The function of Early Natufian grooved basalt artefacts from el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel: Preliminary results of a use-wear analysis

1. The Use-Wear Analysis Laboratory, The Zinman Institute of

Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. Email:

usewear@research.haifa.ac.il

2. Laboratory for Ground Stone Tools Research, The Zinman Institute of

Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel. Email:

drosenberg@research.haifa.ac.il

3. The Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel.

Email: Yeshurun: ryeshuru@research.haifa.ac.il;

Kaufman: dkaufman@research.haifa.ac.il;

Weinstein‑Evron: evron@research.haifa.ac.il

Grooved items are usually regarded as tools used for modifying other implements made of bone, stone, plants or wood, whether referred to as shaft straighteners, smoothers, polishers or sharpening tools. They were also attributed to various symbolic meanings in Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in the southern Levant and they were also associated with bead manufacturing process in the Neolithic. Grooved basalts found on Early Natufian (ca. 14,000 BP) living floors at el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel, were the subject of microscopic use-wear analysis. Here we present the preliminary results of the research, introducing our functional reconstruction based on experiments. The most outstanding result is that traces on the perimeters, attributed to shaping of the artefact, are different from the traces inside the groove which are related to the use of the artefact. We conclude that the groove is a part of the instrument, shaped before its use in order to work the abraded materials. Traces indicate that the shaping of the perimeters was done by abrasion against a very hard rock, probably using water to enhance the smoothing of the stone. Traces inside the groove indicate, as was previously assumed for these artefacts, that the groove was used as a shaft straightener. However, traces also indicate that the groove was used to abrade different types of materials which might not be related to the preparation of shafts including reeds, wood, and especially minerals such as ochre. Our preliminary results indicate the multi-functional nature of these items shedding light on their production, use and discard history.

Keywords: shaft straighteners; el-Wad Terrace; Natufian; use-wear analysis; multi-functional tools; ground stone tools

The Natufian culture of the terminal Pleistocene, Late Epipaleolithic Levant (ca. 15,000-11,700 cal. BP) is widely thought to reflect a sedentary hunter-gatherer adaptation on the threshold of agriculture (e.g., Garrod 1957; Perrot 1966; Valla 1995; Bar-Yosef 1998; Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef 2002). This view is based on the appearance of large sites with durable architecture and hewn bedrock features, rich ground stone and bone industries and artistic repertoire, evidence for economic intensification, the presence of commensal animals, and cemeteries exhibiting elaborate burial customs.

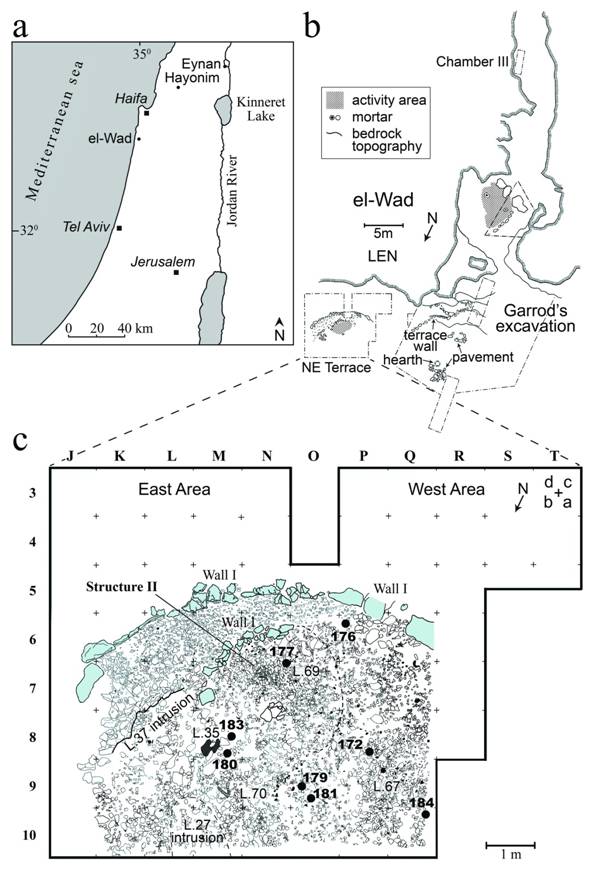

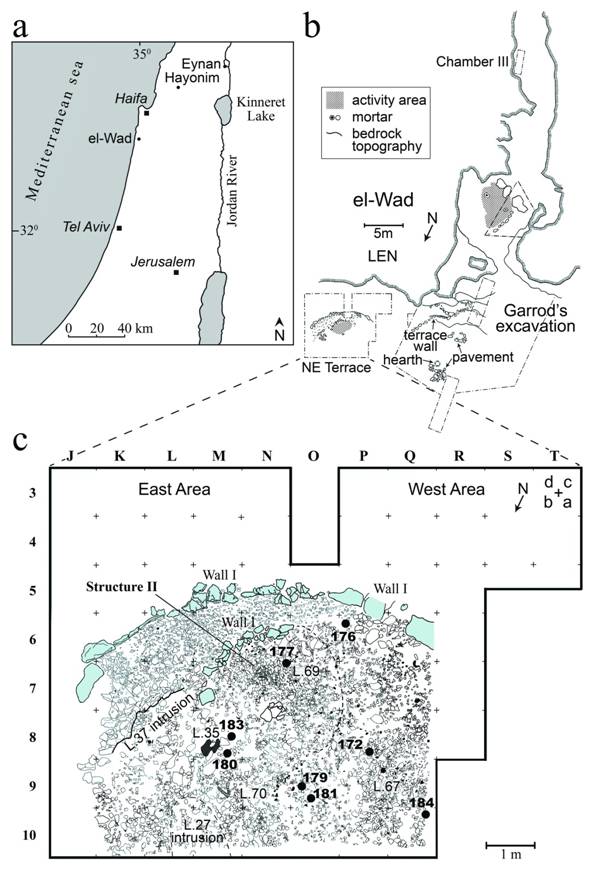

El-Wad is situated on the western face of Mount Carmel (Israel) where the cliff of the mountain meets the open expanses of the Mediterranean coastal plain, 45 m above modern sea level within the Mediterranean climate zone of the Levant (Figure 1a). The site was first investigated by C. Lambert in 1928 (Weinstein-Evron 2009: Chapter 2), but became well-known as a result of D. Garrod’s 1929-1933 excavation campaign (Garrod & Bate 1937). The terrace was later revisited (Valla et al. 1986) as was the cave (Weinstein-Evron 1998: Chapter 5).

Recent excavations focus on the north eastern part of the terrace (Figure 1b), where an area of ca. 70 m2 has been exposed, yielding Natufian sediments between 0.5 and 1.5 m thick incorporating all Natufian phases (Weinstein-Evron et al. 2007; 2012; Kaufman et al. 2015). A composite stratigraphy of the entire site (Weinstein-Evron 2009: 63-70; Weinstein-Evron et al. 2013: 1332-1337) suggests an ephemeral occupation at the base of the Early Natufian (EN), followed by a prolific burial phase containing almost 100 individuals, and culminating with the Late Early Natufian (LEN). The latter is the main EN layer of the site, characterized by varied architectural features (Figure 1c). In the recent NE Terrace excavation the LEN phase appears as a massive, > 0.5 m thick accumulation of repeated occupations. Overlying this architectural phase are thick EN living levels with a few stone-built features, but generally lacking structures. The sequence ends with a thin Late Natufian, and perhaps Final Natufian layer, devoid of architecture but displaying several concentrations of graves.

