New records of fishtail projectile points from Brazil and its implications for its peopling

Daniel Loponte 1, Mercedes Okumura 2, Mirian Carbonera 3

1. National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American

Thought. National Council of Scientific Research. 3 de Febrero St., 1378 (1426).

Buenos Aires, Argentina. Email:

dloponte@inapl.gov.ar

2. PPGArq. Department of Anthropology. National Museum. Quinta da Boa Vista. São

Cristóvão. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil- Email: mercedes@mn.ufrj.br

3. Center of Heritage Western of Santa Catarina (CEOM). University of the

Community of Chapecó / Unochapecó. John Kennedy St., 279 E, Chapecó, Santa

Catarina, Brazil. Email:

mirianc@unochapeco.edu.br

Fishtail or Fell projectile points constitute a specific design associated with early hunter-gatherers at the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary in many parts of South America, especially along the Pacific Coast, Patagonia, and the Argentine-Uruguayan Pampas. In this paper, we present new records of fishtail projectile points, recovered mainly in the southern states of Brazil, including design and metric descriptions, as well as some technological features, which are similar to other South American findings. The pieces are curated in different academic and private collections, some of which have been available a long time for study, but have not been published until now. This record doubles, at least, the known data available for these projectiles within the territory of Brazil. Finally, the importance of this widely distributed record within the context of the peopling of southern Brazil is briefly discussed.

Keywords: Fishtail projectile points; Paleoindian technology; early hunter-gatherers; Brazil

Las puntas de proyectil denominadas Cola de Pescado o Fell constituyen un diseño específico asociado con los cazadores-recolectores tempranos del límite Pleistoceno-Holoceno en diversas regiones de América del Sur, especialmente a lo largo de la costa del Pacífico sudamericano, la Patagonia y en las Pampas uruguayas y argentinas. En este trabajo, presentamos nuevos registros de estos cabezales líticos, recuperados principalmente en los estados del sur de Brasil. Incluimos además un somero análisis de los diseños presentes, sus propiedades métricas y algunas de las características tecnológicas presentes, las cuales son similares a otros registros sudamericanos. Las piezas se encuentran depositadas en diferentes colecciones académicas y privadas, pero hasta el momento no habían sido publicadas con alguna excepción. Este nuevo registro duplica como mínimo el número de ejemplares conocidos para el territorio brasileño. Finalmente, se discute brevemente la importancia del mismo dentro del contexto del poblamiento del sur de Brasil.

Keywords: Cola de pescado; tecnología paleosudamericana; cazadores-recolectores tempranos; Brasil

Neste artigo, apresentamos novas descrições de pontas do tipo “Rabo de Peixe”, recuperadas principalmente nos estados do sul do Brasil. Pontas do tipo “Rabo de Peixe” ou “Fell” apresentam uma forma específica associada a grupos caçadores-coletores da transição Pleistoceno - Holoceno em muitas partes da América do Sul, especialmente ao longo da costa do Pacífico, na Patagônia e nos Pampas da Argentina e Uruguai. No artigo são apresentadas imagens, dados métricos, e a caracterização tecnológica das peças. As pontas encontram-se em diferentes coleções acadêmicas e privadas, algumas delas disponíveis há muito tempo para pesquisa, porém apenas agora estão sendo apresentadas. Essas novas descrições dobram, no mínimo, o número desse tipo de ponta reconhecido em território brasileiro. Finalmente, a importância da ampla distribuição dessas pontas é discutida no contexto do povoamento do sul do Brasil.

Keywords: Pontas do tipo “Rabo de Peixe”; tecnologia Paleoíndia; caçadores-coletores; Brasil

Fishtail or Fell projectile points are related to early hunter-gatherer populations of the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary from Central and South America. Their chronology ranges from 11,000 to 10,000 uncalibrated radiocarbon years BP. The classical designs of these projectiles include a convex blade, rounded shoulders, and concave stem sides and bases (Mayer-Oakes 1963; 1986; Dillehay 2000; Miotti & Salemme 2005; Borrero 2006; Flegenheimer et al. 2013; Nami 2007; 2011a; 2011b; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; Nami & Heusser 2015). Technical features include a fluted channel on one or both faces of the stem, bifacial thinning with flake-scars over-passing the axis of symmetry and abrasion of stem’s sides. In some pieces, in the base of the stem, a beveled platform was done by abrasion in order to isolating a nipple to produce the fluting (Nami 2001; 2003; 2013; 2014a; 2014b). However, it has been recognized that Fell points present a great variability of forms and technological resources (Nami 2010; 2014a; 2014b; Flegenheimer et al. 2013). Not all projectiles have all technical and morphological attributes. For instance, the fluting is recognized in small number of cases. There are also examples of straight stems not related with the resharpening process (e.g., Nami 2013: Fig. 4j, l; Nami 2014a: Fig. 19b-c, 20). Thus, Fell points represent a continuum of morphometric variability, which is not surprising compared to most projectiles and artifacts of other archaeological contexts due to inherent variability in cultural transmission (Bettinger & Eerkens 1997; Eerkens & Lipo 2005; 2007; O’Brien & Lyman 2003a; 2003b; O’Brien et al. 2008; Shennan 2002).

The spatial range of fishtail projectile points (FTPPs) covers Central America and Western South America mainly, but recently points from Venezuela and Guyana were reported (Nami 2014a). In the South of the subcontinent, where it becomes narrower, FTPPs are distributed on the Atlantic slope, such as in Patagonia, Pampa, the Uruguayan plains, and southern Brazil (Figueira 1892; Serrano 1932; Bird 1938; 1969; Schobinger 1969; 1971; 1974; Mayer-Oakes 1963; Bell 1960; 2000; Chauchat & Zevallos Quiñones 1979; Bosch et al. 1980; Eugenio 1983; Nami 1987; 1992; 2007; 2011a; 2011b; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; Nami & Heusser 2015; Politis 1991; Núñez et al. 1994; Mujica 1995; Mazzanti 1999; 2002; 2003; Martínez 2001; Meneghin 2004; 2006; Grosjean et al. 2005; Jackson et al. 2007; Laguens et al. 2007; León Canales 2007; Díaz Rodríguez 2008; Briceño 2010; Miotti et al. 2010; Femenías et al. 2011; Maggard & Dillehay 2011; Flegenheimer et al. 2013; Patané Aráoz & Nami 2014; Loponte et al. 2015; Maggard 2015; Suárez 2015).

A recent analysis has gathered the available information about FTPPs in Brazil (Loponte et al. 2015). The observed spatial distribution supported the previous idea that the main area of concentration of these artifacts is located in the southern states (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and São Paulo), showing a continuous distribution with the Uruguayan record. The previous Brazilian sample analysis of 18 FTPPs and one preform also shows similar trends in technological behavior and patterns of design to the rest of the neighbouring regions (Loponte et al. 2015). Also, this latter contribution indicated the existence of other unpublished FTPPs curated in different academic and private collections, which could increase their known variability. Indeed, in the short time since this study, we are presenting here new specimens of FTPPs. Therefore, the main objective of this article is to present unpublished findings as well as technological and metrical data related to fishtail projectile points, including a short discussion about this growing record in relation to the peopling of southern Brazil.

The analyzed sample in this contribution includes 32 projectiles (Table 1, Figures 1, 2 and 3). Two of them (#17 and #19 of Table 1 and Figure 2) were originally presented by Becker (1966) (see also Beltrão 1974) and discussed by Loponte and colleagues (2015), but here we include for the first time good quality photos of these pieces. Another two points were presented by Costa (2009) and Marques (2010), both in unpublished Ph.D. dissertations, and certainly, practically unknown in the literature. Unfortunately, it was not possible to get good quality photos of a few pieces we are presenting here (#28 - #32; Table 1). The piece #1 is tentatively classified as FTPP. It lacks a concave stem and expanded base. Also, we were unable to determine the presence of abrasion at the base of the stem, but the blade morphology and bifacial thinning is typical of these points.

The typological assignment to FTPPs in the case of larger projectiles has no major problems, since most of them show the classical morphologies and technological features recognized within these pieces. However, broken or resharpened points with distorted morphologies have become a major problem in terms of recognizing their original designs. Therefore, misclassification must not be entirely ruled out for some of the recycled and smaller pieces. Below we discuss some of these cases in particular.

