Raw material sourcing in the Middle Paleolithic site of Gruta da Oliveira (Central Limestone Massif, Estremadura, Portugal)

UNIARQ, Centro de Arqueologia Universidade de Lisboa, School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon. Alameda da Universidade, 1600-214 Lisboa, Portugal. Email: hamatias@gmail.com

The cave site of Gruta da Oliveira is located in the Almonda karst system, at the interface between the Central Limestone Massif of Portuguese Estremadura (CLM) and the adjacent Sedimentary Basin of the River Tagus (TSB). The cave presents a stratification dated to ~37-107 ka containing hearth features, Neanderthal skeletal remains, as well as fauna, microfauna and wood charcoal remains. The lithic assemblages are large and feature a diverse range of raw materials.

Knappable lithic raw materials in primary, sub-primary and secondary position in the CLM and the TSB were systematically surveyed and sampled. The characterization of the geological samples was carried out at both the macro- and the microscopic scales and data were systematized under the petroarcheological and “evolutionary chain of silica” approaches.

The study of the lithic assemblage from layer 14 (dated to the ~61-93 ka 95.4% probability interval by TL) indicates that the Gruta da Oliveira Neanderthals used quartzite, quartz and flint from sources located less than 30 km away in both the CLM and the TSB.

Keywords: Almonda karst system; Gruta da Oliveira; Middle Paleolithic; Neanderthals; petroarcheology; flint

The Almonda karst system, an extensive network of cavities associated with the spring of the River Almonda, is located in the Meso-Cenozoic Western Border (MCWB) of Iberia, at the boundary between the Central Limestone Massif (CLM) and the Tagus Sedimentary Basin (TSB). Among those of archeological interest, the lowermost passages, 5-15 m above the current spring, contain deposits of Upper Paleolithic and later prehistoric age (Almeida et al. 2004; Angelucci & Zilhão 2009; Zilhão 1997) (Figure 1). Higher up in a 70 m escarpment, the labyrinth of passages features several collapsed cave entrances, two of which have been cleared for archeological excavation, ongoing since 1991.

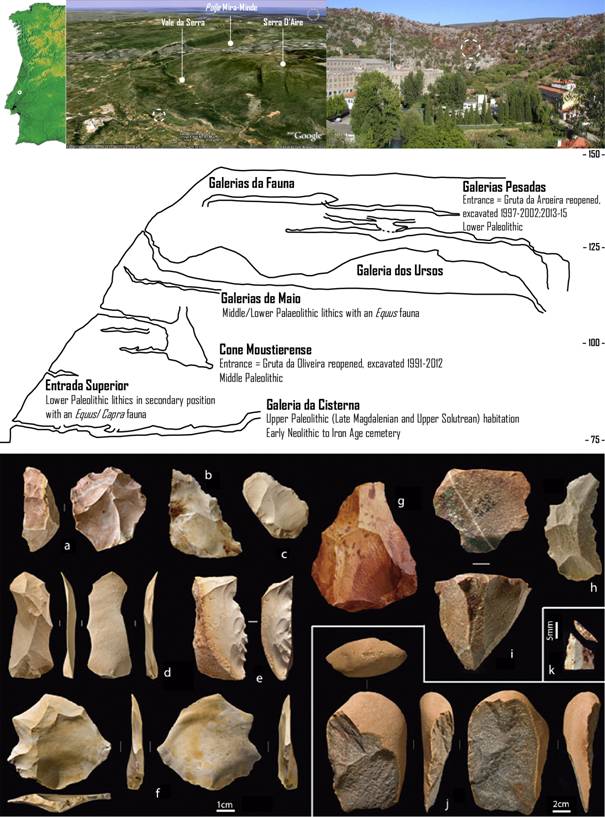

Figure 1. The location of Gruta da Oliveira (top), schematic cross-section of the Almonda escarpment showing the position of the main archeological sites (center), and a selection of stone tools from Gruta da Oliveira (base): a. Levallois core, layer 20; b. Denticulate sidescraper, layer 26; c. Sidescraper, layer 26; d. Levallois blade, layer 20; e. Denticulate, layer 14; f. Levallois flake, layer 19; g. Levallois core, layer 13; h. Denticulate, layer 26; i. Pyramidal core, layer 10; j. hachereau, layer 20; k. Truncated bladelet, layer 14; a.-f. and k., flint; g. -j., quartzite. (Photos b. to k. by João Zilhão; Photos a., j. and k. by José Paulo Ruas (after Hoffmann et al. 2013; Zilhão et al. 2013)). [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

At the top of the escarpment, the Gruta da Aroeira, excavated between 1997 and 2002 and anew since 2013, features an Acheulian breccia dated to >420 ka that yielded an industry with handaxes and other bifacial items (Hoffmann et al. 2013; Marks et al. 2002). Lower down, the Middle Paleolithic site of Gruta da Oliveira preserved a ~13 m-thick sequence of stratified Mousterian occupations dated by U-series, Thermoluminescence and Radiocarbon to between ~37,000 and ~107,000 years ago (Angelucci & Zilhão 2009; Hoffmann et al. 2013; Richter et al. 2014). Neanderthal osteological remains were found in several levels of the Oliveira sequence, which also yielded lithic and faunal remains allowing the identification of activity areas (knapping and food processing) organized around fireplaces; the lithic assemblages feature Levallois and Kombewa reduction methods alongside the production of elongated, Upper Paleolithic-type blanks (Figure 1 - i. and k.) (Marks et al. 2001; Zilhão et al. 2013).

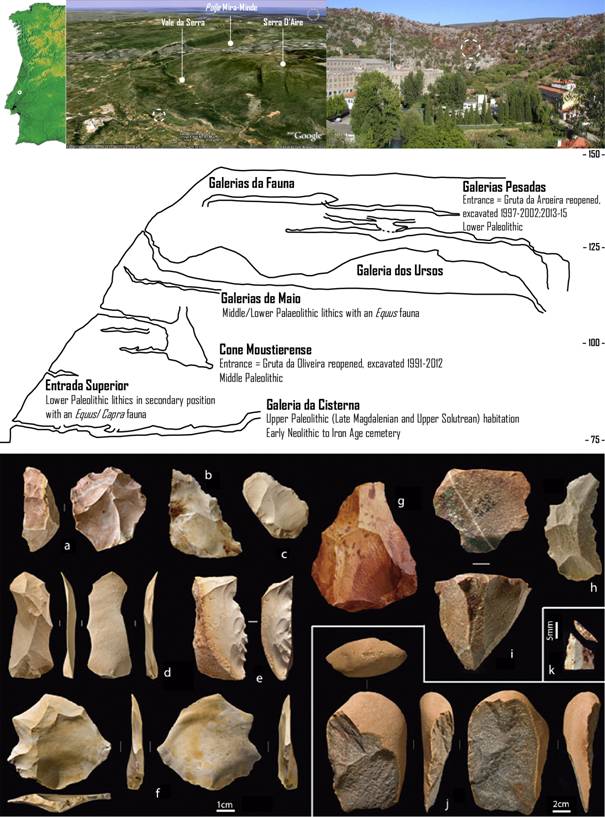

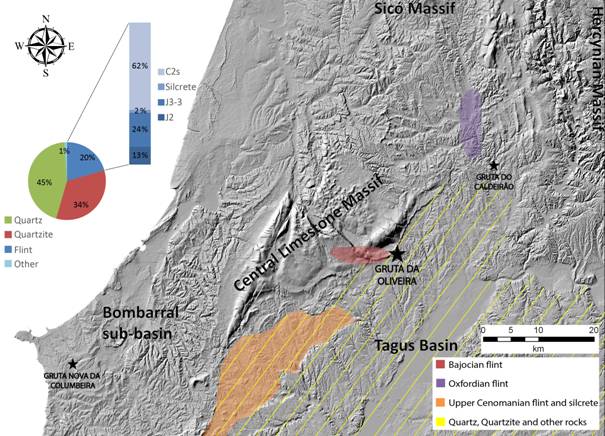

The main goal of this study was to determine the lithic raw material sources exploited in order to reconstruct the regional Neanderthals’ territoriality and subsistence strategies. For this purpose, a reference collection of raw material sources (Figure 2) was compared with a sample of stone tools from layer 14 (dated to the ~61-93 ka 95.4% probability interval by TL), used as a case study.