The renewed excavation exposed a LEN architectural complex (Figure 1c) delineated by a 9-meter long curvilinear “terrace wall” (Wall I) encompassing a sequence of at least nine architectural sub-phases, each defined by a thin stony floor, some of which abut a smaller stone wall (Wall II). The stony floors are well-defined laterally by the adjacent stone-poor matrix, and also vertically, separated by stone-poor sediment (see Yeshurun et al. 2013; 2014a). The series of stony floors and between-floor sediments are interpreted as dwelling interiors, while the stone less matrix lying north of this series is interpreted as having been outside of the dwelling (but still within the area delimited by the large terrace wall). In addition to these internal or external dwelling accumulations, a large pile of stones incorporating a seemingly burned matrix and concentrations of lithics (Locus 67) was found just northwest of the area of Structure II (Figure 1c). The LEN architectural features were dated by radiocarbon measurements on charcoals and ungulate bones to yield a calibrated age range of 14,660-14,030 cal. BP (±1σ: Eckmeier et al. 2012; Weinstein-Evron et al. 2012).

Human remains are virtually absent in these phases, but the density of other finds is very high, specifically chipped lithic and ground stone tools, bone tools, bone and shell ornaments, ochre, and a large faunal assemblage (Rosenberg et al. 2012; Weissbrod et al. 2012; Yeshurun et al. 2013; 2014b). The stone structures, numerous living floors, density and diversity of finds and the absence of burials indicate that this part of the site was intensively used for daily activities during at least parts of the EN.

Figure 1. a) Map showing the location of the site of el-Wad, b) plan of el-Wad showing the cave and terrace, c) detailed plan of el-Wad terrace showing architectural features and location of the grooved basalts studied for use-wear analysis.

Natufian ground stone assemblages, richer and more numerous than those of any previous prehistoric sequence of the Levant, reflect significant social and economic changes of hunter-gatherers shifting toward a sedentary way of life (e.g., Bar-Yosef 1983; Wright 1991; 1994). As such, they have been the subject of much research concerning various aspects such as typological and morphological variability, technology of production, functional studies and raw material provenance determination, thereby contributing greatly to our understanding of Natufian economic and social activities (e.g., Perrot 1966; Belfer-Cohen 1988; Wright 1991; 1994; Samzun 1994; Weinstein-Evron et al. 1995; 1999; 2001; Dubreuil 2004; Hardy-Smith & Edwards 2004; Eitam 2008; Dubreuil & Grosman 2009; Nadel & Lengyel 2009; Valla 2009; Nadel & Rosenberg 2010; Rosenberg & Nadel 2011; Rosenberg et al. 2012; Valla 2012; Edwards 2013; Edwards & Webb 2013; Hayden et al. 2013; Rosenberg 2013; Rosenberg & Nadel 2014; Nadel et al. 2015).

The changes that characterize Natufian ground stone assemblages include a dramatic rise in overall tool frequencies, typological and stylistic variations, specific raw material selection as well as changes in contextual and discard patterns. Developments were noted for the technological apparatus of tool production and production sequences (Wright 1991; 1994). The most common components of Natufian stone assemblages are pestles followed by bowls and mortars, bedrock features, grinding stones, grooved and perforated items. These tools are frequently made of basalt or limestone (other raw materials are present as well). Natufian ground stone tools and bedrock features are found in Natufian base camps, temporary camps and mortuary sites and in a variety of contexts - indoors, incorporated in building construction, near structures, as well as in grave structures and fills.

An analysis of the entire ground stone assemblage of el-Wad Terrace was recently published (Rosenberg et al. 2012) adding to other studies that dealt with ground stone assemblages from previous excavations at the site (Garrod & Bate 1937: 10; Valla et al. 1986; Weinstein-Evron 1998: 96-98).

The assemblage is one of the largest Natufian ground stone assemblages presently known (n=565). Most of the items were retrieved from the EN layer (n=335, 59.3% of the assemblage) while only a few (n=30, 5.3% of the assemblage) were found in a clear LN context. The remaining implements are divided between items found in stratigraphic units defined as transitional or undetermined EN or LN (n=75, 13.3% of the assemblage), in ill-defined contexts, or on the site’s surface (n=125, 22.1% of the assemblage). The assemblage from the renewed excavations at el-Wad Terrace (Rosenberg et al. 2012) is dominated by pestles and also includes lower and upper grinding stones, vessels and mortars of various sizes, ‘bowlets’, weights and other tools classified as varia and unidentified fragments. One of the notable finds here is a large collection of grooved pebbles and recycled tools (mainly pestles) that are presented herein.

Grooved stones are reported occasionally from several sites in Europe predating the period of the Natufian culture of the southern Levant (de Beaune 1993). The single grooved stone from Hayonim Cave (Stratum D) is the only example found in the southern Levant predating the Natufian culture (Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef 1981: 34, Fig. 7: 4). Only during the Natufian do grooved stones become an outstanding component of the ground stone tool kit.

Grooved items made on pebble-like stones and modified artefacts (in secondary use) are usually regarded as tools used for shaping or modifying other implements made of bone, stone, plants or wood, whether referred to as shaft straighteners, smoothers or polishers, sharpening tools or others (Hole et al. 1969: 196; Solecki & Solecki 1970: 838; Bar-Yosef 1983; Voigt 1983; Adams 2002: 82-91; Wilke & Quintero 2009; Rosenberg 2011:138-139). Since the cross-section and length of the grooves are of special significance for the reconstruction of function, these attributes are frequently used in typological classification (Rosenberg 2011: 138-139; Vered 2013). Previous studies have attributed various symbolic meanings to the grooved items from Neolithic and Chalcolithic sites in the southern Levant and linked them with the realms of cult and magic (Stekelis 1972: 36; Gopher & Orrelle 1996; Hermansen 1997; Cauvin 2000: 48). Recently it has been claimed that similar items were part of the bead manufacturing process in the Neolithic (Wright et al. 2008: Fig. 5: c).

The grooved stone assemblage of el-Wad Terrace is one of the largest known (n=17) dated to the Natufian. The eight grooved items under study, retrieved from the two lowermost phases (W-6 and W-7) of the LEN layer, are associated with building remains. The remaining items, which are not discussed here, came from an EN or LN context (n=1), from a LN context (n=1), or from unclear provenances. All eight items that were studied for the presence of distinctive use-wear were found within the Wall I complex. Additionally, all but one (#177) were found outside of the Structure II area (Figure 1c and Table 1).

Table 1: The EN Unit 2 grooved basalts for this study and their provenience information.

|

EWT Cat# |

Square |

Context |

|

172 |

P8a |

Surface outside Structure II, adjacent to top of stone heap (Locus 67) |

|

176 |

P6d |

Just outside Structure II |

|

177 |

N7c |

Inside Structure II |

|

179 |

O9b |

Outside Structure II |

|

180 |

M8a |

Outside Structure II |

|

181 |

O9b |

Outside Structure II |

|

183 |

M7a |

Outside Structure II |

|

184 |

Q10c |

Outside Structure II, above Locus 67 |

The eight EN items were made from compact basalt (see below). They are all broken. Six of these are oval pebble-like stones of various sizes and two artefacts are reused pestles (items #171 and #180) that were turned into groove-bearing items. In this paper we present the preliminary results of the microscopic analysis of the grooved basalts with the aim to reconstruct their function by the application of a use-wear analysis methodological framework. Results will be introduced for six of the items as research is at its initial stage of analysis. The two remaining items are still covered with calcareous crust which we chose not to remove at this point.