The sample includes some large specimens (Figure 1), which present the original shapes, unaffected or barely affected by the resharpening process, most of them with small stems. Indeed, in points over 100 mm in length, the blade is four times longer than their respective stems. The shape of the blades in these large pieces varies between an expanded and lanceolate design (Figure 1, e.g., pieces #1; #3, #4, #5 and #9) to a narrower and triangular one (e.g., pieces #2, #6, #7, #8). This variability in blade shape was also recorded in large pieces recovered throughout South America (Nami 2013; 2014a). In smaller points, both shapes of the blades (lanceolate and triangular) are recognized (Figure 2, pieces #17 and #20, vs. #16, #18 and #19, respectively). In fact, the presence of a triangular shape in small pieces is common in other regions (See Nami 2007: Fig 3-a; 2013: Fig. 3-d, h; 2014a: Fig. 18-a). The shoulders are rounded in some points (Figure 1, #1, #4), and straighter, close to 90° in most of them, even in heavily resharpened pieces (Figure 2, #19).

Table 1. Fishtail projectile points included in this article. Pieces 1 to 9 are presented in Figure 1. Pieces 10 to 19 are presented in Figure 2. Pieces 20 to 27 are presented in Figure 3.

Abbreviations: Obs. = observations.

Collections: IAP = Instituto Anchietano de Pesquisas; MAE-UFBA = Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade Federal da Bahia; MAE-USP-CRAMN = Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo - Centro Regional de Arqueologia Mario Neme; MAE-USP = Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo; MAE-USP-CPA = Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo - Coleção Plínio Ayrosa; MAE-USP-CvK = Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia da Universidade de São Paulo - Coleção von Koseritz; MAI = Museu de Arqueologia de Iepê; Marsul = Museu Arqueológico do Rio Grande do Sul; Marsul-CW = Museu Arqueológico do Rio Grande do Sul - Coleção Waslawick; MASJ-CGT = Museu Arqueológico de Sambaqui de Joinville - Coleção G. Tiburtius; MEF = Museu Escolar dos Franciscanos; MMJ = Museu Municipal de Jahu; MP = Museu Paranaense; MC- PUC = Memorial do Cerrado - Pontifícia Universidade Católica; CEPA-UFPR = Centro de Estudos e Pesquisas Arqueológicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná; MN-UFRJ = Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro; MN-UFRJ-CGM = Museu Nacional da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - Coleção Gualter Martins; CEPA-UNISC = Centro de Ensino e Pesquisas Arqueológicas - Universidade de Santa Cruz do Sul; PC = Private collection.

States: MT = Mato Grosso; SC = Santa Catarina; PR = Paraná; SP = São Paulo; AM = Amazônia; RS = Rio Grande do Sul; GO = Goiás; BA= Bahia.

Raw materials: Ch = chert; AR = acid rock; SS = silicified sandstone; Q = quartz; B = basalt; SM = silicified mud; (?) = possibly; ? = unknown.

|

Piece # |

Original label |

Collection |

State |

location |

Site |

Raw material |

Fluting |

Obs. |

References |

Figure |

|

1 |

X424 |

MAE-USP-CPA |

MT |

Poxoréu |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||

|

2 |

030.3/101 |

MAE-USP |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

3 |

RGA112 030-4 |

MAE-USP-CRAMN |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

4 |

1383 |

CEPA-UNISC |

MT |

Norterlândia |

Chert |

Yes |

This work |

1 |

||

|

5 |

113 |

MAE-USP-CvK |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

6 |

136 |

MAE-USP-CvK |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

7 |

151 |

MAE-USP-CvK |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

8 |

030.5/ RGA 127 |

MAE-USP |

Chert |

No |

This work |

1 |

||||

|

9 |

NN |

PC |

SC |

Mondaí |

Acid rock |

No |

This work |

1 |

||

|

10 |

18492 |

MN-UFRJ |

Quartz |

No |

This work |

2 |

||||

|

11 |

309 |

MASJ-CGT |

PR |

Reserva |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

||

|

12 |

MAI |

SP |

Iepê |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

|||

|

13 |

160 |

MAE-USP-CvK |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

||||

|

14 |

SN1 |

MP |

PR |

Piraquara |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

||

|

15 |

293 |

MASJ-CGT |

PR |

Reserva |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

||

|

16 |

840.0010 |

MMJ |

SP |

Jau |

Chert |

No |

This work |

2 |

||

|

17 |

Ft-1 (60901) |

MN-UFRJ-CGM |

SP |

Rio Claro |

Chert |

No |

Beltrao (1974) |

3 |

||

|

18 |

10 |

MASJ-CGT |

SC |

Taió |

Chert |

No |

This work |

3 |

||

|

19 |

Ft-3 (70087) |

MN-UFRJ-CGM |

SP |

Rio Claro |

Chert |

No |

Beltrao (1974) |

3 |

||

|

20 |

971 |

Marsul |

RS |

Alegrete |

RS-I-47 Lageado Grande 4 |

Silicified sandstone |

No |

This work |

3 |

|

|

21 |

2599-01 |

Marsul-CW |

RS |

Nova Petrópolis |

Basalt |

No |

This work |

3 |

||

|

22 |

2599(21) |

Marsul-CW |

RS |

Nova Petrópolis |

Chert |

Yes |

reused |

This work |

3 |

|

|

23 |

1174 |

CEPA-UFPR |

PR |

Foz do Iguaçu |

PR FI 124 |

Chert |

No |

stem |

This work |

3 |

|

24 |

3100 |

CEPA-UFPR |

PR |

Curitiba |

PR CT 59 Rio Pequeno 1 |

Chert |

No |

stem |

This work |

|

|

25 |

1821 |

CEPA-UFPR |

PR |

Curitiba |

PR CT 48 Cotovelo do Passaúna 3 |

Quartz |

No |

reused |

This work |

|

|

26 |

A281 |

IAP |

RS |

Ivoti |

RS-C-43 Capivara |

Silicified sandstone (?) |

No |

reused |

This work |

|

|

27 |

A290 |

IAP |

RS |

Ivoti |

RS-C-43 Capivara |

Basalt (?) |

No |

reused |

This work |

|

|

28 |

NN |

PC |

AM |

Maués |

Silicified mudstone |

No |

Costa (2009) |

|||

|

29 |

NN |

MAE-UFBA |

BA |

Bahia State |

? |

Marques (2010) |

||||

|

30 |

NN |

PC |

SC |

Corupá |

? |

This work |

||||

|

31 |

NN |

MEF |

SC |

São Francisco do Sul |

? |

Chiari (2001) |

||||

|

32 |

NN |

MC-PUC |

GO |

Goiás State |

Yes |

This work |

In large points, with few exceptions (e.g., Figure 1, #1), the stems show the classic expanded base, presenting concave sides. In some resharpened projectiles, the sides of the stems are straight (Figure 2, #15, #20), but this does not happen in the majority of the resharpened pieces (Figures 2 and 3). The basal ears or auricles (in the sense of Cambron & Hulse 2012) are divergent and pointed in several stems, presenting a quite regular concavity depth, between 1.5 to 3 mm. Pieces #4 (Figure 1) and #21 (Figure 3) show a straight base. While this is not common, there are several examples of this design in resharpened FTPPs (Nami 2007: Fig. 3-a, 5-a; 2013: Fig. 3-u; Flegenheimer et al. 2013: Fig. 21.6 - 21.11).

Figure 1. Fishtail projectile points discussed in the text (scale bar = 3 cm). [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

The presence of fluting is highly variable in FTPPs (Nami 2007; 2013; Hermo & Terranova 2012; Flegenheimer et al. 2013). Within the pieces analyzed here, only two stems are fluted (#4, #22). The latter specimen was reused or reclaimed as an end scraper, where the fluting is deflected from the morphological axis. While the sample size is still small, the trend on the Brazilian record shows a discrete incidence of this technique (Loponte et al. 2015).

Figure 2. Fishtail projectile points discussed in the text (scale bar = 3 cm). [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

Figure 3. Fragments and small pieces of FTPP (scale bar = 3 cm). [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

Pieces presenting a length greater than 80 mm show flake-scars reaching or over-passing the axis of symmetry of the points due to bifacial thinning. In some cases, percussion scars are partially covered by short retouches of 5 mm in width or narrower in order to finalize the pieces. There are some 5-6 mm retouches reaching up to 20 mm (pieces #3 and #6, Figure 1), beginning at the edge and ending in the center of the pieces.

Longitudinal cross-sections in points greater than 80 mm are always biconvex, probably related to the use of thinned bifaces as blanks (Nami 2001; 2003; 2015b). On the other hand, plane-convex cross-sections are observed in smaller pieces. In fact, in point #16, made from a thin flake, the ventral face is substantially flat, with no retouches in part of the blade, similar to other projectiles recovered in other areas of South America (Flegenheimer et al. 2010; Nami 2015b).