Interest in lithic raw material sources is documented since the 19th century, but it was not until the 1970’s and 1980’s that Petroarcheology became established as an autonomous discipline with a well-defined methodological frame (Mangado Llach 2002). Annie Masson (1979; 1981) proposed a methodology for macro- and microscopic analyses of silicifications, while Jean-Michel Geneste (1985) correlated sourcing data with lithic technology for the Mousterian of southwestern France, introducing a spatial dimension in lithic technology studies (Geneste 1991).

In Portugal, mobility and raw material procurement where first addressed in early 1990s, in the context of a study of the Upper Paleolithic of the Rio Maior basin. This preliminary work used macroscopic data and only considered the Upper Cenomanian flints occurring in the siliciclastic formations of the TSB, where archeological sites are located less than 5 km from such flint sources (Marks et al. 1991). Recent petroarcheological studies have also included geochemical analyses (Pereira et al. 2016; Shokler 2002).

Systematic surveys aiming at the identification of raw material sources were carried out in the Côa Valley in the mid-1990’s, in the wake of the discovery of its Paleolithic rock art and coeval settlement sites (Aubry 2005; Aubry et al. 2012; Aubry & Mangado Llach 2003a; b; 2006; Aubry et al. 2004; Mangado Llach 2002). Despite their absence in the Hercynian Massif region and therefore in the Côa, flint and silcrete are systematically present in the valley’s Upper Paleolithic assemblages, and could be sourced to geological formations located more than 150 km to East and Southwest, including the CLM and TSB regions (2003a; b). Using a GIS least-cost algorithm, models of the circulation of these resources and the size of exploitation territories were proposed as proxies for the social networks that knitted together the Upper Paleolithic groups living in the different geographical areas concerned (Aubry et al. 2016; Aubry et al. 2012).

Subsequent studies in southern Portugal include Veríssimo’s (2004; 2005) survey and macroscopic characterization of Jurassic flint in primary and secondary position in the region of Vila do Bispo, Burke’s (Bisson et al. 2011; Burke et al. 2011) survey and geochemical analysis of jasper sources in the context of a study of the Middle Paleolithic in western Alentejo, and Gaspar’s (2009; Gaspar et al. 2009) research on the igneous and metamorphic rocks used in the Neolithic site of Laginha 8. In the MCWB, Jordão (2010) determined the origin of local and regional flints used in the Chalcolithic assemblage of São Mamede, while Gameiro (2003; 2012; Gameiro et al. 2008) undertook a petrographic characterization of Magdalenian assemblages in the Sicó massif and the Rio Maior basin, as well as in Lapa dos Coelhos, a site in the Almonda karst system. In the latter, preliminary results concerning the Gruta da Oliveira material were reported by Aubry et al. (2014) and Matias (2012).

Figure 2. Detail of the Geological Map of Portugal (1:500.000, resized) (Delfim de Carvalho et al. 1992), showing the Central Limestone Massif and surrounding area of the Tagus Sedimentary Basin, with location of the geological samples used in this study. [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

Considering the concept of chaîne opératoire in its application to knapping (Leroi-Gourhan 1964), the acquisition of raw materials is logically the first stage of the reduction sequence (Geneste 1991). Thus, the study of the origin and proportions of the different types of raw materials present in an archeological stone tool assemblage should be the first step in its study (Almeida et al. 2003; Tixier et al. 1980).

Here, available (even though, concerning existent silicifications, their resolution is low), bibliographic and cartographic data were used to define locations in the TSB and CLM to be targeted for survey and sample collection. Samples were analyzed macroscopically using a stereomicroscope (OLYMPUS SZ61 up to x45 with a coupled photographic camera OLYMPUS SC20), and thin sections were observed under the microscope (CARL ZEISS Axiophot Pol up to x200 with coupled photographic camera Sony DXF-S500).

Flint and other silicifications (e.g., silcrete) were typed according to geological origin, paleoenvironment of formation (Bressy 2003; Séronie-Vivien & Séronie-Vivien 1987) and the “evolutionary chain of silica” concept proposed by Fernandes & Raynal (2006; Fernandes et al. 2008), adapted by Aubry et al. (2012). Sedimentary rocks, like flint, preserve features resulting from complex physico-chemical and mechanical processes related to their deposition environment, making it possible to classify them according to specific genetic and stratigraphic position, paleogeographic environment and aspects of their post-genetic history relating to the present location of the source (Fernandes & Raynal 2006).

Macroscopical analysis under the binocular stereoscope considered color and its distribution, transparency, grain size, texture (after Dunham 1962), sedimentary structures, skeletal and other bioclastic elements, porosity and non-skeletal elements, surface condition, weathering, cortex type, degree of cortex rounding, and knapping quality. Thin sections observed under the microscope focused on mineralogy and crystallization; the siliceous components, their crystal type and size, as well as their diagenetic and post-diagenetic phases of silicification were described alongside the non-siliceous and detrital components. These data are summarized in Table 1.

The same approach, bar microscopic analysis, which could not be carried out in this initial stage of the Gruta da Oliveira research, was applied to the archeological material. Layer 14 was selected due to its high level of stratigraphic integrity, attested by the presence of a fireplace and associated lithic and bone scatters (Angelucci & Zilhão 2009; Nabais 2011; Zilhão et al. 2010; Zilhão et al. 2013). The analyzed sample comprises 3071 lithic artifacts (out of the layer’s total of ~7700) retrieved within an area of 6m2 (grid units L21, M19, M20, N19, O19, P16 and P19) (Table 2). The Levallois, Kombewa and discoidal methods are represented among both flint and quartzite. The most frequent tools are notches, followed by denticulates, retouched flakes and blades, and sidescrapers.

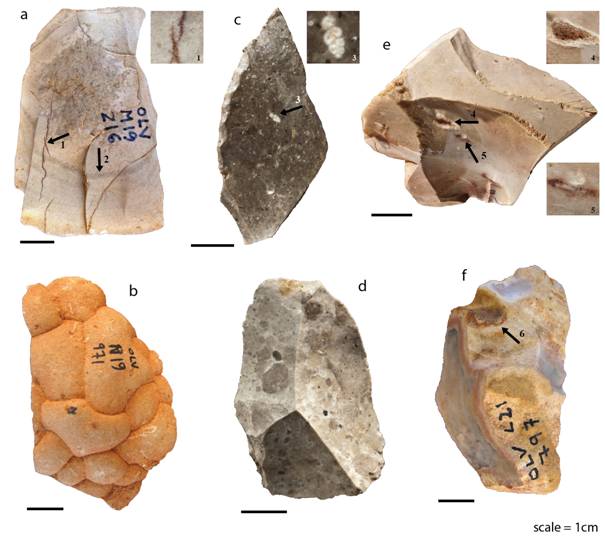

The flint from the cave presents a significant level of weathering. Desiliconization (Bressy 2003) or flint necrosis (Vignard & Vacher 1964) is present. When broken, flints with this type of weathering show a whitish powder core with no structure or consistency and a hard, external, ~1 mm-thick shell preserving some diagnostic elements (texture, structure fossils, etc.) but lacking others (color and translucency). This “necrosis” has been related to the dissolution and neogenesis of silicon in alkaline environments with water circulation, characteristic of cave sites (Masson 1981). Different degrees of weathering are often observed across different areas of the site, within the same stratigraphic unit, and such differences are therefore devoid of chronological meaning (Rottlander 1975).