Use-wear analysis of ground stone tools has advanced considerably in the last few years due to the growing interest in reconstructing their function, especially in the field of standardizing the recording procedures and terminology (for example, Adams et al. 2009; Dubreuil & Savage 2013). In parallel, Levantine Natufian ground stone tools were occasionally subjected to use-wear analyses (Dubreuil 2002; 2004; 2008; Dubreuil & Grosman 2009; 2013; Savage 2014). These analyses yielded valuable results in terms of analytical procedures and revealing aspects of human activities. In our research we focus on a specific type of tool, the grooved stones, specifically those shaped on basalts exhibiting U-shaped grooves running along one axis of the stone. Our aim in this research is to reconstruct the function of the grooved basalts in their Natufian context at the site of el-Wad Terrace. We focus on use-wear produced through friction with the aim of reconstructing the mode by which the grooves were formed and used based on experiments.

The grooved basalts were observed in a systematic order, integrating low power observations with a stereomicroscope (Nikon SMZ 745T, magnification up to x50) and high power observations with a metallographic microscope (Leica DM 1750 M, magnifications up to x500). Traces were documented using the microscope camera and focus-stacking was used to produce fully focused photographs especially for surfaces photographed in high magnification (using Helicon Focus© or the LAS V4.1 program installed to process photographs from the metallographic microscope).

Observations were taken in a consistent order, first along the bottom of the groove, then on the walls of the groove and finally on the surfaces away from the groove. This was done firstly to identify traces according to their location on the artefact, and accordingly, to distinguish different wear patterns resulting from manufacturing procedures or utilization. Natural surfaces, those appearing on breaks, were also observed in order to study the characteristics of the basalts and the alterations resulting from post depositional process. These were compared to the modified (by production or by utilization) surfaces.

For the experimental tools, observations were aimed at studying the natural properties of the basalt, and then at distinguishing wear-traces on the macro and micro scale. Our experimental program included different levels of analysis, but at this stage we have accomplished a limited set from which the results were used for our preliminary reconstruction. At this point we studied different wear patterns produced on compact basalt fragments collected from basaltic outcrops in the Lower Galilee, northern Israel. These basalts resemble the properties of the archaeological artefacts, and are considered as one of the possible sources of basalts worked at el-Wad Terrace (Weinstein-Evron et al. 1999). In our experiments we abraded the basalt fragments against various types of materials, including basalt, limestone, travertine, coastal aeolianite ('kurkar'), wood and reeds (some of the experiments and resulting use-wear are presented in Figure 2). For the current report, we have analysed the different wear patterns, isolated from any other intentional alterations, and used them to interpret the traces observed on the archaeological tools. The characterization of the traces was done based on the descriptive systems proposed by Adams et al. (2009) and Dubreuil & Savage (2013) and the results accomplished at this stage were used to infer the broad functional reconstruction for the archaeological artefacts.

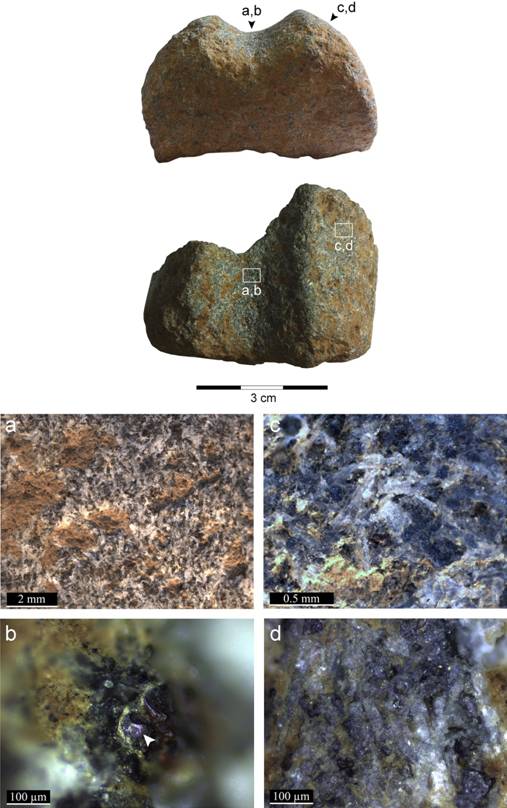

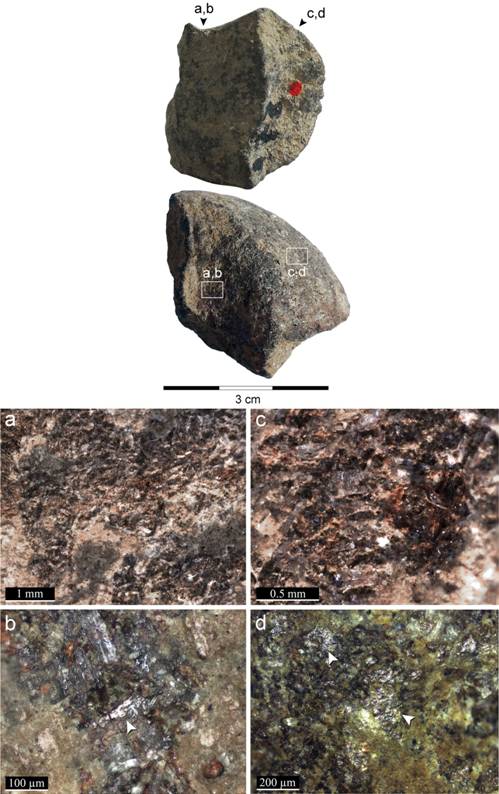

The grooved items are made of compact basalts and all are broken on one or more faces. The main attribute of the studied sample is the single U-shaped groove characterized by a rounded bottom and walls expanding outwards and smoothed surfaces on the perimeters (Figures 3-8). When possible, the dimensions of the grooves were measured, exhibiting a wide range of depths (between 5 and 12 mm) and relative consistency of maximum width (16-20 mm).

Figure 2: Photos of some of the experiments conducted and wear patterns observed on the experimental pieces: a) abrasion against a piece of bone, b) coastal aeolianite or 'Kurkar', c) wood log, d) abrasion with flint, e) flat surface exhibiting large pits with abrupt edges and unmodified bottom produced by abrasion against basalt for 30 minutes (original magnification x20), f) rough but levelled surface with multiple shallow grooves indicating the direction of abrasion produced by abrasion against travertine for 30 minutes (original magnification x20), g) flat surface with heavily striated micro-polish indicating the direction of abrasion developed on protruding surfaces of the basalt produced by abrasion against ‘kurkar’ for 60 minutes (original magnification x200), h) bright domed micro-polish developed on protruding points of the basalt produced by the abrasion against a wood log for 30 minutes (original magnification x200).

The most outstanding observation in the analysis of the grooved basalts is that traces observed outside the groove (the perimeters) are different from the traces observed inside the groove. Our basic assumption is that traces outside the groove might reflect the manufacturing of the instrument, focusing on distinguishing them from surfaces characteristic to natural surfaces or rolled pebble stones, and traces inside the groove reflect its use, focusing on the comparison to the experimental pieces to reconstruct their function (Table 2).