The morphological variability observed in the sample, also recognized in many other regions in South America, has been attributed to differences between regions and individuals, to the hunting of different prey sizes (Nami 2014a), and to changes due to resharpening (Nami 1990; 1998; 2000; 2001; 2003; 2007; 2010; 2011a; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; 2015b; Politis 1991; Suárez 2004; Baeza & Femenías 2005; Flegenheimer et al. 2010; 2013; Castiñeira et al. 2011). Additionally, there could also be a dimensional variability associated with the type of raw material used. In fact, for example, within the 32 points analyzed here, and among the 15 previously published (Loponte et al. 2015), only one large piece is made of quartz (Figure 2, #10). Even a preform of this raw material was intended to produce a projectile of no more than 55 mm in length (Loponte et al. 2015). Quartz, except hyaline type, is a raw material of lower quality than chert, basalt, and chalcedony. One of the characteristics presented by the different varieties of quartz are fissures (Nami 2015a). This is one of the properties that may have led to its use only in the manufacture of smaller projectiles in many contexts (see Nami 2009). Besides, it is clear that the sizes of the available nodules or blocks must be analyzed in each particular area, which could be an additional restriction to produce large projectiles made of quartz.

In addition to large projectiles, the collection includes pieces with a high degree of reactivation such as pieces #19, #20 (Figure 2) and #21 (Figure 3), where the blades, the stems, and eventually their symmetries were extremely modified. This also includes fragmented and recycled or reclaimed pieces (see Figure 3). Some of them are so resharpened that the FTPP design is barely recognizable. This is the case for the four end scrapers shown in Figure 3 (#22, #25, #26, #27). These recycled or reclaimed artifacts are less than 20 mm in length, except piece #22 (29 mm), which is undoubtedly a FTPP, since its fluted channel, deflected from its morphological axis, is noticeable in the base. The reuse or recycling of fishtail points as “stemmed end-scrapers” has been recently reported in sites from northern Uruguay, near the Brazilian border, quite similar to these pieces (Nami 2015b; 2015c; see also Oliveira 2014). However, due to the extremely modified morphologies of these pieces, it is not unlikely that some of them, as claimed by this author, could be reclaimed points from other archaeological cultures (such as “Umbu Tradition” - Miller 1969; Okumura & Araujo 2013; 2014).

We were able to identify the raw materials in 28 specimens within the collection. Chert (sensu Rapp 2002) was used in most of the cases (71%), as observed before in Brazilian FTPPs (Loponte et al., 2015), followed by silicified sandstone, basalt, and quartz. All these raw materials can be found in numerous outcrops in many areas of southern Brazil (Amaral 1971; Stevaux et al. 1986; Wildner et al. 2006). On the contrary, other rocks often used in Uruguayan FTPPs such as silicified limestone (Nami 2013) were not identified in the sample, although is highly probable to find it in pieces recovered near the Brazilian-Uruguayan border.

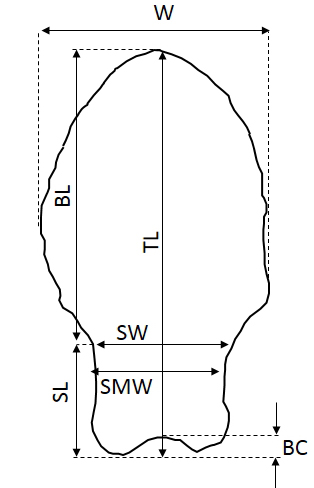

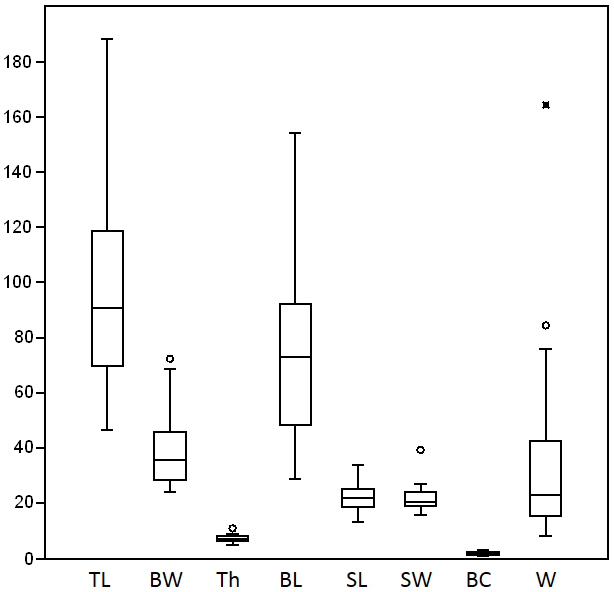

There is a growing literature discussing the morphotypes and the metrics of FTPPs (Borrero 1983; Nami 1990; 1998; 2000; 2001; 2003; 2007; 2010; 2011a; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; Suárez 2004; Baeza & Femenías 2005; Flegenheimer et al. 2010; 2013; Castiñeira et al. 2011; Loponte et al. 2015). Some of these references include traditional morphometrics, while others focus on geometric morphometric analysis. Here we present the preliminary results including key measurements for each artifact (Figure 4) and metric relationships (Table 2). A geometric morphometric analysis is a work in progress.

Figure 4. Key measurements described in the text. TL = total length. W = width (maximum). BL = blade length. SL = stem length. SW = stem width (maximum). SMW = stem width (minimum). BC = basal concavity. Th = Maximum thickness.

The standard lengths of FTPPs are usually of medium size (between 50 and 60 mm) (Nami 2007; 2011a; 2011b; 2013; 2014a; 2014b; Castiñeira et al. 2011; Flegenheimer et al. 2013; Loponte et al. 2015). However, the sample analysed here includes some large pieces above 100 mm. This is the reason why the mean length (98.4 mm) is greater than the reported average of these projectiles, and both the length and width are highly scattered (Figure 5). The maintenance process focused mostly on the blade length resulting in an almost perfect positive correlation with the total length, and secondly in the blade width (Table 3). This process of resharpening is responsible for the relative compression of the blade during the life history of these points (Suárez 2004; Castiñeira et al. 2011). In fact, blade length and blade width are the linear measurements with the highest variation (CV= 44.6% and 35.5% respectively, Table 2, see also Loponte et al. 2015). On the other hand, thickness, stem length, and width were less affected by the maintenance process, as is usually seen in projectile points (Flenniken & Raymond 1986; Nami 1990; 2000; Bettinger & Eerkens 1999) (Table 2 and Figure 5). Stem length and width have a strong, significant, and positive correlation (see Table 3). The ratio between these two dimensions shows a value close to 1 (1.0 ± 0.13); a similar situation is described in other Brazilian and Uruguayan samples of FTPPs (Baeza & Femenías 2005; Loponte et al. 2015).

Table 2. Measurements of FTPPs discussed in the text. TL= total length. BW= blade width (maximum). Th = thickness (maximum). BL= blade length. SL= stem length. SW= stem width. BC= basal concavity

