D., Ed), Reuben and Edith Hecth Museum, University of Haifa, Haifa: p. 49-52

Zohar, I., Goren, M., & Goren-Inbar, N. 2014, Fish and ancient lakes in the Dead Sea Rift: The use of fish remains to reconstruct the ichthyofauna of paleo-Lake Hula. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 405: 28-41. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2014.04.006