Table 2: Summary of use-wear analysis results with details of the wear characteristics and the inferred functions.

|

# |

Perimeters |

Inside groove |

Figure |

||

|

|

Traces |

Interpretation |

Traces |

Interpretation |

|

|

Flat peaks with sharp edges, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Abrasion against extremely hard stone (and probably water) |

Flat peaks, flattening extending into pits, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of wood or bone |

3 |

|

|

172 |

Flat peaks with sharp edges, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Abrasion against a hard stone (and probably water) |

Flat peaks, flattening extending into pits, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of wood or bone |

4 |

|

176 |

Levelled granular rough surface |

Abrasion against a hard stone |

Slight blackening, shallow cracks, wide flat surface associated with large pits and shallow grooves, patches of micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of wood, bone or reeds; application of heat |

5 |

|

177 |

Wide flat peaks, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Abrasion against a hard stone |

Wide flat surface, shallow grooves, patches of micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of wood, bone or reeds |

6 |

|

180 |

Levelled granular rough surface |

Abrasion against a hard stone (and probably water) |

Blackening, extremely flat surface, numerous pits, micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of wood, bone or reeds; application of heat |

7 |

|

181 |

Levelled granular rough surface, and an area with crushing |

Abrasion against a hard stone, and crushing minerals such as ochre |

Blackening, shallow cracks, extremely flat surface, micro-polish |

Back and forth abrasion of a mineral; application of heat |

8 |

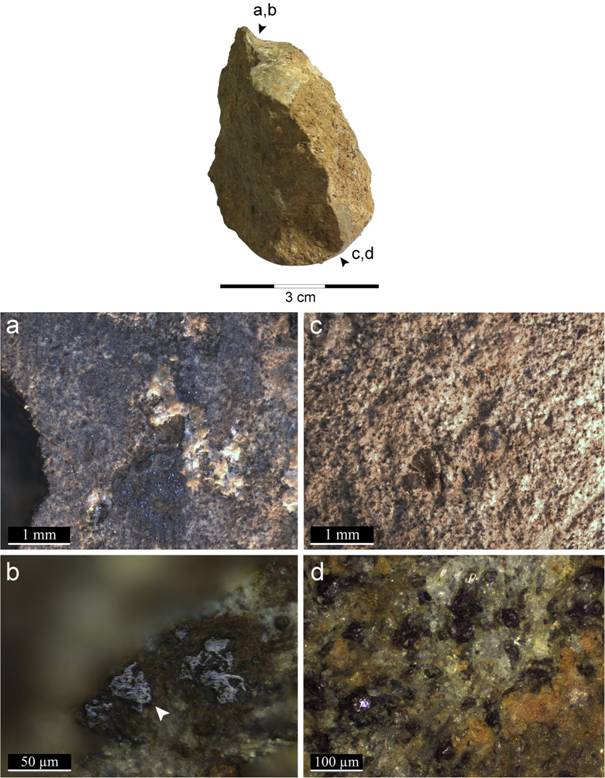

Figure 3: Artefact number 171 is a broken pestle on which a groove was shaped. The groove has a concave bottom and walls extending outward. Locations of micrographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove interpreted as having been produced by contact with medium hardness material such as bone or wood: a) flat peaks with flattening extending into the lower surfaces (x6.7), b) micro-polish developed on protruding surface indicated by the white arrow (x200). Traces on the perimeters interpreted to be produced by contact with a hard stone: c) extremely flat peaks with sharp edges and few remnants of lower areas (x50), d) thin and transparent polish spreading on the wide surface of the basalt (x200).

Figure 4: Artefact number 172 with a side view showing the concave bottom of the groove and walls extending outward. Locations of microphotographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove interpreted as having been produced by contact with medium hardness material such as bone or wood: a) flat peaks with flattening extending into the lower surfaces indicating contact with medium hardness material such as bone, wood or reeds (x20), b) micro-polish developed on protruding surface indicated by the white arrow showing directionality pattern parallel to the main axis of the groove (x200). Traces on the perimeters interpreted as having been produced by the contact with a hard stone: c) extremely flat peaks with sharp edges (x50), d) rough bright polish developed on protruding points indicated by the white arrows (x100).

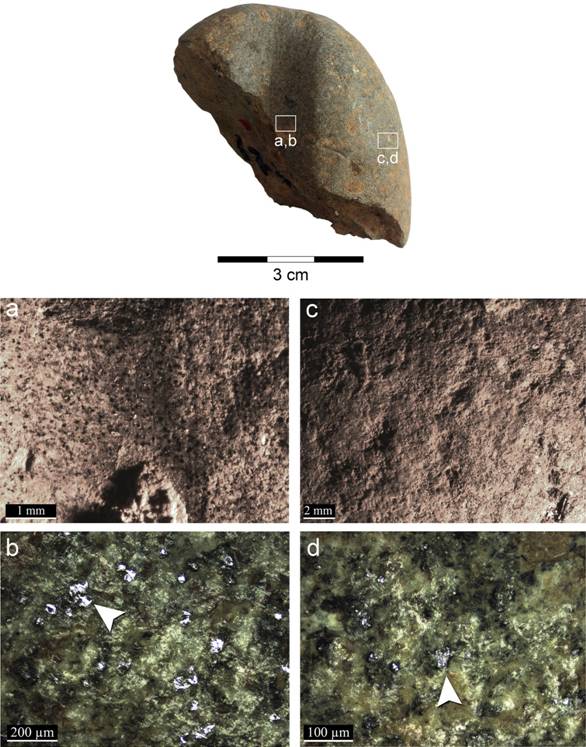

Figure 5: Side view of artefact number 176 showing the concave bottom of the groove and walls extending outward. Locations of microphotographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove interpreted as having been produced by contact with a medium hardness material such as bone, wood or reeds: a) wide flattened surface associated with pits and shallow grooves extending parallel to the main axis of the groove (x20), b) micro-polish developed on protruding phenocrysts indicated by the white arrow exhibiting directionality pattern of abrasion along the main axis of the groove (x500) (similar polish was observed on artefact number 177, see Figure 6b). Traces on the perimeters interpreted as having been produced by contact with a hard stone: c) extremely flat peaks with sharp edges (x20), d) rough bright polish developed on protruding points indicated by the white arrows (x200).

Figure 6: Artefact number 177 showing the concave bottom of the groove and walls extending outward. Locations of microphotographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove interpreted as having been produced by contact with a medium hardness material such as bone, wood or reeds: a) extremely flattened surface at the bottom area of the groove associated with shallow grooves on the sides extending parallel to the axis of the groove and indicating the direction of abrasion (x20), b) translucent thin polish on groundmass associated with patches of thick, bright, smooth polish indicated by the white arrow that developed on phenocrysts exhibiting directionality pattern along the axis of the groove (x100) (similar polish was observed on artefact number 176, see Figure 5b at higher magnification). Traces on the perimeters interpreted as having been produced by contact with a hard stone: c) wide flat peaks associated with small lower surfaces indicating a more intense abrasion (original magnification x6.7), d) rough bright polish developed on protruding points indicated by the white arrows showing no directionality patterns (x200).

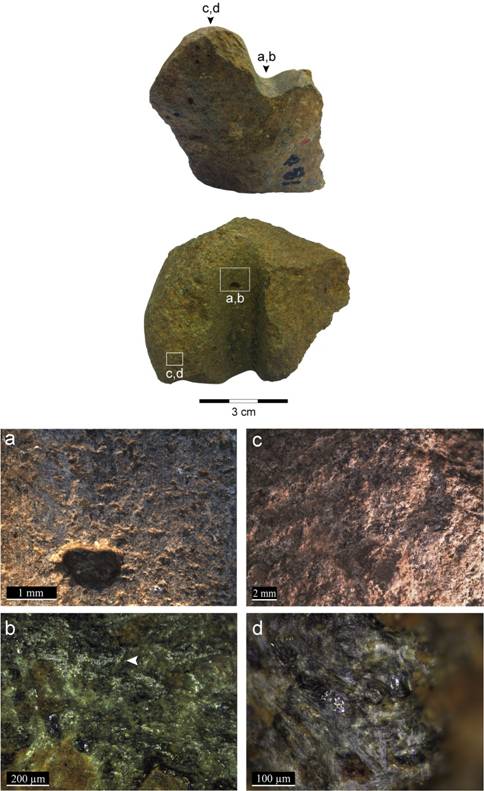

Figure 7: Artefact number 180 is a fragment of a pestle on which a groove was shaped. The groove has a concave bottom with walls extending outward. Locations of microphotographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove are interpreted as having been produced by contact with a medium hardness material such as bone, wood or reeds: a) slight blackening on the bottom of the groove, extremely flat and smooth surfaces associated with lower areas (x6.7), b) translucent, bright and granular polish indicated by the white arrow, exhibiting directionality pattern parallel to the main axis of the groove (x100). Traces on the perimeters interpreted as having been produced by contact with a hard stone: c) levelled rough surface indicating short duration abrasion (x6.7), d) translucent, thin and dull polish extending on a wide surface (x200).