|

# |

TL |

BW |

Th |

BL |

SL |

SW |

BC |

Weight |

|

1 |

188.2 |

72.4 |

11.0 |

154.1 |

34.0 |

39.4 |

164.2 |

|

|

2 |

170.0 |

59.0 |

8.0 |

139.4 |

30.6 |

24.8 |

||

|

3 |

141.0 |

47.8 |

7.6 |

115.0 |

26.0 |

24.6 |

2.0 |

76.0 |

|

4 |

133.9 |

68.8 |

8.6 |

108.6 |

25.3 |

26.9 |

84.5 |

|

|

5 |

121.2 |

35.8 |

7.3 |

94.2 |

27.0 |

24.7 |

2.5 |

|

|

6 |

110.6 |

31.9 |

6.6 |

85.6 |

25.0 |

19.0 |

3.0 |

28.5 |

|

7 |

108.7 |

44.2 |

7.0 |

85.7 |

23.0 |

19.2 |

2.0 |

27.5 |

|

8 |

104.0 |

38.0 |

7.0 |

83.4 |

20.6 |

20.4 |

||

|

9 |

101.1 |

46.2 |

79.3 |

21.8 |

23.1 |

2.1 |

||

|

10 |

92.5 |

36.6 |

8.6 |

73.2 |

19.3 |

20.9 |

3.0 |

31.6 |

|

11 |

88.7 |

35.2 |

9.1 |

72.8 |

15.9 |

17.7 |

26.1 |

|

|

12 |

87.5 |

33.1 |

65.5 |

22.0 |

19.8 |

2.5 |

||

|

13 |

81.2 |

28.3 |

6.8 |

58.1 |

23.1 |

19.3 |

1.0 |

18.2 |

|

14 |

74.9 |

35.9 |

6.6 |

51.3 |

23.6 |

23.4 |

1.0 |

19.8 |

|

15 |

76.2 |

25.9 |

6.6 |

62.9 |

13.3 |

16.6 |

15.5 |

|

|

16 |

68.1 |

36.1 |

8.0 |

47.3 |

20.8 |

21.7 |

1.5 |

18.4 |

|

17 |

65.0 |

24.0 |

8.0 |

44.5 |

20.4 |

19.0 |

14.9 |

|

|

18 |

60.7 |

27.3 |

6.5 |

42.3 |

15.1 |

15.7 |

11.5 |

|

|

19 |

48.0 |

28.5 |

4.9 |

28.7 |

18.5 |

21.0 |

2.0 |

8.2 |

|

20 |

46.7 |

25.4 |

29.5 |

17.2 |

18.5 |

|||

|

N |

20 |

20 |

17 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

10 |

14 |

|

Min |

46.7 |

24.0 |

4.9 |

28.7 |

13.3 |

15.7 |

3.0 |

8.2 |

|

Max |

188.2 |

72.4 |

11.0 |

154.1 |

34.0 |

39.4 |

1.5 |

164.2 |

|

Mean |

98.4 |

39.0 |

7.5 |

76.1 |

22.1 |

21.8 |

2.1 |

38.9 |

|

Stand. dev |

37.9 |

13.8 |

1.4 |

33.9 |

5.1 |

5.1 |

0.7 |

42.6 |

|

Geom. mean |

91.9 |

37.1 |

7.4 |

69.0 |

21.6 |

21.3 |

1.9 |

26.8 |

|

Median |

90.6 |

35.9 |

7.3 |

73.0 |

21.9 |

20.7 |

2.0 |

23.0 |

|

25 percentile |

69.8 |

28.4 |

6.6 |

48.3 |

18.7 |

19.0 |

1.4 |

15.4 |

|

75 percentile |

118.6 |

45.7 |

8.3 |

92.1 |

25.2 |

24.3 |

2.6 |

42.7 |

|

Coeff. Var. (%) |

38.5 |

35.5 |

17.9 |

44.6 |

23.0 |

23.4 |

35.2 |

109.6 |

As pointed out before, part of the observed variability of the total length is due to the modification of the original designs by maintenance processes. Some authors have observed the probable existence of two original weights, one consisting of small pieces of ~6 g and the other large pieces between 26.5 and 36.7 g (Flegenheimer et al. 2010). There is not much information available for comparison. However, a preform recovered in Orleans (Santa Catarina State) suggests the manufacture of pieces of 10-16 g (Loponte et al. 2015) and other preform weights are probably in between these two suggested thresholds (e.g., Nami 2015b). Our sample presents a geometric mean of ~27 g, with three outliers (>76 g). Pieces below 15.4 g (see the percentiles in Table 2) are rare, and no projectiles weigh less than 8 g, at least none which were not heavily affected by resharpening processes (see also Loponte et al. 2015).

Figure 5. Size and weight distributions of the sample. Abbreviations: TL = total length; BW = blade width; Th = Maximum thickness; BL = blade length; SL = stem length; SW = stem width; BC = basal concavity; W = weight. All measurements are expressed in mm, except W (weight), which is expressed in g.

Table 3. Correlation of the values for the main metric variables considered in the present study

|

Total length |

Total width |

Blade length |

Stem length |

Stem width |

||||||

|

rs |

p |

rs |

p |

rs |

p |

rs |

p |

rs |

p |

|

|

Total width |

0.83 |

0.0002 |

||||||||

|

Blade length |

0.99 |

0.0001 |

0.81 |

0.002 |

||||||

|

Stem length |

0.82 |

0.0001 |

0.69 |

0.001 |

0.7 |

0.001 |

||||

|

Stem width |

0.69 |

0.001 |

0.79 |

0.003 |

0.62 |

0.004 |

0.83 |

0.0001 |

||

|

Thickness |

0.52 |

0.03 |

0.56 |

0.01 |

0.35 |

0.16 |

0.34 |

0.17 |

0.44 |

0.07 |

Previous analysis of FTPP distribution in Brazil shows a main concentration in the southern states, with an isolated point recovered in Bahia (Northeast Brazil) (Nami 2010; Loponte et al. 2015). The present sample shows a similar trend. Almost 90% of the pieces analyzed here were recovered from southern Brazil (São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul). However, our sample increases the range of FTPPs, due to the identification of points from northern settings. There are two points from Mato Grosso (#1, #4, Figure 1), the last one presenting fluting. Moreover, there is a specimen curated at Memorial do Cerrado in Goiás, probably recovered from this region (piece #32, Table 1). Unfortunately there are no good quality photographs of that specimen, which is a medium sized point, with the classical morphology of a FTPP (lanceolate blade, slightly rounded shoulders, concave stem, basal concavity, divergent auricles and fluting). In any case, these three pieces expand the distribution of FTPPs in Brazil northwards (Figure 7), making the FTPP recovered in Bahia State more reasonable (Nami 2010), which at that moment was completely isolated from the main area of these projectiles in Brazil. Moreover, piece #28 (curated at MAE-UFBA) was probably also recovered in this state. A possible fourth specimen, which has the formal shape of a FTPP, was located in Amazonia State in a private collection. It was briefly described by Costa (2009: Fig. 15), who mentions its similarity with FTPPs. It is included in this paper as piece #27 (Table 1). The author does not present any metric data, but a photograph taken by H. Lima (without scale) was available and reproduced here (Figure 6). This projectile is made of silicified mudstone, available in the Amazonas River basin (Costa 2009: 34). Finally, it must be mentioned a fluted point published by Meggers (2007: Fig. 4.9) and identified as a FTPP by Nami (personal communications with Nami in 2015), recovered in the Upper Rio Negro river, Amazônia State.

Figure 6. Projectile point recovered at Maués (Amazônia State). Image taken and modified from Costa (2009: 34).

Figure 7. Distribution of FTPPs. Pieces 1 to 32 according to Table 1: 1 = Poxoréu (AM); 4 = Nortelândia (MT); 9 = Mondaí (SC); 11 = Reserva (PR); 12 = Iepê (SP); 14 = Piraquara (PR); 15 = Reserva (PR); 16 = Jau (SP); 17 = Rio Claro (SP); 18 = Taió (SC); 19 = Rio Claro (SP); 20 = Alegrete (RS); 21, 22 = Nova Petrópolis (RS); 23 = Foz do Iguaçu (PR); 24, 25 = Curitiba (PR); 26, 27 = Ivoti (RS); 28 = Maués (AM); 29 = Bahía State; 30 = Corupá (SC); 31 = São Francisco do Sul (SC); 32 = Goiás State; 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 13 = unspecified. Pieces 33 to 50 according to Loponte et al. (2015): 33 = Lagoa Mirim (RS); 34 = RS-I-69 (RS); 35 = Montenegro (RS); 36 = RS-C-43 (RS); 37 = Rio Grande do Sul State; 38, 39 = Orleans (SC); 40 = Jaguaruna (SC); 41 = Irani River (SC); 42 = Itapiranga (SC); 43 = Jusante (PR); 44 = PR-FI-124 Santa Helena (PR); 45 = Apiaí (SP); 46, 47, 48 = Rio Claro (SP); 49 = Abrigo de Santana do Riacho (MG); 50 = Bahia State; 51 = Rio Negro valley (AM) (Meggers 2007). State codes: RS = Rio Grande do Sul; SC = Santa Catarina; PR = Paraná; SP = São Paulo; MG = Minas Gerais; BA = Bahia; GO = Goiás; MT = Mato Grosso; AM = Amazônia. [View a higher resolution version of this image.]