Despite these weathering problems, the lithic assemblage from layer 14 preserved enough of the structure, texture and other recognizable and distinctive features of the raw materials. Comparison with the geological samples and, hence, identification of the flint sources used, was therefore possible.

Table 1. Silicification types from CLM and TSB. (a) Types are named after geologic map codes followed by a sequential number. (b) 0 (In situ outcrops), 1 (sub-primary outcrops), 2 (colluvial occurrence), 3 (recent river deposits), 4 (old alluvial deposits). (c) BRE (brechoidal), LAM (lamination), LCR (liesegang concentric rings), MLR (multiple liesegang rings), PER (peloidal relict). (d) CNG (conglomerate), GRN (grainstone), MUD (mudstone), PAC (packstone), SAN (sandstone), WAC (wackstone). (e) CAL (undetermined chalcedony), CAL-LF (chalcedony length-fast), CAL-LS (chalcedony length-slow), CQ (criptoquartz), mQ-CQ (microquartz-cryptoquartz), DOL (dolomite), MQ (macroquartz), mQ (microquarzt), Q (alpha-quartz). (f) BIV (bivalve), CHA-O (Charophyta gyrogonite), CHA-S (Charophyta stem), ESP-M (monoaxone spicule), ESP-T (triaxone spicule), FRAG-IND (Undetermined fragment). FOR (foraminifer), GAS (gastropod), INS (insertae sedis), OST (ostracod). (g) CaCO3 (calcite), FEN (fenestral porosity), INT (intraclast), MO (organic material), MOL (moldic porosity), MOS (moscovite) OF (iron oxide), OOI (ooid), PEL (pellet), PEO (peloid), Q-TER (terrigeneous quartz). (h) CONT (continental), CONT-AL (alluvial), CONT-LAC (lacustrine), MAR (marine). (p) = possible.

|

Genetic type (a) |

Gitologic type(b) |

Sample locality |

Sedimentary structure (c) |

Texture (d) |

Mineralogy (e) |

Skeletal grain, bioclasts(f) |

Porosity and non-skeletal (g) |

Formation environment (h) |

|

|

J2-2a |

0 |

OUR5 |

LCR, PER |

MUD |

mQ-CQ(70%), MQ, CAL-LF(10%) |

ESP-M, FOR, GAS(p), INS |

FEN, MOL, OF, CaCO3, |

MAR |

|

|

J2-2b |

0 |

OUR6 |

PER |

WAC |

mQ-CQ(65%), mQ(5%), CAL‑LF(10%) |

ESP-M(p), ESP-T, GAS, CHA-S, INS(p) |

FEN, PEO, OF, CaCO3, MO(p) |

|

|

|

J2-3 |

1 |

OUR7, OUR8 |

MLR, PER |

MUD, WAC |

mQ-CQ(75%), mQ(5%), CAL‑LF(5%) |

ESP-M(p), GAS, OST, FRAG-IND |

FEN, MOL, OF, CaCO3, MO(p) |

|

|

|

J3-1 |

0 |

FZ1 |

LCR |

MUD |

mQ-CQ(90%), MQ(<5%),CAL‑LF(<5%) |

OF, CaCO3 |

CONT-LAC or MAR |

|

|

|

4 |

FZ4 |

LAM |

MUD |

mQ-CQ(90%), MQ, CAL-LF |

CHA-O, CHA-S(p) |

OF |

|

||

|

J3-2 |

0 |

TN5 |

LAM, PER |

WAC, PAC |

mQ-CQ(70%), CAL-LF(5%) |

GAS, OST(p), CHA‑S(p), FRAG-IND |

MOL, OF, CaCO3, DOL |

|

|

|

J3-3 |

0 |

FZ2, FZ3 |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

|

|

|

1, 2, 3 |

FZ2 |

PER, BRE, |

MUD, WAC |

mQ-CQ(60-90%), MQ(<10%) |

GAS, BIV(p), CHA-O, CHA-S, FRAG-IND |

FEN, MOL, OF, PEO, INT, Q-TER, MO(p), CaCO3 |

|

||

|

FZ3 |

LAM |

PAC, GRN |

CAL-LF(<10%) |

|

|||||

|

4 |

FZ4 |

WAC |

mQ-CQ (85%), MQ, CAL-LF (5%) |

FRAG-IND |

OF, PEO |

|

|||

|

J3-4 |

0 |

ALC1 |

PER, LCR |

PAC |

mQ-CQ(50%), MQ(5%), CAL‑LF(5%) |

ESP-T, FOR(p), GAS, FRAG-IND |

MOL, OF, PEO, Q-TER, MO, OOI(p), MOS, CaCO3 |

MAR(p) |

|

|

GRN |

|

||||||||

|

C2s-6 |

4 |

TN1, TN2, TN4 |

LAM, PER(p) |

MUD |

mQ-CQ(90%), MQ(5%), CAL |

ESP-M, FOR(p), FRAG-BIO |

FEN, OF |

MAR |

|

|

IND-1 |

4 |

TN3, TN4 |

BRE, LAM |

PAC, GRN |

mQ-CQ(40%) MQ(<5%), CAL(10%) |

|

FEN, OF, Q-TER, MOS |

CONT |

|

|

IND-2 |

1 |

OUR4 |

BRE |

SAN |

Cq(10%) |

|

FEN(p), OF, Q-TER |

|

|

|

4 |

OUR3 |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

NOTS |

|

||

|

IND-3 |

4 |

TN4 |

PER |

MUD |

mQ-CQ(85%) |

CHA-S, GAS |

OF, CaCO3 |

MAR or CONT-LAC(p) |

|

Table 2. Technological categories and raw material types present in the layer 14 sample. For quartz and quartzite, technological categories are given according to field data.

|

Technological category |

Flint |

Quartz |

Quartzite |

Rock crystal |

Limestone |

Igneous rock |

Lydite |

Total |

|

Core |

11 |

46 |

19 |

|

|

|

|

76 |

|

Flake |

359 |

576 |

643 |

|

7 |

8 |

2 |

1595 |

|

Blade |

4 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

6 |

|

Bladelet |

7 |

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

8 |

|

Chip |

218 |

718 |

361 |

3 |

|

|

|

1300 |

|

Chunk |

3 |

8 |

5 |

|

2 |

|

|

18 |

|

Retouched tool |

29 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

|

|

46 |

|

Cobble |

|

9 |

13 |

|

|

|

|

22 |

|

Total |

631 |

1366 |

1052 |

3 |

9 |

8 |

2 |

3071 |

Based on their color, mineralogy, sedimentary structure and fossil content, two categories of flint could be identified in the sources located at the boundary between the Bajocian and Bathonian (J2-2, J2-3), and four in sources located in the Oxfordian (J3-1 to J3-4). The structure, texture, mineralogy and constituents of these flints are variable; often, such variation can be observed within a single nodule.

Cretaceous flint (C2s) and silcrete (Ind-1, 2) were found exclusively in siliciclastic deposits of the TSB.