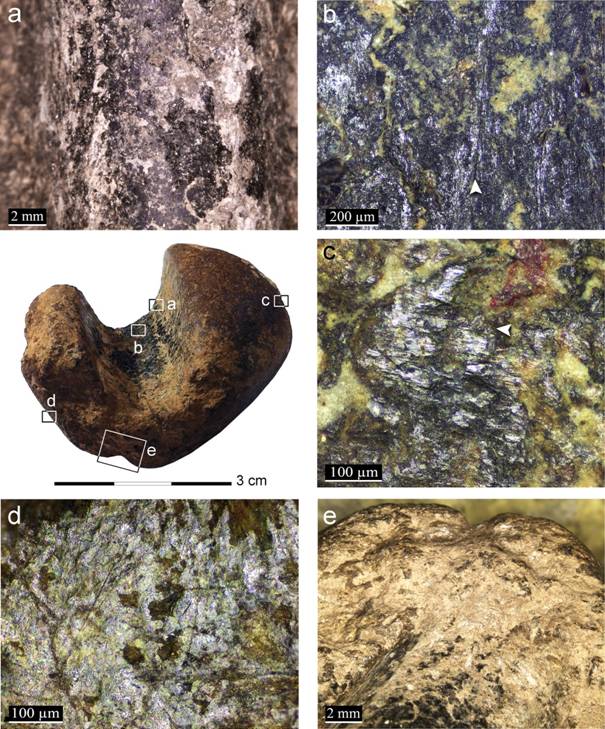

Figure 8: Artefact number 181 showing the concave bottom of the groove and walls extending outward. Locations of microphotographs are indicated by arrows. Traces inside the groove are interpreted as having been produced by contact with a mineral such as sandstone or ochre: a) extreme darkening of the bottom of the groove associated with shallow cracks indicating the application of heat, and flat smooth surface (x6.7), b) thin bright polish with directionality features indicating abrasion along the main axis of the groove, similar to traces observed on experimental basalt abraded against coastal aeolianite ('kurkar') (see Figure 2g) (x100). Traces on the perimeters interpreted as having been produced by contact with hard stone and by crushing minerals: c) bright, thick polish exhibiting directionality features associated with yellow and red coloured powder (probably ochre) interpreted to be produced by crushing action (x200), d) translucent, thin and dull polish extending over a wide area interpreted to be produced by contact with stone and water (x200), e) area exhibiting cracks and crushing interpreted to be produced by the action of crushing minerals (x6.7).

For the six specimens studied, wear on the perimeters was interpreted as the result of contact with a hard stone. Although the artefacts are of different morphology, this observation is consistent, indicating that a specific mechanism caused this type of wear. The most indicative feature is the extremely flat and smooth surface which, under the microscope, appears as extremely flat peaks of the micro-topography (artefacts 171, 172 and 177; Figures 3c, 4c, and 6c respectively). This indicates that the outer face of the implement was abraded against a very hard surface, or against an extremely abrading surface such as sandstone, that truncated the protruding surfaces of the basalt. These flat peaks, associated with unaltered lower surfaces, are observed consistently on a wide area all over the smoothed outer surface. Micro-polish associated with this wear pattern is usually dull, thin and transparent (artefacts 171, 172 and 177; Figures. 3d, 4d and 6d). Although we were not able to replicate this type of polish in our experiments, we assume that water was also used as a lubricant in this type of abrasion, especially because the polish spreads evenly over the entire surface.

A rough and relatively levelled surface is another type of wear observed on the perimeters. This pattern was also interpreted to be produced by contact with a hard stone, but in these cases the abrasion procedure was of shorter duration and probably did not involve a lubricant (water) or an additive (such as sand) and it is possible that pecking was involved prior to the abrasion on stone (artefacts 176, 180 and 181; Figures 5c, 7c, and 8d respectively). Micro-polish usually was not observed (artefact 176; Figure 5d), or it developed only to a low degree (artefact 172; Figure 4d). The polish is local, spreading unevenly on the surface and exhibiting no directionality patterns (artefact 181; Figure 8d). We considered that this pattern might be mistaken for natural surfaces that characterize rolled pebbles, however at this point of research we consider the fact that the wear is homogenous, sometimes associated with polish that shows the direction of the abrasion, to be the most indicative trait for intentional treatment. Additional observations are planned for our future research, focusing on natural surfaces of rolled basalts from different outcrops and textures.

The surfaces inside the groove exhibit flat micro-topography, however with varying degrees of development. Some items exhibit flat protruding peaks with flattening extending slightly into the lower surfaces (artefacts 171 and 172; Figures. 3a and 4a respectively), as well as extremely flat surfaces with fewer low areas, indicating a more intense abrasion for a longer time (artefacts 176, 177, 180 and 181; Figures. 5a, 6a, 7a and 8a respectively). These features indicate contact with medium hardness materials such as wood, bone, reeds (to a lesser degree) or harder such as stone, similar to patterns observed in our experiments (Figure 2e-h).

We identified at least two types of use-wear polish in the grooves not observed on the perimeters. The first is the micro-polish with a domed or reticular distribution (depending on the level of polish development) (artefacts, 172, 176, 177; Figures. 4b, 5b, 6b). This micro-polish is smooth in texture, appearing thick and opaque and exhibiting directionality patterns. The polish seems similar to that produced by contact with reeds (especially for artefacts 171, 172 and 180; Figures. 3b, 4b and 7b). However, the polish developed in patches mainly on phenocrysts. Therefore, at this point, this type of polish was interpreted as having been produced by contact with reeds, wood or bone as they are characterized by similar wear patterns (that can be clearly distinguished only on wider polished surfaces). Additional experiments and observations are planned for future research to assist in arriving at a more specific interpretation.

The second type of polish is totally different, exhibiting flat polished surface that is heavily striated on the groundmass. Observed only on artefact number 181 (Figure 8), it represents a unique function, different from the other artefacts. The traces inside the groove are similar to those produced in our experiments by contact with stone (such as ‘kurkar’) (Figure 2g), therefore we associate this type of polish to stone working. The blackening of the groove bottom, associated with shallow cracks is outstanding, indicating alteration due to the application of heat (Figure 8a). Observations on the black surface and cracks showed no traces of residue as was previously suggested (Wilke & Quintero 2009). Striations clearly indicate a back and forth abrasion along the main axis of the groove (Figure 8b). Additional evidence to support the use of this artefact with stone working are the remains of yellow and red coloured powder inside pits on the perimeter’s surface outside the groove (Figure 8c). This powder, which is probably the remains of ochre, is associated with a heavily striated, thicker and brighter polish indicating another action using the perimeters, probably for crushing the mineral. Clear crushing traces are evident on one of the edges supporting this reconstruction, so it can be assumed that this tool was used to abrade stone using the groove to create a cylindrical object, and to crush stone (ochre) to create a powder (Figure 8e).