There is significant agreement that FTPPs were produced by Paleo South American populations at the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary, and that these groups were distributed in many regions of the subcontinent, including southern Brazil (Rohr 1966; Beltrão 1974; Schobinger 1974; Chmyz 1978; Collet 1980; 1987; Prous 1992; Politis 1991; Prous & Fogaça 1999; Nami 2010; 2013; Silva Lopes & Nami 2011; Dillehay 2012). However, one of the main problems here is the lack of stratigraphic contexts related to FTPPs. There are only two sites in this area with reliable chronology older than 10,000 14C years BP (Bueno et al. 2013). Both sites are located on the left bank of the Uruguay River (Rio Grande do Sul State). In one of them, named RS-I-69 (Laranjito), a projectile recently identified by Nami (2013) as a FTPP was recovered from a level ranging from 10,900 to 10,200 14C years BP. It is important to point out that according to Miller’s drawing (1987: 60) the excavation of the oldest levels was reduced to a test-pit. Therefore, the available sample of these levels is quite small. The other site is RS-I-66 (Milton Almeida), which has only one radiocarbon date of 10,810 ± 275 14C years BP (Miller 1987). The archaeological context was published in a generic way, and certainly needs a reexamination, especially when one projectile point made of quartz, recovered from the deepest level, looks like a FTPP (Miller 1987: 12, Fig. 12d). This specimen is quite similar to those published by Nami (2014a: Fig. 9-e-b & Fig. 11-b), which are close to the stage of “saturated resharpening” (Nami 2013).

There is a third example of a FTPP recovered from an excavation in southern Brazil. This piece came from the base of the undated stratigraphic sequence of the RS-C-43 site, located in the Caí River Valley, excavated by Pedro Ignácio Schmitz, where “one atypical projectile point…represented by the lanceolate shape with a fish tail style stem” was recovered (Dias 2012: 16). This finding was interpreted as an indicator of “possible cultural exchanges with populations of the extreme South America Southern Cone in the Early Holocene” (Dias 2012: 16), but not as a local product. No other information is available such as the raw material used or other issues, which could allow us to discard it as being locally manufactured. Consequently, it is important for the analysis of this record, not only to recognize the existence of FTPPs in stratigraphic positions, but also to get radiocarbon dates. This “atypical” projectile point, which it could be identified as a probable fragment of a FTPP (Loponte et al. 2015) was recovered from the same site as pieces #26 and #27 (Table 1 and Figure 3).

It is quite clear that, besides a methodological problem, we have few reliable contexts of proper antiquity that we need in the area to identify these early hunter-gatherers in stratigraphic positions, at least in the territory that we can consider the core area of their distribution in Brazil, which is in the southern states (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná). It is also important to include in this discussion in the future other contexts of the late Pleistocene, which, even though lacking projectile points, may be included within the Fell technological system, as it happens in other regions of South America (Nami 2014a). These assemblages are made of immediate local raw materials (sensu Meltzer 1989) and present expedient and versatile tools (sensu Nelson 1991). By contrast, curated artifacts as projectiles made of distant local raw materials (sensu Meltzer 1989) tended to be maintained and then reused as knives and scrapers (see Nami 2015b), presenting low discard rates, which further complicates the identification of these sites. All these assemblage properties can be considered as representing an initial stage of exploration or the colonization of new environments (Borrero 1994). Such early moments are recognizably problematic to identify archaeologically and this may indeed explain the difficulty of finding a stratigraphic record related to Fell points in southern Brazil as well as in many other regions. In contrast, local archaeologists easily identify sites with a different type of points called “Umbu,” chronologically related to the Early to Late Holocene, and which mostly correspond to a period of effective occupation of the territory (sensu Borrero 1994). Whatever the interpretation of the Brazilian record, we cannot ignore the existence of FTPP and their continuous distribution from the Pampa plains to the south of Brazil.

We have started to identify the presence of FTPPs in southern Brazil and in some northern states, mostly by surface findings, like in other regions of South America some decades ago. The growing number of projectiles identified, their wide distribution in the landscape, the identification of preforms and the use, at least in some cases, of local raw materials, ensures the existence of these hunter-gatherers in parts of this territory, probably as one of the earliest human groups in southern Brazil, as it happened in the neighboring Pampa plains of Argentina and Uruguay. What we need to do now is to go forward by identifying the stratigraphic contexts of these early occupations. Such studies will also help clarify hypotheses concerning the local manufacturing and exchange of these points among groups located in the northern settings of Brazil.

The collection of FTPPs analyzed here shows designs and technological features similar to other regions from South America, demonstrating the continuity of human populations which shared information and technological behaviors during the colonization process of the subcontinent. We have observed the existence of a significant number of findings in southern Brazil, to which must be added those from the northern states. There is still an archaeological gap between these findings and those reported recently from Venezuela and Guyana, however, we can begin to draw a more complete record of the occupation of the Atlantic side of the humans who produced fishtail projectile points.

We would like to thank Astolfo Araujo (Centro Regional de Arqueologia Mario Neme, MAE-USP); Cláudia Inês Parellada (Museu Paranaense); Dione da Rocha Bandeira and Adriana Maria Pereira dos Santos (MASJ); Hugo Gemmer (Museu Municipal Pastor Karl Ramminger, Mondaí, SC); Igor Chmyz (CEPA, UFPR); Jefferson Dias (Marsul); Marisa Coutinho Afonso, Dária Barreto and Paulo Jacob (MAE-USP); Pedro Ignácio Schmitz (IAP, Unisinos); Sérgio Klamt (CEPA, UNISC); Tania Andrade Lima and Ângela Rabello (MN-UFRJ); Fabio Grossi dos Santos and Terezinha de Jesus Grombone (Museu Municipal de Jahu); and the private collectors. Hugo Nami, Alejandro Acosta, Romina Silvestre and Natacha Buc gave us valuable feedback. Regiane Eberts helped us with the images. Also we want to thank the good appreciations and suggestions we have received from the five reviewers. All the ideas and potential errors expressed herein are the sole responsibility of the authors. This research was funded by CNPq (grant numbers 159776/2010-4, 303566/2014-0, 443169/2014-9), FAPESP (grant no. 2010/06453-9), Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó-Unochapecó, Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica (PICT 2011-2035), Consejo Nacional de Investigations Científicas y Técnicas (PIP N° 11220110100565) and general support by the Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano. This project was also implemented with the support of the State of Santa Catarina, Department of Tourism, Culture and Sport, Santa Catarina Culture Foundation, FUNCULTURAL and Elisabete Anderle Grant, 2014.

do Amaral, S.E. 1971, Geologia e Petrologia da Formação Irati (Permiano) no Estado de São Paulo. Boletim do Instituto de Geociências e Astronomia da Universidade de São Paulo, 2: 3-81. (in Portuguese) (“Geology and Petrology of Irati Formation (Permian) from Sao Paulo State”). doi:10.11606/issn.2316-9001.v2i0p03-81

Baeza, J., & Femenías, J. 2005, Nuevos registros de puntas líticas “cola de pescado” de Uruguay. In: Libro de Resúmenes del Primer Encuentro de Discusión Arqueológica del noroeste Argentino, Santa Fé, p. 5-6. (in Spanish) (“New records of fishtail projectile points from Uruguay”)

Bell, R. 1960, Evidence of a fluted point tradition in Ecuador. American Antiquity, 26(1): 102-106. doi:10.2307/277167

Bell, R.E. 2000, Archaeological Investigation at the Site of El Inga, Ecuador. Monographs in Anthropology Vol. 1. University of Oklahoma, Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, Norman, Oklahoma, 94 p.

Becker, M. 1966, Quelques données nouvelles sur les sites préhistoriques de Río Claro, État de São Paulo. In: Actas y Memorias del XXXVI Congreso Internacional de Americanistas Vol. 1 (Jiménez Núñez, A., Ed.), ECESA, Seville: p. 445-450. (in French) ("Some new data on the prehistoric sites of Rio Claro, São Paulo state")

Beltrão, M.C. 1974. Datações arqueológicas mais antigas do Brasil. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 46(21): 211-251. (in Portuguese) (“Oldest archaeological datings from Brazil”)

Bettinger, R.L., & Eerkens, J.W. 1997, Evolutionary Implications of Metrical Variation in Great Basin Projectile Points. In: Rediscovering Darwin: Evolutionary Theory in Archeological Explanation (Barton, C. M., & Clark, G. A., Eds.), Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association Vol. 7, American Anthropological Association, Tulsa, Oklahoma: p. 177–191.

Bettinger, R.L., & Eerkens, J.W. 1999, Point typologies, cultural transmission, and the spread of bow-and-arrow technology in the prehistoric Great Basin. American Antiquity, 64: 231-242. doi:10.2307/2694276

Bird, J. 1938, Antiquity and migrations of the early inhabitants of Patagonia. Geographical Review, 28: 250-275. doi:10.2307/210474

Bird, J. 1969, A comparison of South Chilean and Ecuatorial “fishtail” projectile points. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, 40: 52-71.