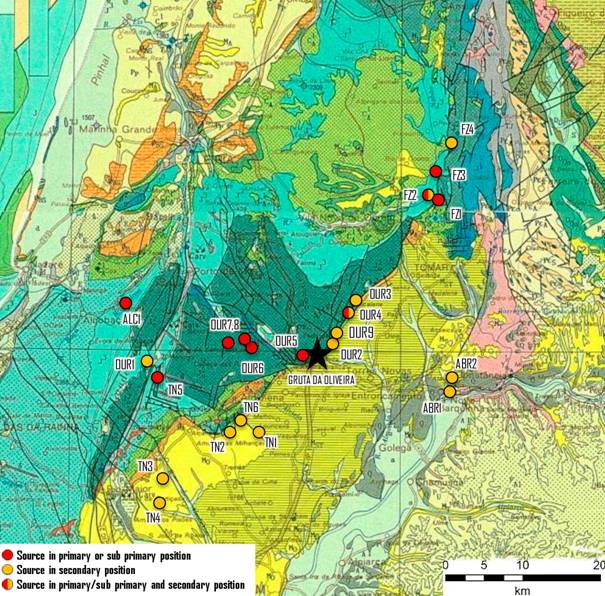

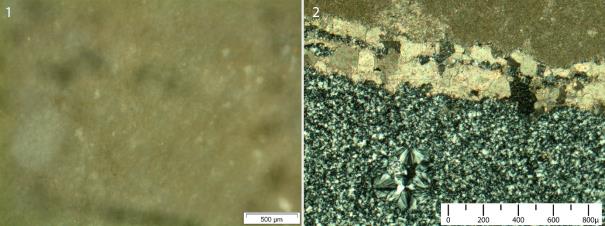

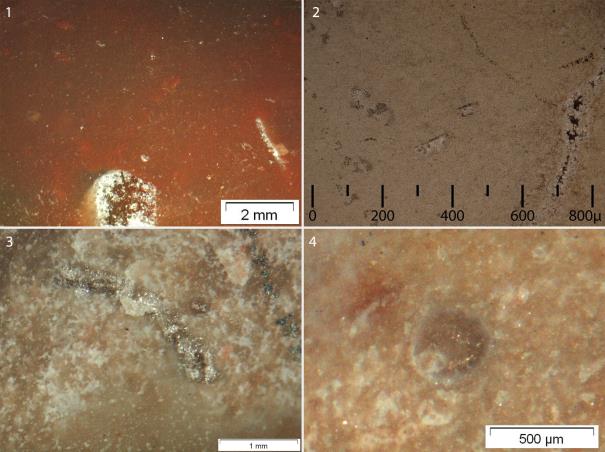

Two types of Upper Bajocian flint were identified (J2-2, J2-3). They can be easily differentiated by color, sedimentary structure and crystallization. Frequently they have a botryoidal cortex with impregnation of iron oxides. Liesegang-type structures, peloidal relicts and a bioclastic content are frequent. In the J2-2 type, the presence of numerous tectonic joints filled and recrystallized with iron oxides and micro-crystalline quartz allows the identification of regional variants. (Figure 3.)

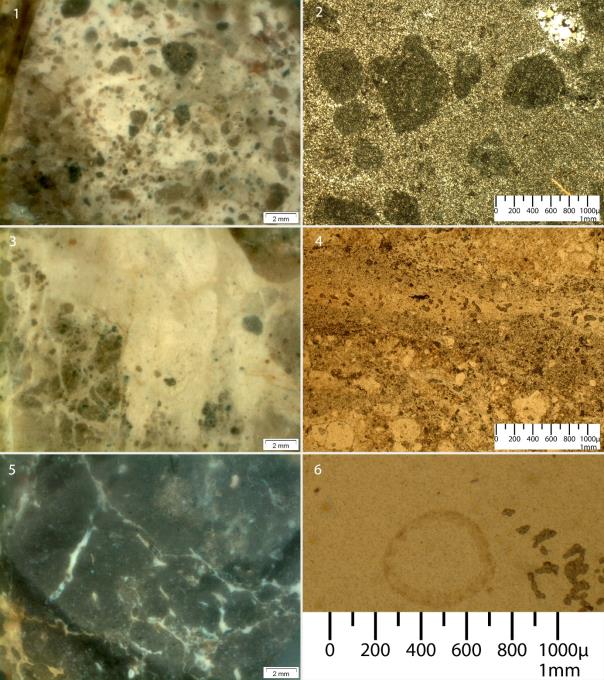

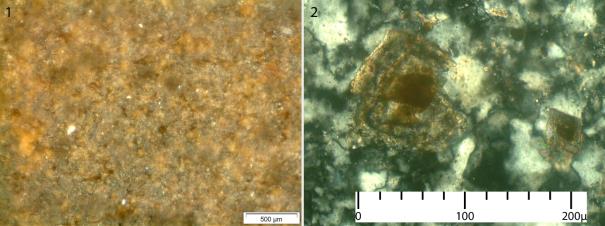

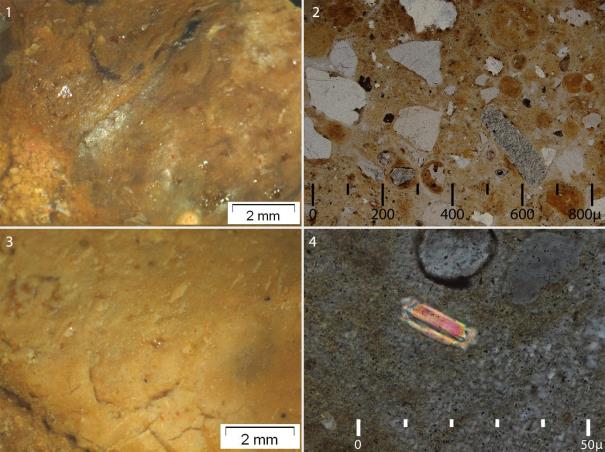

Four types of Oxfordian flint (J3-1 to J3-4), representing variation along the East-West axis of the CLM, could be identified. These flints are heterogeneous in structure, texture, mineralogy and constituents, often with such variation being visible in a single nodule. J3-1 and J3-3 (Figures 4 and 5) co-occur in the East, and it was not possible to determine if they were formed together or originate in different strata. J3-2 (Figure 6) and J3-4 (Figure 7) have the same “spotted” macroscopic aspect but distinct constituents; the first shows dolomitization associated with a silicification of the matrix, while the second contains detrital elements and distinctive skeletal remains.

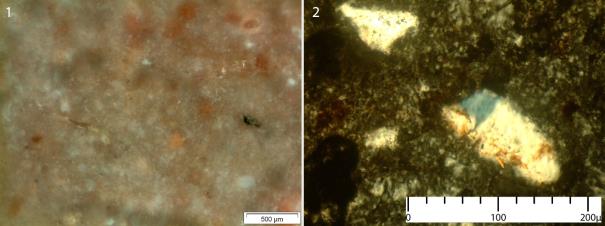

Cretaceous flint (C2s) and Cenozoic silcrete (ind-1,2) were found exclusively in the TSB, where they occur alongside the quartz, quartzite and lydite cobbles and sands making up the basin’s Lower Miocene siliciclastic deposits. Their secondary position is further supported by a clear rounded cortex with macroscopic impact marks caused by fluvial transport. Often, these Cretaceous flints are translucent and contain geodes with macroquartz crystals growth; they grade in color (from yellow to red and grey) but, mineralogically, are very homogeneous, frequently with rare or almost unnoticeable skeletal remains. Iron oxides concentrations are also frequent in the siliceous matrix (Figure 8). Cenozoic silcretes have a brecciated structure associated with lamination, frequently contain detrital quartz, and include no skeletal remains (Figure 9). The correspondence of the Late Cenomanian flint to this specific geological stage has been made by comparison with studies made in other localities (e.g., unit H of the Nazaré section (Callapez 1998)).