The analysis of the grooved basalts produced information that can be used to reconstruct several aspects relating to the production and utilization of these unique artefacts from Natufian el-Wad Terrace. The most straightforward result in the analysis is that traces observed on the surfaces outside the groove (the perimeters) are different from those observed inside the groove. We attribute the traces outside the groove to the shaping of the basaltic instrument and the traces observed inside the groove to the specific use of this instrument, which is the abrasion of various materials in order to create smoothed, rounded or cylindrical shapes.

A persistent question is whether the grooves were shaped during the manufacturing process or rather formed as a result of a continuous abrasion of a round narrow object against the basalt. Based on our experiments we conclude that abrading the basalt fragment against a hard stone such as flint or basalt is essential in order to substantially modify the shape of the basalt. Abrading bone, wood or reeds on compact basalt is ineffective as these materials are not abrasive enough, and they are too soft, elastic and sticky. Hence, the groove is a part of the instrument, shaped before its use in order to work the abraded materials.

For the Natufian grooved basalt items, the micro-topography of the inside surface of the grooves is totally or relatively flat. This indicates that it was shaped by abrasion against a hard stone such as flint or a softer but more abrasive stone such as sandstone. It is possible that the shaping of the groove was initiated by cutting with a flint knife, as shallow grooves were occasionally observed inside the groove, but massive reduction of the groundmass must have been done using a hard stone. Micro-polish observed under high magnification (x500), interpreted to be the result of contact with softer materials such as wood, bone or reeds, indicate a secondary abrasion following the shaping of the groove by contact with a hard material.

As for the function of the grooved instruments, the first indication that the grooves were shaped for specific functions is the fact that the micro-wear observed on the inside of the grooves is different from the micro-wear observed on the perimeter. Based on our experiments and results of the use-wear analysis we conclude that objects made of stone or mineral, bone, wood or reeds were abraded in a back and forth motion along the axis of the groove.

It seems evident that the role of the groove was to stabilize and control the movement along the axis of the groove. But considering that the groove was shaped first, and considering that micro-wear on the bottom and side walls of the groove is similar, we posit that the aim was to abrade an object into a cylindrical-like shape. The grooved basalts might have also been used as straighteners of shafts made of reeds, wood or bone with the application of heat, occasionally indicated by the cracks and blackened surfaces inside the groove. In that case, the basalt serves as a heat reservoir as well as an abrader. Given their size, the grooved basalts were used as mobile instruments to shape artefacts that did not exceed 2 cm in diameter. These might have been arrow shafts, handles or awls, but also artefacts such as crayons and beads made of minerals and, in the case of artefact #181, ochre.

Our data allow us to reconstruct the “life history” of the grooved basalts, as follows:

Stage 1: Collecting fragments from basaltic outcrops: the grooved basalts found at el-Wad Terrace were shaped on compact basalts probably from sources in the Jezreel Valley or beyond (e.g., Galilee, Golan Heights, Jordan Valley). The original shape of the collected basalts on which these instruments were shaped is unknown as it was totally modified into a pre-planned shape; however we can assume that the basalts were relatively small pebbles and in some cases fragments. As noted above, reused tools, specifically basalt pestles were also used as blanks for the production of grooved items.

Stage 2: Abrasion of the perimeter: at an initial stage, whether aimed to be used as pestles or as grooved artefacts, the blanks were abraded against a hard surface (stone) perhaps using a lubricant (such as water) to enhance the polishing. The abrading surface was probably a relatively wide surface that enabled a free movement of the basalt against it.

Stage 3a: Primary use as a pestle: some of the tools (Figures. 3 and 7) were probably used for crushing or pounding. This stage is reconstructed based only on the morphological characteristics of some of the grooved basalts. We found no use-wear related to this function.

Stage 3b: Shaping the groove on the smoothed basalt: it is possible that the initiation of the groove was done by cutting with a (flint) knife and then against a hard but narrow surface to widen the groove. Once the groove was deep and wide enough to hold the shaft or other worked materials, it was ready to be used.

Stage 4: Abrading or straightening elongated rounded objects made of mineral, wood, bone or reeds: these tasks might have involved sitting around a fire for heating and re-heating the grooved basalt item. The shape and size of the grooved basalt items indicate that these instruments were probably held by hand during use, but it is also possible that they were placed on the ground and stabilized on a surface, especially if heating was involved. In some occasions the basaltic instruments were used for a secondary task, such as crushing minerals such as ochre (as it was observed for artefact #181) using the perimeter.

Stage 5: Discard: after using the grooved basalt for an unknown period, these tools were discarded. All the grooved basalts are broken, so intentional breaking, as occasionally suggested for ground stone tools, might have occurred (for a review, see Adams 2008). Worth mentioning is that traces are cut by the break, which is a clear indication for the breakage following the use. The items were embedded in EN living quarters along with great quantities of other tool-making debris as well as food refuse, at least some of which are in primary depositional context (Yeshurun et al. 2013; 2014a). This possibly indicates that the place of use of most of the grooved items was just outside of the Structure II dwelling (Figure 1c), within the Wall I architectural complex. Ground stone items and particularly the grooved basalts are either rare or absent outside of the Wall I complex (Rosenberg et al. 2012), further pointing to their domestic context of use.

Summing up, the preliminary results of the use-wear analyses of the six items discussed above yielded information concerning the production and utilization of the grooved basalts found on the EN living floors of el-Wad Terrace. More data are required, especially for more precise interpretation of the use-wear polish and in distinguishing the production procedure with experiments on already smoothed basalts or with naturally rolled pebbles. Nonetheless, our results suggest that Natufian grooved implements might have been used as shaft-straighteners as previously argued. However they might also have been employed as abraders as microscopic traces indicate contact with various materials such as reeds, bone, wood or minerals. The evidence provided by the use-wear analysis supports an assessment by which the Natufians invested much energy in shaping these instruments. The reconstruction of their use indicates the deep knowledge of the mechanical properties of materials as they were aware of the advantages of using basalt, especially with the addition of the application of heat. This unique tool demonstrates another aspect of the nature of the Natufian culture, advancing towards sedentary complex communities in the Levant.

The renewed excavations and laboratory work at el-Wad Terrace are supported by the Israel Science Foundation (grant 913/01), the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the Irene Levi-Sala Care Archaeological Foundation and the Faculty of Humanities, University of Haifa and the Carmel Drainage Authority. El-Wad is located in the Nahal Me‘arot Nature Reserve managed by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. The material published here corresponds to IAA permits G-5/1999, G-25/2000, G-15/2001, G-8/2002, G-13/2003, G-28/2004, G-13/2005, G-20/2006, G-3/2007, G-2/2008, G-4/2009, G-5/2010, G-6/2012, G-4/2015. We wish to thank the reviewers for their helpful comments and A. Regev for the graphics.

Adams, J.L. 2002, Ground Stone Analysis. The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, 320 p.

Adams, J.L. 2008, Beyond the broken. In: New Approaches to Old Stones, (Rowan, Y. and Ebeling, J., Eds.), Equinox Publishing Ltd, London: p. 213-229.

Adams, J.L., Delgado, S., Dubreuil, L., Hamon, C., Plisson, H., & Risch, R. 2009, Functional analysis of macro-lithic artefacts: a focus on working surfaces. In: Non-Flint Raw Material Use in Prehistory: Old Prejudices and New Directions, (Sternke, F., Eigeland, L. & Costa, L.J., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1939, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 43-66.