Borrero, L. 1983, Distribuciones Discontinuas de Puntas de Proyectil en Sudamérica. In: 11th International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. Symposium Early Man in South America (Mayer-Oakes, W., Ed.), Vancouver: p.1-18. (in Spanish) (“Discontinued distributions of projectile points in South America”)

Borrero, L.A. 1994, Arqueología de la Patagonia. Palimpsesto, 4: 9-69. (in Spanish) (“Patagonian archaeology”)

Borrero, L. 2006, Paleoindians without Mammoths and Archaeologists without Projectile Points? The Archaeology of the First Inhabitants of the Americas. In: Paleoindian Archaeology: A Hemispheric Perspective (Morrow, J.E., & Gnecco, C., Eds.), University Press of Florida, Gainesville: p. 9-20.

Bosch, A., Femenías, J., & Olivera, A. 1980, Dispersión de las puntas líticas pisciformes en el Uruguay. In: Anales del III Congreso Nacional de Arqueología, CEA - Centro de Estudios Arqueológicos, Montevideo. (in Spanish) (“Dispersion of pisciform projectile points in Uruguay”)

Briceño Rosario, J.G. 2010, Las tradiciones liticas del Pleistoceno tardio en la quebrada Santa Maria, Costa Norte del Peru: Una contribucion al conocimiento de las puntas de proyectil paöeoindias cola de pescado. Doctoral thesis at the Department of History and Cultural Studies, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, 375 p. (in Spanish) ("The Lithic Tradition of the Late Pleistocene in the Quebrada Santa María, North Coast of Peru: A contribution to the knowledge of Paleo-Indian “fishtail” proyectile points"). URL: http://www.diss.fu-berlin.de/diss/receive/FUDISS_thesis_000000018239

Bueno, L., Schmidt Dias, A. & Steele, J. 2013, The Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene archaeological record in Brazil: A geo-referenced database. Quaternary International, 301: 74-93. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.03.042

Cambron, J.W., & Hulse, D.C. 2012, Handbook of Alabama Archaeology: Part I Point Types. The Archaeological Research Association of Alabama Inc. & Project Gutenberg, Retreived: 14 June 2015. URL: http://gutenberg.org/ebooks/39974

Castiñeira, C., Cardillo, M., Charlin, J., & Baeza, J. 2011, Análisis de morfometría geométrica en puntas cola de pescado del Uruguay. Latin American Antiquity, 22(3): 335-358. (in Spanish) (“Geometric morphometric analysis on fishtail points of Uruguay”) doi:10.7183/1045-6635.22.3.335

Chauchat, C., & Zevallos Quiñones, J. 1979, Una punta cola de pescado procedente de la costa norte de Perú. Ñawpa Pacha. Journal of Andean Archaeology, 17: 143-147. (in Spanish) (“A fishtail point from the northern coast of Peru”) doi:10.1179/naw.1979.17.1.007

Chiari, S. I. 2001, O Perfil Museo-Arqueológico do Projeto Paranapanema. Dissertação (Mestrado em Arqueologia), Master’s Thesis in Archaeology, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 201 p. (in Portuguese) (“The museological and archaeological profile of Paranapanema Project”)

Chmyz, I. 1978, Projeto Arqueológico Itaipu. Terceiro Relatório das Pesquisas Realizadas na Área de Itaipu (1977/78). Unpublished report IPHAN/Itaipu, Curitiba, 141 p. (in Portuguese) (“Itaipu Archaeological project. Third Report of research from Itaipu Area (1977/78)”)

Collet, G.C. 1980, Considerações sobre algumas peças líticas de “Pavão” (Itaoca, Apiaí, SP). Unpublished report Departamento de Arqueologia da SBE (Sociedade Brasileira de Espeleologia, São Paulo, 19 p. (in Portuguese) (“Considerations on some lithic pieces of "Pavão" site. Itaoca, Apiaí, SP”)

Collet, G.C. 1987, Descrição e algumas medidas referentes as pontas de projéteis de Itaoca. Temas, 2: 101-115. (in Portuguese) (“Description and some measures concerning the projectile points from Itaoca”)

Costa, F. 2009, Arqueologia das Campinaranas do baixo rio Negro: em busca dos pré-ceramistas nos areais da Amazônia Central. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, p. 181. (in Portuguese) (“Archaeology of Campinaranas at the lower Rio Negro: in search of pre-ceramist groups in the sands of Central Amazonia”). URL: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/71/71131/tde-29072009-145147/pt-br.php

Dias, A.S. 2012, Hunter-gatherer occupation of south Brazilian Atlantic Forest: Paleoenvironment and archaeology. Quaternary International, 256(4): 12-18. doi:10.1016/2011.08.024

Díaz Rodríguez, L.H. 2008, Una punta tipo “cola de pescado” con acanaladura de Quillane, Arequipa. Tambo. Boletín de Arqueología, 1: 73-82. (in Spanish) (“A "fishtail" projectile point with fluting from Quillane, Arequipa”)

Dillehay, T.D. 2000, The Settlement of the Americas: A New Prehistory. Basic Books, New York, 371 p.

Dillehay, T.D. 2012, Climate, technology and society during the terminal Pleistocene in South America. In: Hunter-Gatherer Behavior: Human Response During the Younger Dryas (Eren, M.I., Ed.), Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek: p. 25-55.

Eerkens, J.W., & Lipo, C.P. 2005, Cultural Transmission, Copying Errors, and the Generation of Variation in Material Culture and the Archaeological Record. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 24: 316-334. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2005.08.001

Eerkens, J.W., & Lipo, C.P. 2007, Cultural Transmission Theory and the Archaeological Record: Providing Context to Understanding Variation and Temporal Changes in Material Culture. Journal of Archaeological Research, 15(3): 239-274. doi:10.1007/s10814-007-9013-z

Eugenio, E. 1983, Una punta “Cola de Pescado” de Lobos, Provincia de Buenos Aires. ADEHA, 2: 20-31. (in Spanish) (“A "fishtail" point from Lobos, Buenos Aires province”)

Femenías, J., Nami, H.G., Florines, A., & Toscano, A. 2011, GIS archaeological site record and remarks on paleoindian finds in the Rio Negro River Basin, Central Uruguay. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 28: 98-101.

Flenniken, J.J., & Raymond, A.W. 1986, Morphological Projectile Point Typology: Replication, Experimentation, and Technological Analysis. American Antiquity, 51(3): 603-614. doi:10.2307/281755

Figueira, J.H. 1892, Los primitivos habitantes del Uruguay. In: El Uruguay en la Exposición Histórica Americana de Madrid (Figueira, J.H. & Dornaleche, R., Eds.), Imprenta Artística Americana, Montevideo: p. 121-219. (in Spanish) (“The original inhabitants of Uruguay”)

Flegenheimer, N. Martínez, J.G., & Colombo, M. 2010, Un experimento de lanzamiento de puntas cola de pescado. In: Mamül Mapu. Pasado y Presente desde la Arqueología Pampeana II (Berón, M., Luna, L., Bonomo, M., Monsalvo, C., Aranda, C., & Carrera Aizpitarte, M., Eds.), Libros del Espinillo, Ayacucho: p. 215-232. (in Spanish) (“Launch experiment of fishtail points”)

Flegenheimer, N., Miotti L., & Mazzia, N. 2013, Rethinking early objects and landscape in the Southern Cone: Fishtail point concentrations in the Pampas and Northern Patagonia. In: Paleoamerican Odyssey Conference Companion Book (Graf, K., Ketron, C., & Waters, M., Eds.), Texas A. & M. University Press, College Station: p. 359-376.

Grosjean, M., Núñez, L., & Cartagena, I. 2005, Palaeoindian occupation of the Atacama desert, Northern Chile. Journal of Quaternary Science, 20: 643-654. doi:10.1002/jqs.969

Hermo, D., & Terranova, E. 2012, Formal variability in Fishtail Projectile Points of Amigo Oeste archaeological site, Plateau (Río Negro, Argentina). In: Southbound, the Late Pleistocene Peopling of Latin America (Miotti, L., Salemme, M., Flegenheimer, N., & Goebel, T., Eds.), Center for the Study of the First Americans, Texas A. & M. University Press, College Station: p. 121–26.

Jackson, D., Méndez, C., Seguel, R., Maldonado, A., & Vargas, G. 2007, Initial occupation of the Pacific coast of Chile during Late Pleistocene times. Current Anthropology, 48(5): 725-731. doi:10.1086/520965

Laguens, A.G., Pautassi, E.A., Sario, G.M., & Cattaneo, G.R. 2007, ELS1, a fishtail projectile-point site from Central Argentina. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 24: 55–57.