Figure 3. Bajocian flint´s macro and microscopic textures and constituents: 1. Liesegang concentric rings (scale bar = 2 mm); 2. General texture (scale bar = 500 µm); 3. Diaclase cemented by iron oxides and porosity filled by first and second generation micro and macro quartz (scale bar = 1 mm); 4. Triaxonic spicule recrystallized by micro-quartz (scale bar = 1 mm).

Figure 4. Oxfordian flints’ macro and microscopic textures and constituents; Type J3-2: 1. General texture (mudstone) (scale bar = 500 µm); 2. Spar calcite undergoing silicification at the contact between the silica matrix and the limestone (scale bar = 800 µm).

Figure 5. Oxfordian flints’ macro and microscopic textures and constituents; Genetic Type J3-3: 1., 3., 5. General heterogenic textures (mudstone to grainstone) (scale bar = 2 mm); 2. Brecciated sedimentary structure (scale bar = 1 mm); 4 Laminated sedimentary structure (scale bar = 1 mm); 5. Charophyta stem (scale bar = 1 mm).

Figure 6. Oxfordian flints’ macro and microscopic textures and constituents; Genetic Type J3-2: 1. General texture (scale bar = 500 µm); 2. Dolomite or calcite rhombohedra undergoing silicification (scale bar = 200 µm).

Figure 7. Oxfordian flints’ macro and microscopic textures and constituents; Genetic Type J3-2: 1. General texture (scale bar = 500 µm); 2. Detrital quartz embedded in the siliceous matrix (scale bar = 200 µm).

Figure 8. Macro- and microscopic textures and constituents of Cretaceous flints. Note the mudstone texture (1, 2) and bioclastic relicts (3, 4). (Scale bars: 1. 2 mm; 2. 500 µm; 3. 1 mm; 4. 500 µm.)

As the Almonda karst system is located at the boundary between the CLM and the TSB, the raw materials used by the Gruta da Oliveira Neanderthals reflect their natural availability within these two different structural units.

In the CLM, in situ and sub-primary Middle and Late Jurassic flint sources are found in geographically restricted outcrops or deposits, while the Miocene plains of the Tagus Basin feature widespread Cenozoic and Quaternary siliciclastic deposits with quartzite, quartz, lydite, silcrete and Cretaceous flints. The latter are spread over a large area to the SW, S, SE, E and NE, of the cave (although Cretaceous flints and silcrete only occur more than 10 km to SW). Therefore, only the Late and Middle Jurassic flint sources found to NE and W provide spatially precise indications of the Oliveira Neanderthals’ mobility.

Figure 9. Macro- and microscopic textures and constituents of Cenozoic silcretes. Note the brecciated structure (1-3) and detrital materials (2, 4).

Quartzite, lydite and quartz were collected and introduced in the cave as cobbles, boulders or large flakes, the latter probably produced at or close to the source. These rocks are widely distributed across hundreds of km of the TSB (Figure 10) and are abundantly available in the nearby TSB siliciclastic deposits. However, a fine-grained quartzite was preferentially selected for Levallois reduction, due to its homogeneity and excellent knapping qualities. Although it can be occasionally found across the Tagus basin, larger concentrations of this green- or red-colored quartzite were found in versant deposits located less than 5 km NE of the Gruta da Oliveira, implying that this raw material was probably locally collected. Elsewhere in the Almonda karst system, this fine-grained quartzite is rare or found in low proportions. The same applies to the other Paleolithic localities known in the TSB, where it is often altogether absent (as is the case, for example, in the Upper Paleolithic sites of the Rio Maior basin). The available data are not enough for a firm conclusion, but it seems likely that this particular type of fine quartzite can be used as a marker for the regional Middle Paleolithic.

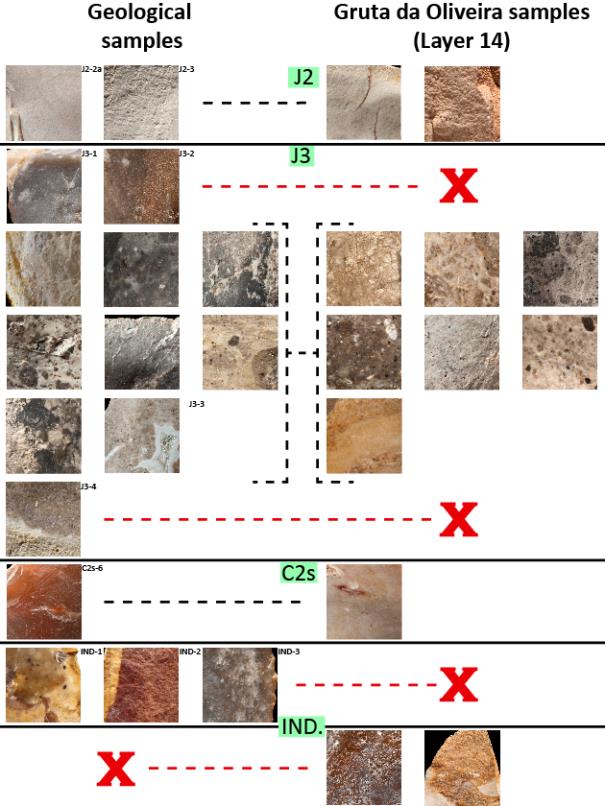

Concerning flint, the Cretaceous type (C2s), the most affected by weathering, represents more than 50% of the Oliveira sample, while Cenozoic silcretes (Ind) are rare (~1%), which can be explained by their geological scarcity in the siliciclastic deposits of the TSB. Both types of Middle Jurassic flint (J2-2 and J2-3) are present, but only one (J3-3) of the Late Jurassic flint types could be recognized (Figure 11 and 12).

Figure 10. Regional raw material sources, and raw material percentages in layer 14 of Gruta da Oliveira. In the overall pie chart, the “other” category includes limestone, rock crystal, lydite, and igneous rocks. [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

Using ethnographic data (Binford 1980), the presence in Oliveira of raw materials coming from sources less than 20 km can be interpreted as direct exploitation of the sources. As is the case with the evidence from the species represented among faunal remains (Zilhão et al. 2013), the lithic raw material data indicate an exploitation of both the highlands of the CLM and the plains of the TSB and are therefore consistent with procurement having been embedded in daily subsistence activities (Binford 1979).

Sixty-two percent of the Oliveira sample’s flint comes from the TSB, which can be related to the excellent knapping quality of its Cretaceous flint, abundantly represented in all prehistoric sites of the TSB but also found more than 150 km away in the Upper Paleolithic sites of the Côa Valley (Aubry 2005; Aubry et al. 2016; Aubry et al. 2012; Aubry & Mangado Llach 2003a; b; 2006; Aubry et al. 2004; Aubry et al. 2014; Mangado Llach 2002). Such a high percentage probably reflects long-term residence in the Tagus plains, with Gruta da Oliveira being used as a temporary camp where the good quality flint, brought from elsewhere, was eventually discarded, and local (<5 km) medium to poor quality Bajocian flint (12%) was used occasionally. Given the location of currently known sources, the significant percentage of Oxfordian flint (24%) could reflect some degree of seasonality within a large territory united by the natural corridor provided by the Nabão river valley, which, during the Upper Paleolithic (Aubry et al. 2012; Gameiro et al. 2008), linked the inhabitants of the CLM with those of the Sicó Massif to the North. Alternatively, it is also possible that groups primarily based in the CLM alternated use of the Gruta da Oliveira with groups primarily based in the TSB. The low percentage of cortex found on Oxfordian flint items (~13%; 35-40% in the other types) at least suggests that this raw material was processed differently, namely that it was brought in as pre-configured cores.