Bar-Yosef, O. 1983, The Natufian in the southern Levant. In: The Hilly Flanks and Beyond, (Young Jr., T.C., Smith, P.E.L. and Mortensen, P., Eds.), Oriental Institute, Chicago: p. 1-42.

Bar‐Yosef, O. 1998. The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 6(5): 159-177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::AID-EVAN4>3.0.CO;2-7

de Beaune, S.A. 1993, Nonflint tools of the Early Upper Paleolithic. In: Before Lascaux: The Complex Record of the Early Upper Paleolithic, (Knecht, H., Pike-Tay, A. & White, E., Eds.), Crc Press, Ann Arbor: p. 163-191.

Belfer-Cohen, A. 1988, The Natufian Settlement at Hayonim Cave – A Hunter-Gatherer Band on the Threshold of Agriculture. Unpublished Ph. D. Dissertation, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem. 603 p.

Belfer-Cohen, A. 1991, The Natufian in the Levant. Annual Review of Anthropology, 20: 167-186. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.001123

Belfer-Cohen, A., & Bar-Yosef, O. 1981, The Aurignacian at Hayonim Cave. Paléorient, 7(2): 19-42. doi:10.3406/paleo.1981.4296

Belfer-Cohen, A., & Bar-Yosef, O. 2002, Early sedentism in the Near East. A bumpy ride to village life. In: Life in Neolithic Farming Communities. Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation (Kuijt, I. Ed.), Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York: p. 19-38. doi:10.1007/b110503

Cauvin, J. 2000, The Birth of the Gods and the Origins of Agriculture. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 288 p.

Dubreuil, L. 2002, Etude fonctionnelle des outils de broyage natoufiens: Nouvelles perspectives sur l’émergence de l’agriculture au Proche-Orient. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Bordeaux I, Bordeaux, 469 p.

Dubreuil, L. 2004, Long-term trends in Natufian subsistence: A use-wear analysis of ground stone tools. Journal of Archaeological Science, 31(11): 1613-1629. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.04.003

Dubreuil, L. 2008, Mortar versus grinding-slabs and the neolithization process in the Near East. In: “Prehistoric Technology” 40 Years Later: Functional Studies and the Russian Legacy, (Longo, L. & Skakun, N., Eds.), Museo Civico di Verona, and Universita degli Studi di Verona, Verona: p. 169-177.

Dubreuil, L., & Grosman, L. 2009, Ochre and hide-working at a Natufian burial place. Antiquity, 83(322): 935-954. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00099269

Dubreuil, L., & Grosman, L. 2013, The life history of macrolithic tools at Hilazon Tachtit Cave. In: Natufian Foragers in the Levant: Terminal Pleistocene Social Changes in Western Asia, (Bar-Yosef O. & Valla F.R., Eds.), International Monographs in Prehistory, Ann Arbor: p. 527-543.

Dubreuil, L., & Savage, D. 2013, Ground stones: a synthesis of the use-wear approach. Journal of Archaeological Science, 48: 139-153. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.023

Eckmeier, E., Yeshurun, R., Weinstein-Evron, M., Mintz, E., & Boaretto, E. 2012, 14C dating of the Early Natufian at el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel: methodology and materials characterization. Radiocarbon, 54(3-4): 823-836. doi:10.2458/azu_js_rc.v54i3–4.16166

Edwards, P.C. 2013, Limestone artefacts. In: Wadi Hammeh 27: An Early Natufian Settlement at Pella in Jordan, (Edwards, P.C., Ed.), Brill, Leiden: p. 235-247.

Edwards, P.C., & Webb, J. 2013, The basaltic artefacts and their origin. In: Wadi Hammeh 27: An Early Natufian settlement at Pella in Jordan, (Edwards, P.C., Ed.), Brill, Leiden: p. 205-233.

Eitam, D. 2008, Plant food in the Late Natufian: the oblong conical mortar as a case study. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 38: 133-151. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23386442

Garrod, D.A.E. 1957, The Natufian culture: the life and economy of a Mesolithic people in the Near East. Proceedings of the British Academy, 43: 211-227.

Garrod, D.A.E., & Bate, D.M.A. 1937, The Stone Age of Mount Carmel. Vol. I. Excavations at the Wadi Mughara. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 240 p.

Gopher, A., & Orrelle, E. 1996, An alternative interpretation for the material imagery of the Yarmoukian, a Neolithic culture of the sixth millennium BC in the southern Levant. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 6(2): 255-279. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001736

Hardy-Smith, T., & Edwards, P.C. 2004, The garbage crisis in prehistory: Artefact discard patterns at the Early Natufian site of Wadi Hammeh 27 and the origins of household refuse disposal strategies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 23(3): 253-289. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2004.05.001

Hayden, B., Canuel, N., & Shanse, J. 2013, What was brewing in the Natufian? An archaeological assessment of brewing technology in the Epipaleolithic. Journal of Archaeological Method Theory, 20(1): 102-150. doi:10.1007/s10816-011-9127-y

Hermansen, B.D. 1997, Patterns of symbolism in the Neolithic, seen from Basta. Neo-Lithics, 2(97): 6.

Hole, F., Flannery, K.V., & Neely, J.A. 1969, Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain, an Early Village Sequence from Khuzistan, Iran. Memoirs of the Museum of Anthropology 1, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 440 p.

Kaufman, D., Yeshurun, R., & Weinstein-Evron, M. 2015, The Natufian sequence of el-Wad Terrace: Seriating the lunates. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society 45: 143-157

Nadel, D., Filin, S., Rosenberg, D., & Miller, V. 2015, Prehistoric bedrock features: recent advances in 3D characterization and geometrical analyses. Journal of Archaeological Science, 53: 331-344. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.10.029

Nadel, D., & Lengyel, G. 2009, Human-made bedrock holes (mortars and cupmarks) as a Late Natufian social phenomenon. Archaeology, Ethnology and Anthropology of Euroasia, 37(2): 37-48. doi:10.1016/j.aeae.2009.08.012

Nadel, D., & Rosenberg, D. 2010, New insights into Late Natufian bedrock features (mortars and cupmarks). Eurasian Prehistory, 7(1): 65-87.

Perrot, J. 1966, Le gisement Natufian de Mallaha (Eynan), Israël. L’Anthropologie, 70(5-6): 437-484.

Rosenberg, D. 2011, התפתחות, המשכיות ושינוי: תעשיות האבן בתרבויות הקרמיות המוקדמות בדרום הלבאנט. Ph.D. thesis, University of Haifa, Haifa, 572 p. (in Hebrew) (“Development, continuity and change: the stone industries of the early ceramic-bearing cultures of the Southern Levant”)

Rosenberg, D. 2013, Not ‘just another brick in the wall?’ The symbolism of groundstone tools in Natufian and Early Neolithic Levantine constructions. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 23(2): 185-201. doi:10.1017/S095977431300022X

Rosenberg, D., Kaufman, D., Yeshurun, R., & Weinstein-Evron, M. 2012, The broken record: The Natufian groundstone assemblage from el-Wad Terrace (Mount Carmel, Israel) – Attributes and their interpretation. Journal of Eurasian Prehistory, 9(1-2): 93-128.

Rosenberg, D., & Nadel, D. 2011, On floor level: PPNA indoor cupmarks and their Natufian forerunners. In: The State of the Stone: Terminologies, Continuities and Contexts in Near Eastern Lithics. Proceedings of the 6th PPN Conference on Chipped and Ground Stone Artefacts in the Near East, Manchester, 3rd-5th March 2008, (Healy, E., Maeda, O., & Campbell, S., Eds.), Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence, and Environment Vol. 13, Ex Oriente, Berlin: p. 99-108.