León Canales, E. 2007, Orígenes humanos en los Andes del Perú. Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima, 328 p. (in Spanish) (“Human origins in the Andes of Peru”)

Loponte, D., Carbonera, M., & Sivestre, R. 2015, Fishtail Projectile Points from South America: The Brazilian Record. Archaeological Discovery, 3(3): 1-19. doi:10.4236/ad.2015.33009

Maggard, G.J. 2015, The El Palto Phase Of Northern Perú: Cultural Diversity In The Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene. Chungará, 47(1): 25-40. doi:10.4067/S0717-73562015005000009

Maggard, G.J., & Dillehay, T.D. 2011, El Palto Phase (13,800-9800 BP). In: From Foraging to Farming in the Andes: New Perspectives on Food Production and Social Organization (Dillehay, T.D., Ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: p. 77-94,

Martínez, G. 2001, “Fish-tail” projectile points and megamammals: New evidence from Paso Otero 5 (Argentina). Antiquity, 75: 523-528. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0008873

Mayer-Oakes, W. 1963, Early man in the Andes. Scientific American, 208: 117-128. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0563-116

Mayer-Oakes, W. 1986, El Inga. A paleoindian site in the sierra of northern Ecuador. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 76: 1-335.

Mazzanti, D. 1999, El sitio Abrigo Los Pinos: Arqueología de la ocupación Paleoindia, Tandilia Oriental, Provincia de Buenos Aires. In: Actas del XII Congreso Nacional de Arqueología Argentina. Vol. 3. (Diez Marín, C., Ed.), Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata: p. 145-148. (in Spanish) (“Shelter Los Pinos site: Archaeology of the Paleoindian occupation, Eastern Tandilia, Buenos Aires province”)

Mazzanti, D. 2002, Secuencia arqueológica del sitio 2 de la localidad arqueológica Amalia (Provincia de Buenos Aires). In: Del Mar a los Salitrales: Diez mil años de historia pampeana en el umbral del tercer milenio (Mazzanti D., Berón M., & Oliva F., Eds.), Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Mar del Plata: p. 327-339. (in Spanish) (“Archaeological sequence of site 2 at Amalia archaeological area, Buenos Aires Province”)

Mazzanti, D. 2003, Human settlements in caves and rockshelters during the Pleistocene and Holocene transition in the Eastern Tandilia Range, Pampean Region, Argentina. In: From Where the South Winds Blows: Ancient Evidence for Paleo South Americans (Miotti, L., Salemme, M., Flegenheimer, N., Eds.), Texas A. & M. University Press, College Station: p. 57-61.

Meggers, B. 2007, Mid-Holocene climate and cultural dynamics in Brazil and the Guianas. In: Climate Change and Cultural Dynamics. A Global Perspective on Mid-Holocene Transitions (Anderson, D.G., Maasch, K.A., & Sandweiss, D.H., Eds.), Elsevier, Salt Lake City: p. 117-155.

Meltzer, D.J. 1989, Was Stone Exchanged among Eastern North American Paleoindians? In: Eastern Paleoindian Lithic Resource Use (Ellis, C. & Lothrop, M., Eds.), Westview Press, Boulder: p. 11- 39.

Meneghin, U. 2004, URUPEZ. Primer registro radiocarbónico (C-14) para un yacimiento con puntas líticas pisciformes del Uruguay Orígenes, 2: 1-30. (in Spanish) (“First radiocarbon (C-14) record for a site presenting pisciform projectile points from Uruguay”)

Meneghin, U. 2006, Un nuevo registro radiocarbónico (C-14) en el Yacimiento Urupez II, Maldonado, Uruguay. Orígenes, 5; 1-7. (in Spanish) (“A new radiocarbon (C-14) record from Urupez II site”)

Miller, E.T. 1969, Resultados preliminares das escavações no sítio pré-cerâmico RS-LN-1: Cerrito Dalpiaz (abrigo-sob-rocha). Iheringia, Antropologia, 1: 43-112. (in Portuguese) (“Preliminary results of the excavations in the pre-ceramic site RS-LN-1: Cerrito Dalpiaz, rockshelter”)

Miller, E.T. 1987, Pesquisas arqueológicas paleoindígenas no Brasil Ocidental. Estudios Atacameños, 8: 39-64. (in Portuguese) (“Paleoindian archaeological research in Western Brazil”)

Miotti, L., & Salemme, M. 2005, Hunting and butchering events at Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene in Piedra Museo (Patagonia, Southermost South America). In: Paleoamerican Prehistory: Colonization Models, Biological populations, and Human Adaptations (Bonnichsen, R., Ed.), Center for the Study of the First Americans, Texas A. & M. University, College Station: p.141–151.

Miotti, L., Hermo, D., & Terranova, E. 2010, Fishtail points, First evidence of late-Pleistocenic hunter-gatherers in Somuncurá plateau (Rio Negro province, Argentina). Current Research in the Pleistocene, 27: 22–24.

Mujica, J. 1995, Puntas cola de pescado de la costa occidental del río Uruguay medio, litoral argentino. Comechingonia, Revista de Arqueología, 8: 199-207. (in Spanish) (“Fishtail points of the western coast of Middle River Uruguay, Argentine fluvial coast”)

Nami, H.G. 1987, Cueva del Medio: Perspectivas arqueológicas para la Patagonia Austral. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia, 17: 71-106. (in Spanish) (“Cueva del Medio: Archaeological perspectives for Southern Patagonia Austral”)

Nami, H.G. 1990, Observaciones sobre algunos artefactos bifaciales de Bahía Laredo. Consideraciones tecnológicas para el extremo austral. Anales del Instituto de la Patagonia, 19 (1989-1990): 141-151. (in Spanish) (“Comments on some bifacial artifacts of Laredo Bay. Technological considerations for the southern extreme”)

Nami, H.G. 1992, Nuevos datos en relación a las puntas de proyectil paleoindias encontradas en el Cono Sur (Neuquén, Argentina). Palimpsesto. Revista de Arqueología, 1: 71-74. (in Spanish) (“New data regarding Paleoindian projectile points found in the Southern Cone, Neuquén, Argentina”)

Nami, H.G. 1998, Technological observations on the Paleoindian artifacts from Fell's cave, Magallanes, Chile. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 15: 81-83.

Nami, H.G. 2000, Technological Comments of some Paleoindian Lithic Artifacts from Ilaló, Ecuador. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 17: 104-107.

Nami, H.G. 2001, Consideraciones tecnológicas preliminares sobre los artefactos líticos de Cerro de los Burros (Maldonado, Uruguay). Comunicaciones Antropológicas, 21(III): 1-23. (in Spanish) (“Preliminary technological considerations about lithic artifacts from Cerro de los Burros (Maldonado, Uruguay”)

Nami, H.G. 2003, Experimentos para explorar la secuencia de reducción Fell de la Patagonia Austral. Magallania, 31: 107-138. (in Spanish) (“Experiments to explore the sequence of Fell reduction of Patagonia”)

Nami, H.G. 2007, Research in the middle Negro River basin (Uruguay) and the Paleoindian occupation of the Southern cone. Current Anthropology, 48(1): 164-176. doi:10.1086/510465

Nami, H.G. 2009, Crystal quartz and fishtail projectile points: Considerations on raw materials selection by Paleo-South Americans. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 26: 9-12.

Nami, H.G. 2010, Tecnología paleoindia de Sudamérica: Nuevos experimentos y observaciones para conocer la secuencia de reducción Fell. Orígenes, 9: 1-40. (in Spanish) (“Paleoindian Technology in South America: New experiments and observations to determine the sequence of Fell reduction”)

Nami, H.G. 2011a, Observaciones experimentales sobre las puntas de proyectil Fell de Sudamerica. In: La Investigación Experimental Aplicada a la Arqueología (Morgado, A., Baena Preysler, J., & García González, D., Eds.), Ronda: Universidad de Granada-Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid: p. 105-111. (in Spanish) (“Experimental observations on Fell projectile points from South America”)

Nami, H.G. 2011b, Exceptional Fell projectile points from Uruguay: More data on Paleoindian technology in the southern cone. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 28: 112-116.