Figure 11. Flint’s distinctive features in the archeological sample: a. Bajocian flint. The iron filled diaclases pointed by arrow 1, and the concentric liesegang rings by arrow 2 are typical characteristics of flint type J2-2a (compare with Figure 3); b. botryoidal cortex of J2-3 type (Bajocian); c. and d. heterogenic “spotted like” texture of Oxfordian J3-3 type (compare with Figure 5, with a gastropod relict pointed by arrow 3; e. Upper Cenomanian flint with the siliceous reddish matrix turning rose and arrows pointing to a macroquartz filled geode (arrow 4) and a concentration of iron oxides (arrow 5) (compare with Figure 8); f. typical Upper Cenomanian flint in secondary position with rounded cortex impregnated by iron oxides (arrow 6). (Photos a., b. and f. by João Zilhão, b. to e. by José Paulo Ruas.) [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

The broader significance of these preliminary results and inferences requires a diachronic study of the lithic assemblages from Gruta da Oliveira and their comparison with other Middle Paleolithic sites, namely Gruta Nova da Columbeira, located 55 km to the SW, Gruta do Caldeirão, 25 km to the NE, close to the Nabão basin’s sources of J3-3 flint, and Buraca Escura located in the Sicó Massif, where the Oxfordian flint from the Nabão river is also present (Thierry Aubry, personal communication). Such study and comparisons are the object of ongoing research.

Figure 12. The flint and silcrete types recognized among the geological samples and their representation in layer 14 of Gruta da Oliveira. The cross means not present. Single image scale: 1 cm². (Photos by José Paulo Ruas.) [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

This study is a contribution to the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia’s project PTDC/HIS-ARQ/098164/2008 (“Middle Paleolithic Archaeology of the Almonda Karst System”), directed by João Zilhão, that led to a M.Sc. dissertation in Geoarcheology at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon; and to the Ph.D. Scholarship SFRH/BD/108396/2015, also funded by FCT. It would not be possible without the advice of Thierry Aubry, João Zilhão, and Xavier Mangado. Thank you for the knowledge shared and the friendship.

Almeida, F., Angelucci, D., Gameiro, C., Correia, J. & Pereira, T. 2004, Novos dados para o Paleolítico Superior Final da Estremadura Portuguesa: Resultados preliminares dos trabalhos arqueológicos de 1997-2003 na Lapa dos Coelhos (Casais Martanes, Torres Novas). Promontória, 2: 157-192. (in Portuguese) (“New data on the Late Upper Paleolithic of Portuguese Estremadura: Preliminary results of the 1997-2003 field seasons at Lapa dos Coelhos (Casais Martanes, Torres Novas, Portugal)”)

Almeida, F., Araújo, A.C. & Aubry, T. 2003, Paleotecnologia lítica: Dos objectos aos comportamentos. In: Paleoecologia humana e Arqueociências. Um programa multidisciplinar para a Arqueologia sob a tutela da Cultura (Mateus, J. & Moreno, M., Eds.), Trabalhos de Arqueologia Vol. 29, Instituto Português de Arqueologia, Lisbon: p. 299-349. (in Portuguese) (“Lithic paleotechnology: From the object to the behaviour”)

Angelucci, D.E. & Zilhão, J. 2009, Stratigraphy and Formation Processes of the Upper Pleistocene Deposit at Gruta da Oliveira, Almonda Karstic System, Torres Novas, Portugal. Geoarchaeology, 24(3): 277-310. doi:10.1002/gea.20267

Aubry, T. 2005, Etude de l’approvisionnement en matières premières lithiques d’ensembles archéologiques, remarques méthodologiques et terminologiques. In: Comportements des hommes du Paléolithique moyen et supérieur en Europe: territoires et milieux. Actes du Colloque du G.D.R. 1945 du CNRS, 8-10 janvier 2003 (Vialou, D., Renault-Miskovsky, J. & Patou-Mathis, M., Eds.), ERAUL Vol. 111, Université de Liège, Liège: p. 87-89. (in French) (“The sourcing of lithic raw-materials from archeological assemblages: Methodological and terminological remarks”)

Aubry, T., Gameiro, C., Mangado Llach, J., Luís, L., Matias, H. & do Pereiro, T. 2016, Upper Palaeolithic lithic raw material sourcing in Central and Northern Portugal: Reconstructing Long Distance Social Networks. Journal of Lithic Studies 3(2): 22 p. doi:10.2218/jls.v3i2.1436

Aubry, T., Luís, L., Mangado Llach, J. & Matias, H. 2012, We will be known by the tracks we leave behind: Exotic lithic raw materials, mobility and social networking among the Côa Valley foragers (Portugal). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 31(4): 528-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2012.05.003

Aubry, T. & Mangado Llach, J. 2003a, Interprétation de l'approvisionnement en matières premières siliceuses sur les sites du Paléolithique supérieur de la vallée du Côa (Portugal). In: Les matières premières lithiques en Préhistoire; table ronde internationale organisée à Aurillac, Cantal, du 20 au 22 juin 2002, Prehistoire du Sud-Ouest Vol. Supplément no. 5, Association Préhistoire du Sud-Ouest, Carcassone: p. 27-40. (in French) (“Interpretation of the procurement of siliceous raw-materials in the Upper Paleolithic sites of the Côa Valley (Portugal)”)

Aubry, T. & Mangado Llach, J. 2003b, Modalidades de aprovisionamento em matérias-primas líticas nos sítios do Paleolítico superior do Vale do Côa: Dos dados à interpretação. In: Paleoecologia humana e Arqueociências. Um programa multidisciplinar para a Arqueologia sob a tutela da Cultura (Mateus, J. & Moreno, M., Eds.), Trabalhos de Arqueologia Vol. 29, Instituto Português de Arqueologia, Lisbon: p. 340-342. (in Portuguese) (“The sourcing of lithic raw-materials from Côa Valley Upper Paleolithic sites: From data to interpretation”)

Aubry, T. & Mangado Llach, J. 2006, The Côa Valley (Portugal). From lithic raw materials characterization to the reconstruction of settlement patterns during the Upper Palaeolithic. In: Notions de territoire et de mobilité. Exemples de l’Europe et des premières nations en Amérique du Nord avant le contact européen; Actes de sessions présentées au Xº congrès annuel de l’E.A.A. 8-11 septembre 2004, Lyon (Bressy, C., Burke, A., Chalard, P. & Martin, H., Eds.), ERAUL Vol. 116, Université de Liège, Liège: p. 41-49.

Aubry, T., Mangado Llach, J., Fullola, J.M., Rosell, L. & Sampaio, J.D. 2004, The rawmaterial procurement at the Upper Palaeolithic settlements of the CôaValley (Portugal). In: New Data Concerning Modes of Resource Exploitation in Iberia. The Use of Living Space in Prehistory; papers from a session at the E.A.A. 6th Annual Meeting,10-17 September 2000, Lisbon (Smyntyna, O.V., Ed.), BAR International Series Vol. 1224, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 37-50.