Rosenberg, D., & Nadel, D. 2014, The sounds of pounding: Boulder mortars and their significance to Natufian burial customs. Current Anthropology, 55(6): 784-812. doi:10.1086/679287

Samzun, A. 1994, Le mobilier en pierre. In: Le Gisement de Hatoula en Judée Occidentale, Israël, Mémoires et Travaux du Centre de Recherche Français de Jérusalem 8, (Lechevallier, M., & Ronen, A., Eds.), Association Paléorient, Paris: p. 193-226 (in French) (The ground-stone tool assemblage)

Savage, D. 2014, Arrows Before Agriculture? A Functional Study of Natufian and Neolithic Grooved Stones. Unpublished MA Thesis no. AAC1564003, Trent University, Peterborough, Canada, 327 p.

Solecki, R.L., & Solecki, R.S. 1970, Grooved stones from Zawi Chemi Shanidar, a Protoneolithic site in northern Iraq. American Anthropologist, 72(4): 831-841. doi:10.1525/aa.1970.72.4.02a00080

Stekelis, M. 1972. The Yarmukian Culture of the Neolithic Period. Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 124 p.

Valla, F.R. 1995, The first settled societies - Natufian (12,500-10,200 BP). In: The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land, (Levy, T.E., Ed.), Leicester University Press, London: p. 170-187.

Valla, F.R. 2009, Une énigme Natoufienne: Les mortiers enterrés. In: De Méditerranée et D'Ailleurs. Mélanges Offerts à Jean Guilaine, (Fabre, D., Ed.). Archives d'Écologie Préhistorique, Toulouse: p. 752-760. (in French) (A Natufian enigma: the buried mortars)

Valla, F.R. 2012, Le matériel en pierre. In: Les Fouilles de la Terrasse d’Hayonim (Israël) 1980-1981 et 1985-1989, (Valla, F.R., Ed.). Mémoires et Travaux du Centre de Recherche Français à Jerusalem Vol. 10, De Boccard, Paris: p. 299-320. (in French) (The ground-stone tool assemblage)

Valla, F.R., Bar-Yosef, O., Smith, P., Tchernov, E., & Desse, J. 1986, Un nouveau sondage sur la terrasse d'El Ouad, Israel. Paléorient, 12(1): 21-38. (in French) (A new survey at el-Wad Terrace, Israel) doi:10.3406/paleo.1986.4395

Vered, A. 2013, Grooved stones in the southern Levant: Typology, function and chronology. In: Stone Tools in Transition: From Hunter-Gatherers to Farming Societies in the Near East, (Borrell, F., Ibáñez, J.J., & Molist, M., Eds.), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona: p. 435-447.

Voigt, M.M. 1983, Hajji Firuz Tepe, Iran: The Neolithic Settlement. University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania, 528 p.

Weinstein-Evron, M. 1998, Early Natufian el-Wad Revisited. Études et Recherches Archéologiques de l’Université de Liège, ERAUL Vol. 77, Service de Préhistoire, Université de Liège, Liège, 255 p.

Weinstein-Evron, M. 2009, Archaeology in the Archives: Unveiling the Natufian Culture of Mount Carmel. ASPR Monograph Series Vol. 7, Brill, Boston, 148 p.

Weinstein-Evron, M., .Lang, B., & Ilani, S. 1999, Natufian trade/exchange in basalt implements: Evidence from northern Israel. Archaeometry, 41(2): 267-273. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1999.tb00982.x

Weinstein-Evron, M., Lang, B., Ilani, S., Steinitz, G., & Kaufman, D. 1995, K/AR dating as a means of sourcing Levantine Epi-Paleolithic basalt implements. Archaeometry, 37(1): 37-40. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1995.tb00725.x

Weinstein-Evron, M., Kaufman, D., Bachrach, N., Bar-Oz, G., Bar-Yosef Mayer, D.E., Chaim, S., Druck, D., Groman-Yaroslavski, I., Hershkovitz, I., Liber, N., Rosenberg, D., Tsatskin, A., & Weissbrod, L. 2007, After 70 years: new excavations at the el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 37: 37-134.

Weinstein-Evron, M., Kaufman, D., & Bird-David, N. 2001, Rolling stones: basalt implements as evidence for trade/exchange in the Levantine Epi-Palaeolithic. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society, 31: 25-42. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23380245

Weinstein-Evron, M., Kaufman, D. & Yeshurun, R. 2013, Spatial organization of Natufian el-Wad through time: combining the results of past and present excavations. In: Natufian Foragers in the Levant: Terminal Pleistocene Social Changes in Western Asia, (Bar-Yosef, O., & Valla, F.R., Eds.), International Monographs in Prehistory, Ann Arbor: p. 88-106.

Weinstein-Evron, M., Yeshurun, R., Kaufman, D., Boaretto, E., & Eckmeier, E. 2012, New radiocarbon dates for the Early Natufian of el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel, Israel. Radiocarbon, 54(3-4): 813-822. doi:10.3406/paleo.1991.4542

Weissbrod, L., Bar-Oz, G., Yeshurun, R., & Weinstein-Evron,M. 2012, Beyond fast and slow: The mole rat Spalax ehrenbergi (Order Rodentia) as a test case for subsistence intensification of complex Natufian foragers in southwest Asia. Quaternary International, 264: 4-16. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.05.021

Wilke, P.J., & Quintero, L.A. 2009, Getting it straight: shaft-straighteners in a grooved-stone world. In: Modesty and Patience: Archaeological Studies and Memories in Honour of Nabil Qadi “Abu Salim”, (Qadi, N., Gebel, H.G., Abdel-Kafi, Z., Kafafi, O. Al-Ghul, & Yarmūk, J., Eds.), Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan: p. 1-5.

Wright, K.I. 1991, The origins and the development of ground-stone assemblages in Late Pleistocene southwest Asia. Paléorient, 17(1): 19-45. doi:10.3406/paleo.1991.4537

Wright, K.I. 1994, Ground-stone tools and hunter-gatherer subsistence in southwest Asia: Implication for the transition to farming. American Antiquity, 59(2): 238-263. doi:10.2307/281929

Wright, K.I., Critchley, P., & Garrard, A. 2008, Stone bead technologies and early craft specialization: Insights from two Neolithic sites in eastern Jordan. Levant, 40(2): 131-165. doi:10.1179/175638008X348016

Yeshurun, R., Bar-Oz, G., Kaufman, D., & Weinstein-Evron, M. 2013, Domestic refuse maintenance in the Natufian: Faunal evidence from el-Wad Terrace, Mount Carmel. In: Natufian Foragers in the Levant: Terminal Pleistocene Social Changes in Western Asia, (Bar-Yosef, O., & Valla, F.R., Eds.), International Monographs in Prehistory. Archaeological Series Vol. 19, Ann Arbor: p. 118-138.

Yeshurun, R., Bar-Oz, G., Kaufman, D., & Weinstein-Evron, M. 2014a, Purpose, permanence and perception of 14,000-year-old architecture: Contextual taphonomy of food refuse. Current Anthropology, 55: 591-618. doi:10.1086/678275

Yeshurun, R., Bar-Oz, G., & Weinstein-Evron, M. 2014b, Intensification and sedentism in the Terminal Pleistocene Natufian sequence of el-Wad Terrace (Israel). Journal of Human Evolution, 70: 16-35. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2014.02.011