Nami, H.G. 2013, Archaelogy, paleoindian research and lithic technology in the Middle Negro River, Central Uruguay. Archaeological Discovery, 1: 1-22. doi:10.4236/ad.2013.11001

Nami, H.G. 2014a, Arqueología del último milenio del Pleistoceno en el Cono Sur de Sudamérica, puntas de proyectil y observaciones sobre tecnología Paleoindia en el Nuevo Mundo. In: Peuplement et modalités d’occupation de l’Amérique du sud: l’apport de la technologie lithique (Farias, M., & Lourdeau, A., Eds.), @rchéo-éditions.com, Prigonrieux: p. 279-336. (in Spanish) (“Archaeology of the last millennium of the Pleistocene in the Southern Cone of South America, projectile points and observations on Paleoindian technology in the New World”)

Nami, H.G. 2014b, Observaciones para conocer secuencias de reducción bifaciales paleoindias y puntas Fell en el valle del Ilalo, Ecuador. In: Peuplement et modalités d’occupation de l’Amérique du sud: l’apport de la technologie lithique (Farias, M., & Lourdeau, A., Eds.), @rchéo-éditions.com, Prigonrieux: p. 179-220. (in Spanish) (“Observations to learn sequences of Paleoindian bifacial reduction and Fell points in the valley of Ilalo, Ecuador”)

Nami, H.G. 2015a, Experimental Observations on some non-optimal materials from Southern South America. Lithic Technology, 40(2): 128-146. doi:10.1179/2051618515Y.0000000004

Nami, H.G. 2015b, New Records and Observations on Paleo-American Artifacts from Cerro Largo, Northeastern Uruguay and a Peculiar Case of Reclaimed Fishtail Points. Archaeological Discovery, 3: 114-127. doi:10.4236/ad.2015.33011

Nami, H.G. 2015c, Paleoamerican Artifacts from Cerro Largo, Northeastern Uruguay. PaleoAmerica, 1: 288-292. doi:10.1179/2055557115Y.0000000005

Nami, H.G., & Heusser, C.J. 2015, Cueva del Medio: A Paleoindian Site and Its Environmental Setting in Southern South America. Archaeological Discovery, 3: 62-71. doi:10.4236/ad.2015.32007

Nelson, M.C. 1991, The study of technological organization. Archaeological Method and Theory, 3: 57-100. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20170213

Núñez, L., Casamiquela, R., Schiappacasse, V., Niemeyer, H., & Villagrán, C. 1994, Cuenca de Taguatagua en Chile: El ambiente del Pleistoceno y ocupaciones humanas. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 67: 503-519. (in Spanish) (“Taguatagua basin in Chile: The Pleistocene environment and human occupation”). URL: http://rchn.biologiachile.cl/pdfs/1994/4/Nu%C3%B1ez_et_al_1994.pdf

do Nascimento, M. M. 2010, Pedra que te quero palavra: discursividade e semiose no (con)texto arqueológico da Tradição Itaparica. Ph.D. thesis. Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre. 195 p. (in Portuguese) (“Stone that I want to become word: discourse and semiosis in archaeological (con) text of Itaparica Tradition”) URL: http://repositorio.pucrs.br/dspace/handle/10923/3759

O’Brien, M.J., & Lyman, R.L. 2003a, Style, Function, Transmission. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. 352 p.

O’Brien, M.J., & Lyman, R.L. 2003b, Cladistics and Archaeology. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City. 304 p.

O’Brien, M.J., Lyman, R.L., Collard, M., Holden, C.J., Gray, R.D., & Shennan, S.J. 2008, Transmission, Phylogenetics, and the Evolution of Cultural Diversity. In: Cultural Transmission and Archaeology: Issues and Case Studies (O’Brien, M.J., Ed.), Society for American Archaeology Press, Washington, D.C.: p. 39-58.

Okumura, M., & Araujo, A.G.M. 2013, Pontas Bifaciais no Brasil Meridional: Caracterização Estatística das Formas e suas Implicações Culturais. Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia, 23: 111-127. (in Portuguese) (“Bifacial points in Southern Brazil: Statistics characterization of Forms and its Cultural Implications”)

Okumura, M., & Araujo, A.G.M. 2014, Long-term cultural stability in hunter and gatherers: a case study using traditional and geometric morphometric analysis of lithic stemmed bifacial points from Southern Brazil. Journal of Archaeological Science, 45: 59-71. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.02.009

Oliveira, O.A. 2014, Os povos caçadores e coletores que habitaram as margens da Lagoa Mirim. Ph. D. Thesis, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos – Unisinos, São Leopoldo, 144 p. (in Portuguese) (“Hunters and gatherers who inhabited the shores of the Lagoa Mirim”)

Patané Aráoz, C., & Nami, H.G. 2014, The first Paleoindian fishtail point find in Salta Province, Northwestern Argentina. Archaeological Discovery, 2: 26-30. doi:10.4236/ad.2014.22004

Politis, G. 1991, Fishtail Projectile Points in the Southern Cone of South America: An Overview. In: Clovis: Origins and Adaptations. (Bonnichsen, R., & Turnmire, K., Eds.), Oregon State University, Corvallis: p. 287-301.

Prous, A. 1992, Arqueologia Brasileira. Universidade de Brasília, Brasília. 605 p. (in Portuguese) (“Brazilian Archaeology”)

Prous, A., & Fogaça, E. 1999, Archaeology of the Pleistocene-Holocene boundary in Brazil. Quaternary International, 53/54: 21-41. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(98)00005-6

Rapp, G.R. 2002, Archaeomineralogy (Natural Science in Archaeology Series). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 326 p.

Rohr, J.A. 1966, Pesquisas arqueológicas em Santa Catarina, os sítios arqueológicos do município de Itapiranga. Pesquisas: Antropologia, 15: 21-60. (in Portuguese) (“Archaeological research in Santa Catarina, the archaeological sites of Itapiranga County”)

Schobinger, J. 1969, Prehistoria de Suramérica. Editorial Labor, Barcelona. 300 p. (in Spanish) (“Prehistory of South America”)

Schobinger, J. 1971, Una punta de tipo “cola de pescado” de La Crucesita (Mendoza). Anales de Arqueología y Etnología, 26: 89-97. (in Spanish) (“A “fishtail” point from La Crucesita, Mendoza”)

Schobinger, J. 1974, Nuevos hallazgos de puntas “cola de pescado” y consideraciones en torno al origen y dispersión de la cultura de Cazadores Superiores Toldense en Sudamérica. Atti del XL Congresso Internazionale degli Americanisti, 1: 33-50. (in Spanish) (“New findings of "fishtail" points and considerations about the origin and spread of the culture of Toldense specialized hunters in South America”)

Serrano, A. 1932, Exploraciones Arqueológicas en el río Uruguay Medio. Memorias del Museo de Paraná, 2: 1-89. (in Spanish) (“Archaeological exploration in the Middle Uruguay River”)

Shennan, S.J. 2002, Genes, Memes and Human History. Thames and Hudson, London. 304 p.

Silva Lopes, L., & Nami, H.G. 2011. A New Fishtail Point Find from South Brazil. Current Research in the Pleistocene, 28: 104-107.

Stevaux, J.C., Souza-Filho, E.E., & Fúlfaro, V.J. 1986, Trato deposicional da Formação Tatuí (P) na área aflorante do NE da Bacia do Paraná, Estado de São Paulo. Anais XXXIV Congresso Brasileiro de Geologia, Goiânia. Sociedade Brasileira de Geologia, 1: 219-229. (in Portuguese) (“Depositional Tract from Tatuí Formation (SP) in the northwest outcropping area of the Paraná Basin, State of Sao Paulo”)

Suárez, R. 2004, Arqueología de los Primeros Americanos en Uruguay: Componentes Paleoindios de los Ríos Uruguay-Cuareim y Asociación entre Cazadores Humanos y Fauna Pleistocénica en el sitio Pay Paso 1. In: X Congreso Uruguayo de Arqueología: La Arqueología Uruguaya ante los desafíos del nuevo siglo (Beovide, L., Barreto, I., & Curbelo, C., Eds.), CD-ROM Multimedia, Montevideo, p: 0-41 (in Spanish) (“Archaeology of the First Americans in Uruguay: Paleoindian components at the Uruguay-Cuareim Rivers and the association between human hunters and Pleistocene fauna at the site Pay Paso 1”)

Suárez, R. 2015, The Paleoamerican Occupation of the Plains of Uruguay: Technology, Adaptations, and Mobility. PaleoAmerica, 1(1): 88-104. doi:10.1179/2055556314Z.00000000010

Wildner, W., Brito, R.S.C., & Licht, O.A.B. 2006, Geologia e Recursos Minerais do Estado do Paraná. Convênio CPRM/MINEROPAR. Brasília, 35 p. (in Portuguese) (“Geology and Mineral Resources of the Paraná State”), Retrieved: 15 June 2015. URL: http://www.mineropar.pr.gov.br/arquivos/File/mapeamento/Geologia_e_Recursos_Minerais_Sudoeste_do_PR2006.pdf