Aubry, T., Mangado Llach, J. & Matias, H. 2014, Matérias-primas das ferramentas em pedra lascada da Pré-história do Centro e Nordeste de Portugal. In: Trânsito e proveniências de materiais geológicos: Abordagens sobre o Quaternário de Portugal (Dinis, P., Gomes, A. & Monteiro-Rodrigues, S., Eds.), APEQ - Associação Portuguesa para o Estudo do Quaternário, Coimbra: p. 165-192. (in Portuguese) (“The raw-materials of prehistoric knapped stone tools from the Center and Northeast of Portugal”)

Binford, L.R. 1979, Organization and formation processes: Looking at curated technologies. Journal of Anthropological Research, 35(3): 255-273. doi:10.1086/jar.35.3.3629902

Binford, L.R. 1980, Willow Smoke and Dogs Tails - Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation. American Antiquity, 45(1): 4-20. doi:10.2307/279653

Bisson, M.S., Burke, A., Meignen, L. & Burke, A. 2011, Moinhos and Mina do Paço; Middle Palaeolithic lithic chipping stations in the Sado Basin, Alentejo, Portugal. O Arqueólogo Português, 5(1): 359-394. URL: http://www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt/static/data/publicacoes/o_arqueologo_portugues/serie_5/volume_1/moinhos.pdf

Bressy, C. 2003, Caractérisation et gestion du silex des sites mésolitiques et néolitiques du Nord-Ouest de l’arc alpin. Une approche pétrographique et géochimique. BAR International Series Vol. 1114. Archaeopress, Oxford, 295 p. (in French) (“Characterization and management of flint in the Mesolithic and Neolithic sites of the NW Alpine arch. A petrographic and geochemical approach”)

Burke, A., Meignen, L., Bisson, M., Pimentel, N., Henriques, V., Andrade, C., Da Conceição Freitas, M., Kageyama, M., Fletcher, W., Parslow, C. & Guiducci, D. 2011, The Palaeolithic occupation of southern Alentejo: The Sado River Drainage Survey. Trabajos de Prehistoria, 68(1): 25-49. doi:10.3989/tp.2011.11057

Callapez, P.M. 1998, Estratigrafia e Paleobiologia do Cenomaniano-Turoniano. O significado do eixo da Nazaré-Leiria-Pombal. Ph.D. thesis at the Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, 478 p. (in Portuguese) (“Stratigraphy and Paleobiology of the Cenomanian-Turonian. Significance of the Nazaré-Leiria-Pombal axis”) URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10316/1780

Delfim de Carvalho, A., Oliveira, J.T., Pereira, E., Ramalho, M., Antunes, M.T. & Monteiro, J.H. 1992, scale 1:500.000, Carta Geológica de Portugal. Serviços Geológicos de Portugal, Lisbon.

Dunham, R.J. 1962, Classification of carbonate rocks according to depositional texture. In: Classification of carbonate rocks: A Symposium (Hamm, W.E., Ed.), Memoir (American Association of Petroleum Geologists) Vol. 1, American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG), Tulsa: p. 108-121.

Fernandes, P. & Raynal, J.-P. 2006, Pétroarchéologie du silex: Un retour aux sources. Comptes Rendus Palevol, 5(6): 829-837. (in French) (“The Petroarcheology of flint: Back to the sources”) doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2006.04.002

Fernandes, P., Raynal, J.-P. & Moncel, M.-H. 2008, Middle Palaeolithic raw material gathering territories and human mobility in the southern Massif Central, France: First results from a petro-archaeological study on flint. Journal of Archaeological Science, 35(8): 2357-2370. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.02.012

Gameiro, C. 2003, L’industrie lithique de la couche 3 de Lapa dos Coelhos (Torres Novas, Portugal). L’usage des matières premières et la spécificité du débitage lamellaire dans le Magdalénien Final de L’Estremadura portugais. DEA thesis at the UFR 03 Histoire de l'art et Archéologie, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, 67 p. (in French) (“The stone tool assemblage from level 3 of Lapa dos Coelhos (Torres Novas, Portugal). Raw-material usage and particularities of bladelet production in the Final Magdalenian of Portuguese Estremadura”)

Gameiro, C. 2012, La variabilité régionale des industries lithiques de la fin du Paléolithique supérieur au Portugal. Doctoral thesis at the UFR 03 Histoire de l'art et Archéologie, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, 485 p. (in French) (“Regional variability of the stone tool assemblages at the end of the Upper Paleolithic in Portugal”) URL: http://www.academia.edu/3154767/

Gameiro, C., Aubry, T. & Almeida, F. 2008, L’exploitation des matières premières au Magdalénien Final en Estremadura portugaise: Données des sites de Lapa dos Coelhos et de l’Abrigo dos Covões. . In: Espace et temps: Quelles diachronies, quelles synchronies, quelles échelles? Procedings of the UISPP meeting. 4-9 Setembro, Lisboa, 2006 (Aubry, T., Almeida, F., Araújo, A.C. & Tiffagom, M., Eds.), BAR International Series Vol. 1831, Archaeopress, Oxford: p. 57-67. (in French) (“Raw-material exploitation in the Final Magdalenian of Portuguese Estremadura: The data from the sites of Lapa dos Coelhos and Abrigo dos Covões”)

Gaspar, R. 2009, Estudo petroarqueológico da utensilagem lítica do sítio arqueológico Lajinha 8 (Évora, Portugal). Análise de proveniências. Master thesis at the Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, 52 p. (in Portuguese) (“Petroarcheological study of the stone tools from the site of Lajinha 8 (Évora, Portugal). Provenience analysis”) URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/5945

Gaspar, R., Pedro, J. & Mata, J. 2009, Estudo arqueopetrográfico da utensilagem lítica do sítio neolítico da Lajinha 8 (Évora). Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia, 12(1): 19-33. (in Portuguese) (“Petroarcheological study of the stone tools from the site of Lajinha 8 (Évora, Portugal)”) URL: http://www.patrimoniocultural.gov.pt/media/uploads/revistaportuguesadearqueologia/12_1/12_1artigos/019_034.pdf

Geneste, J.-M. 1985, Analyse lithique d’industries moustériennes du Périgord: Une approche technologique du comportement des groupes humains au Paléolithique moyen. Doctoral thesis at University of Bordeaux, Talence, 567 p. (in French) (“Lithic analysis of the Périgord Mousterian industries: A technological approach to the behavior of Middle Paleolithic human groups”)

Geneste, J.-M. 1991, L’approvisionnement en matières premières dans les systèmes de production lithique: La dimension spatiale de la technologie. Treballs d’Arqueologia, 1: 1-36. (in French) (“Raw-material procurement in lithic production systems: The spatial dimension of technology”)

Hoffmann, D.L., Pike, A.W.G., Wainer, K. & Zilhão, J. 2013, New U-series results for the speleogenesis and the Palaeolithic archaeology of the Almonda karstic system (Torres Novas, Portugal). Quaternary International, 294: 168-182. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.05.027

Jordão, P. 2010, Análise de proveniências de matérias-primas líticas da indústria de pedra lascada do povoado calcolítico de São Mamede (Bombarral). Master thesis at the Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, 119 p. (in Portuguese) (“Raw-material sourcing of the knapped stone tools from the São Mamede (Bombarral) Copper Age settlement”) URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8269

Leroi-Gourhan, A. 1964, Le Geste et la Parole. Vol. 1: Technique et langage. Albin Michel, Paris, 325 p. (in French) (“Gesture and Speech”)

Mangado Llach, J. 2002, La Caracterizacion y el Aprovisionamiento de los Recursos Abioticos en la Prehistoria de Cataluna: Las Materias Primas Siliceas del Paleolitico Superior Final y el Epipaleolitico. Doctoral thesis at the Departamento de Prehistoria, Historia Antigua y Arqueologia, University of Barcelona, Barcelona, 424 p. (in Spanish) (“Characterization and procurement of abiotic resources in the Preshistory of Catalonia: Siliceous raw-materials of late Upper Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic”)

Marks, A., Monigal, K. & Zilhão, J. 2001, The lithic assemblages of the Late Mousterian at Gruta da Oliveira, Almonda, Portugal. In: Les premiers hommes modernes de la Péninsule Ibérique. Actes du Colloque de la Comission VIII de l’UISPP, Vila Nova de Foz Côa, Octobre 1998 (Zilhão, J., Aubry, T. & Faustino Carvalho, A., Eds.), Trabalhos de Arqueologia Vol. 17, Instituto Português de Arqueologia, Lisbon: p. 145-154.

Marks, A., Shokler, J. & Zilhão, J. 1991, Raw Material Usage in the Palaeolithic. The Effects of Local Availability on Selection and Economy. In: Raw Material Economies among Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers (Montet-White, A. & Holen, S., Eds.), University of Kansas Publications in Anthropology Vol. 19, University of Kansas, Lawrence: p. 127-139.

Marks, A.E., Brugal, J.-P., Chabai, V.P., Monigal, K., Goldberg, P., Hockett, B., Peman, E., Elorza, M. & Mallol, C. 2002, Le gisement pléistocène moyen de Galeria Pesada (Estrémadure, Portugal): Premiers résultats. PALEO, 14: 77-100. (in French) (“The Middle Pleistocene site Galeria Pesada (Estramadura, Portugal): First results”) URL: http://paleo.revues.org/1408

Masson, A. 1979, Recherches sur la provenance des silex préhistorique. Méthode d’étude. Études Préhistoriques, 15: 29-40. (in French) (“Researching the provenience of Prehistoric flints. Study method”)

Masson, A. 1981, Pétroarchéologie des roches siliceuses. Intérêt en Préhistoire. Doctoral thesis no. 1035 at University Claude Bernard, Lyon I, Lyon, 101 p. (in French) (“The Petroarcheology of siliceous rocks. Its interest for Prehistory”)

Matias, H. 2012, O aprovisionamento de matérias-primas líticas na Gruta da Oliveira (Torres Novas). Master thesis at the Faculty of Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, 135 p. (in Portuguese) (“Lithic raw material procurement in Gruta da Oliveira (Torres Novas)”) URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10451/8207

Nabais, M. 2011, The neanderthal occupation of Gruta da Oliveira (Almonda karstic system, Torres Novas, Portugal). Analysis of the burnt bones. In: II Jornadas de Jóvenes en Investigación Arqueológica. JIA 2009, 6, 7 y 8 de Mayo de 2009, Madrid Vol. 1 (Moya Maleno, P.R., Charro Lobato, C., Gallego Lletjós, N., González Álvarez, D., González García, I., Gutiérrez Martín, F., Lozano Rubio, S., Marín Aguilera, B., Moragón Martínez, L., de la Peña Alonso, P., Sánchez-Elipe Lorente, M. & Martín, J.M.S., Eds.), Libros Pórtico, Madrid: p. 381-385.

Pereira, T., Andrade, C., Costa, M., Farias, A., Mirão, J. & Carvalho, A.F. 2016, Lithic economy and territory of Epipaleolithic hunter–gatherers in the Middle Tagus: The case of Pena d'Água (Portugal). Quaternary International, 412(A): 135-144. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.08.081

Richter, D., Angelucci, D.E., Dias, M.I., Prudêncio, M.I., Gouveia, M.A., Cardoso, G.J., Burbidge, C.I. & Zilhão, J. 2014, Heated flint TL-dating for Gruta da Oliveira (Portugal): Dosimetric challenges and comparison of chronometric data. Journal of Archaeological Science, 41: 705-715. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.09.021

Rottlander, R. 1975, Formation of Patina on Flint. Archaeometry, 17(1): 106-110. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1975.tb00120.x

Séronie-Vivien, M. & Séronie-Vivien, M.R. 1987, Les silex du Mésozoïque nord-aquitain. Approche géologique de l’étude des silex pour servir à la recherche préhistorique. Bulletin de la Société Linnéenne de Bordeaux Vol. 15, Supplement. Société Linnéenne de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, 135 p. (in French) (“North-Aquitanian Mesozoic flints. A geological approach to studying flints for Prehistoric research purposes”)

Shokler, J. 2002, Approaches to the sourcing of flint in archaeological contexts: Results of research from portuguese Estremadura. In: Interdisciplinary studies on ancient stone (Herman, J., Herz, N. & Newman, R., Eds.), Asmosia Vol. 5, Archetype Publications, London: p. 176-187.

Tixier, J., Inizan, M.-L. & Roche, H. 1980, Terminologie et techonologie. Préhistoire de la pierre taillée Vol. 1. Cercle de Recherches et d'Études Préhistoriques, Paris, 120 p. (in French) (“Terminology and Technology. The Prehistory of knapped stone”)

Veríssimo, H. 2004, Jazidas siliciosas da região de Vila do Bispo (Algarve). Promontória, 2: 35-47. (in Portuguese) (“Siliceous deposits in the region of Vila do Bispo (Algarve)”) URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.1/7469

Veríssimo, H. 2005, Aprovisionamento de matérias-primas líticas na Pré-História do concelho de Vila do Bispo (Algarve). In: O Paleolítico. Actas do IV Congresso de Arqueologia Penínsular, 14 a 19 de Setembro de 2004, Faro (Bicho, N., Ed.), Promontória Monográfica Vol. 2, Universidade do Algarve, Faro: p. 509-523. (in Portuguese) (“Lithic raw material procurement in the Prehistory of the Vila do Bispo (Algarve) municipality”)

Vignard, E. & Vacher, G. 1964, Altération des silex paléolithiques de Nemours sous l'influence des climats qui se sont succédés du Périgordien Gravettien au Tardenoisien locaux. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. Études et travaux, 61(1): 45-55. (in French) (“The alteration of Paleolithic flints from Nemours as a result of climate change through the local Perigordian-Gravettian to Tardenoisian sequence”) doi:10.3406/bspf.1964.3971

Zilhão, J. 1997, O Paleolítico Superior da Estremadura portuguesa. Colibri, Lisbon, 1159 p. (in Portuguese) (“The Upper Paleolithic of Portuguese Estremadura”)

Zilhão, J., Angelucci, D.E., Argant., J., Brugal, J.-P., Carrión, J.S., Carvalho, R., Fuentes, N. & Nabais, M. 2010, Humans and Hyenas in the Middle Paleolithic of Gruta da Oliveira (Almonda karstic system, Torres Novas, Portugal). In: 1a Reunión de científicos sobre cubiles de hiena (y otros grandes carnívoros) en los yacimientos arqueológicos de la Península Ibérica, Museo Arqueológico Regional, Alcalá de Henares: p. 298-308.

Zilhão, J., Angelucci, D.E., Aubry, T., Badal, E., Brugal, J.-P., Carvalho, R., Gameiro, C., Hoffmann, D., Matias, H., Maurício, J., Nabais, M., Pike, A., Póvoas, L., Richter, D., Souto, P., Trinkaus, E., Wainer, K. & Willman, J. 2013, A Gruta da Oliveira (Torres Novas): Uma jazida de referência para o Paleolítico Médio da Península Ibérica. In: Arqueologia em Portugal - 150 Anos (Arnaud, J.M., Martins, A. & Neves, C., Eds.), Associação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses, Lisbon: p. 259-268. (in Portuguese) (“Gruta da Oliveira: A reference site for the Middle Paleolithic of the Iberian Peninsula”)